By Cameron Macht

December 2020

Suffice it to say, 2020 has not been like anyone expected at its outset – economically or otherwise. As the coronavirus spread across the state, almost every aspect of normal life has been affected: schools changed to distance learning; sports seasons, weddings, and surgeries were all postponed; telework skyrocketed; health care systems both shut down some activities and ramped up others to prepare for and deal with the pandemic; and record numbers of jobs were lost across many industries. This article examines what has happened in Minnesota’s economy in 2020 and what could have been if the pandemic hadn’t dramatically changed the labor market landscape.

Through February, Minnesota was in the midst of the longest running economic expansion on record, still growing through the first quarter of the year. But instead of continuing to hit new record heights, constrained only by a slowing labor force growth rate, our economy instead suffered record job losses in the second quarter. The state lost over 330,000 jobs from March to April, an 11.4% drop. Through October, the state is still down nearly 190,000 jobs compared to the same month in 2019, but had recovered over 250,000 jobs that were lost from March to April.

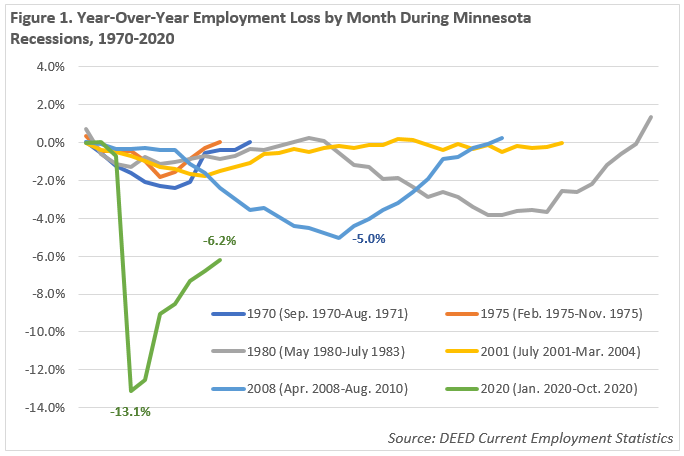

In the span of two months between March and May 2020, our state went from a tight labor market where job vacancies outnumbered job seekers to a historically high unemployment rate. Though overused, the word “unprecedented” best describes the speed and scope of the COVID-19 recession (see Figure 1).

Typically, much like the weather, Minnesota’s economy starts to heat up moving from the first quarter to the second quarter of each year. Our seasonal economy welcomes in new jobs as employers from restaurant owners to landscapers increase staffing for the busy summer season. Through the first quarter of 2020, we were up almost 10,000 jobs compared to the first quarter of 2019, seemingly on pace for new record high job numbers.

Most notably, summer months normally include big gains in Construction. In 2019, the industry built up payrolls by more than 23,600 jobs from the first to the second quarter, a 20.7% increase; making it both the largest and fastest growing industry in the state from winter to summer. With sustained economic activity creating commercial and industrial demand and a booming residential real estate market, Construction had nearly regained employment levels not seen since right before the Great Recession.

The second biggest job gainer is usually Accommodation & Food Services, which added 13,440 jobs from quarter one to quarter two last year, a 6.0% increase. With nearly 224,000 jobs in the first quarter of 2020, industry employment was already near historic highs. Likewise, at 48,575 jobs, the related Arts, Entertainment and Recreation industry was within 75 jobs of its highest first quarter job count on record, set in 2019. Last year, it was the fourth largest and third fastest growing industry from quarter one to quarter two, adding nearly 7,000 jobs, a 14.1% increase.

The Administrative and Support and Waste Management Services industry, which includes both temporary staffing agencies as well as services to buildings and dwellings including landscaping, also typically ramps up hiring in the summer. These employers added just under 7,000 jobs in 2019, a 5.4% increase. Seasonal demand also leads to rapidly growing hiring activity in Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing & Hunting, which popped up 15.4% in 2019, and a 12.2% expansion in Mining. Only one industry, Educational Services, saw a dip in employment from the first to the second quarter of 2019, which makes sense as students and teachers normally get the summer off.

However, as noted, this year was unlike any other. Instead of adding jobs from the first quarter to the second quarter, the coronavirus pandemic caused the entire country to restrict some business activities, and Minnesota was no exception. Various measures were enacted via executive order over the course of the spring, summer and into the fall to help slow the spread of the virus and to protect workers, customers and our healthcare system.

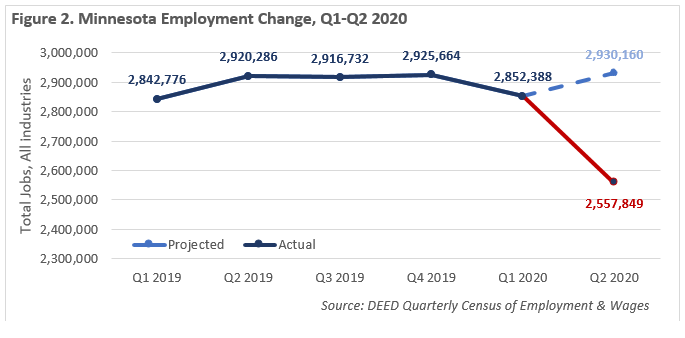

Under normal circumstances, Minnesota’s economy would have been expected to continue growing, though at a slower rate due to the tight labor market. Based on last year’s trends, employers would have likely reported well over 75,000 additional jobs from quarter one to quarter two; again putting us about 10,000 jobs ahead of last year’s levels. Instead, the state cut nearly 295,000 jobs from quarter one to quarter two, a 10.3% decline. That puts us almost 375,000 jobs below where we could have been (see Figure 2).

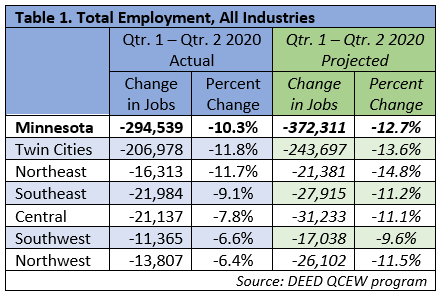

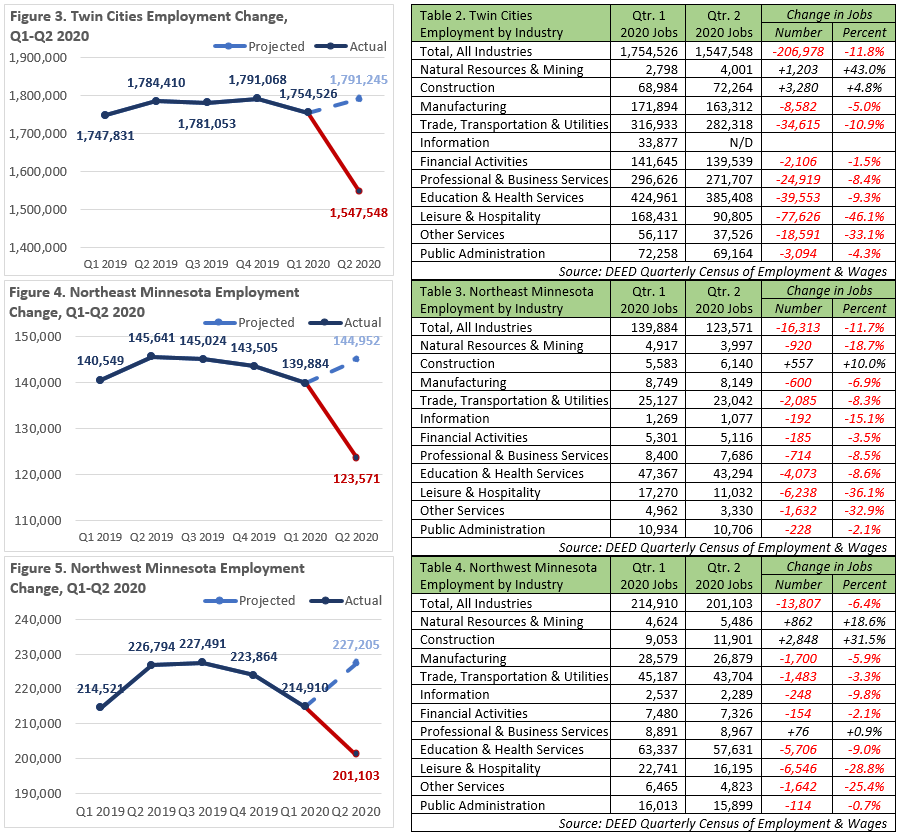

The job losses were concentrated in the 7-county Twin Cities metro area, which accounted for over 70% of the state’s total employment decline from first to second quarter 2020 (see Table 1). The Twin Cities lost more than 60,000 jobs in Accommodation and Food Services, and around 25,000 jobs apiece in both Health Care and Social Assistance and Retail Trade. The metro also suffered massive cuts in Arts, Entertainment and Recreation, Other Services, and Administrative Support and Waste Management Services (see Table 2 and Figure 3).

Due to a heavier reliance on customer-facing and more seasonal industries like Accommodation and Food Services, Arts, Entertainment and Recreation and Other Services, which all declined more than 33%, Northeast Minnesota was also worse off than other parts of the state, especially when compared to where they would normally be (see Table 3 and Figure 4). In contrast, Southwest and Northwest, which rely more on agriculture and manufacturing, saw the smallest declines from quarter one to quarter two.

Despite an immediate surge in unemployment insurance claims, Northwest Minnesota saw much smaller declines in the leisure and hospitality industries, as well as bigger increases in Construction, Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting, and was the only region to see job gains in Administrative Support and Waste Management. However, Northwest typically has a much bigger seasonal bump in employment, and they are still well below where they would normally be (see Table 4 and Figure 5).

Southwest also benefited from better results in Construction, Agriculture, and Wholesale Trade (particularly in farm supplies and products), though those gains were offset by losses in Accommodation and Food Services, Other Services, and Real Estate, Rental and Leasing. Of the six regions, Southwest saw the smallest declines in Arts, Entertainment and Recreation and Health Care and Social Assistance (see Table 5 and Figure 6).

In contrast, slashes to Southeast Minnesota’s highly concentrated Health Care and Social Assistance industry accounted for the largest share of total job loss of any of the six regions, accounting for more than 4,000 of the region’s 22,000 job cuts. Accommodation and Food Services sliced just over 7,000 jobs, a 36% decline, topped only by Arts, Entertainment and Recreation, which fell 40% (see Table 6 and Figure 7).

Central benefited from a strong start to the Construction season and a growing Agriculture industry, but couldn’t overcome the loss of nearly 8,250 jobs in Accommodation and Food Services and around 3,000 fewer jobs in Health Care and Social Assistance, Educational Services, and Retail Trade (see Table 7 and Figure 8).

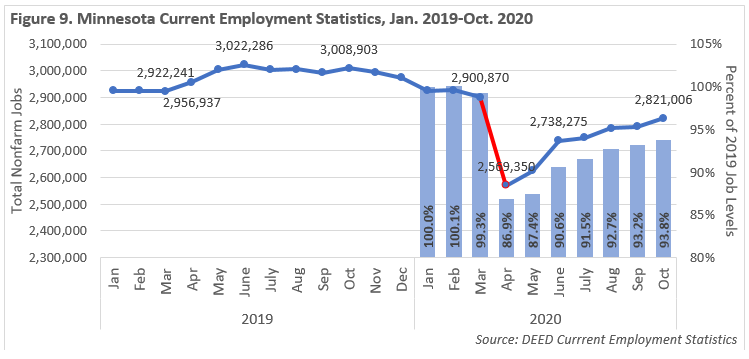

Though third quarter data from QCEW won’t be available until early in 2021, data from DEED’s Current Employment Statistics (CES) program shows that the state was already making progress toward regaining many of the jobs it lost from the first to the second quarter. CES data, not seasonally adjusted, revealed that Minnesota cut 331,520 jobs from March to April. Then by May, the state started regaining lost jobs quickly, adding just over 56,000 jobs from April to May, then doubling that to 112,700 additional jobs from May to June.

Job recovery slowed going into the fall, partly due to falling labor force participation rates, averaging about 21,000 additional jobs over the past 4 months in a more uneven recovery. However, it also means the state has gained back just over 75% of the jobs it lost at the outset of the pandemic recession, not seasonally adjusted (see Figure 9).

As noted at the beginning, Minnesota’s employment was up 0.1% in February year over year, but by March it was down 0.7% compared to 2019. Everything changed by April – Minnesota was down 13.1% over the year, the largest drop in the history of the CES program. The small gain in May left us down 12.6% compared to May of 2019. In 2019, April and May saw the largest month-over-month job gains; this year they saw the largest decline in the history of the program.

Many lives were interrupted in challenging and tragic ways as the coronavirus spread across the state and the nation. Many industries lost jobs during the time of year when they typically would have been adding jobs. But businesses quickly adapted to the new normal, and the state regained many of the jobs lost over the course of the summer. Still, the road to recovery is expected to be long and winding, with uneven recovery across industry sectors and complicated by the ongoing uncertainty of the path of the coronavirus pandemic. Forecasts show that it may take well into 2022 or even 2023 to fully regain all of the jobs lost in this pandemic-induced recession, not to mention the jobs that could have been added over that period.