by Dave Senf

August 2021

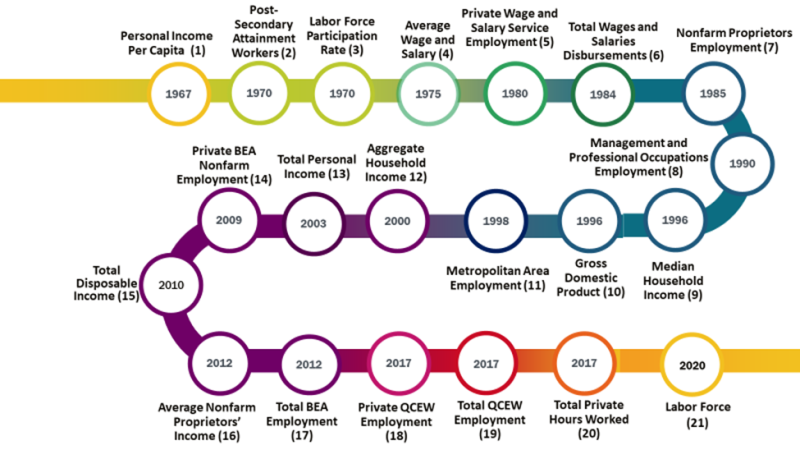

Most Minnesotans and Wisconsinites know all about Viking and Packer clashes and Gopher and Badger skirmishes in various college sports. No score updates or deep analysis of the various Minnesota -Wisconsin sporting rivalries is offered here. Instead, a historical timeline that traces the Minnesota and Wisconsin economic border battle through the years is presented. There are no runs, goals, or touchdowns reported, only milestones of Minnesota bettering Wisconsin for the first time on various key economic statistics. The timeline may appear somewhat biased towards the Gopher state, but the economic measurements displayed are among the most widely used to evaluate the economic success and health of states.1 Indicators such as personal income per capita, Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and median household income are widely used economic parameters used to compare and evaluate countries, states, and regional economics.

An extensive amount of literature exploring why certain U.S. states and other regional areas, like metropolitan areas, experience greater rates of income and employment growth than other places exist. In fact, there is a whole field of economics, regional economics, devoted to the topic. Here is a partial list of the numerous factors that have been commonly cited as determinants of differences in state or metro area economic growth. No attempt is made here to analyze statistically the various factors and come up with a definitive answer to the importance of one factor over another factor. Instead, readers are invited to argue the merits of the various factors just as they argue the pluses and minuses of the Viking and Packer football teams. The milestones, however, provide a long-term scoreboard of the Minnesota and Wisconsin economic border battle. The scoreboard indicates that over the last four decades Minnesota appears to have gained a slight upper hand.

In 1970 Wisconsin had a population of 4.4 million or 16% more people than Minnesota's population of 3.8 million. Wisconsin's GDP in 1970 was $20.2 billion (in 1970 dollars) or 8% larger than Minnesota's $18.7 billion GDP. Employment in Wisconsin 50 years ago was 1.9 million or 14.9% more than 1.7 million employment in Minnesota. Flash ahead to 2020, and Wisconsin still has a more residents than Minnesota with Wisconsin's population topping Minnesota population by 2.3%, 5.9 to 5.7 million residents.2 Minnesota's employment, however, topped Wisconsin employment in 2020 as measured by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), 3.56 to 3.34 million. Minnesota workers produced more goods and services, $328.5 billion GPD (in 2020 dollars) or 11.7% more than Wisconsin workers.3

Over the last five decades the Minnesota economy has gradually grown larger than Wisconsin's economy by most widely used economic barometers. Minnesota's economy has surpassed Wisconsin's whether measured by GDP, personal income, total employment, private employment, nonfarm proprietors' employment, personal income, disposable personal income, aggregate household income, or labor force size.

Minnesota's economy has not only surpassed Wisconsin's in size but more importantly in economic measurements that indicate a higher standard of living in Minnesota than Wisconsin. Per capita income in Minnesota is higher than in Wisconsin as is per capita disposable income, median household income, and per capita personal consumption expenditures.4 Personal consumption expenditure, better known as consumer spending, measures how consumers spend their money on goods and services. Per capita personal consumption expenditures were estimated to be 9.3% higher in Minnesota ($47,155) than in Wisconsin ($43,152) in 2019.

Each state obviously has unique attributes and challenges, but it is safe to say that there are more similarities than differences between Minnesota and Wisconsin. This is especially so when it comes to many of the possible determinants of long-term economic growth listed above. Until recently it was hard to detect much difference in labor laws, state and local tax burdens, state and local spending, economic freedom, quality of life, and unionization rates. The differences between the two states in human capital, industry mix, population density, and product life cycle on the other hand may be the driving forces behind Minnesota's gradual gain in the economic border battle. Higher educational attainment in Minnesota allowed for the growth of industries that employed higher-paying management and professional occupations.

These industries have grown faster than goods producing industries like manufacturing and agriculture. Much of the growth has occurred in the Twin Cities area, giving rise to agglomeration effects which refers to the economic benefits that come when firms locate near each other and the consumer base expands. The forces of agglomeration contribute to the formation of industry clusters which reinforce economic growth. The main-frame computer cluster in the 70s and 80s in Minnesota is a prime example of agglomeration benefits leading to higher economic growth. In 1970 the Twin Cities metro area had a population that was 45% percent bigger than the Milwaukee metro area. The Twin Cities area population was 130% bigger than Milwaukee metro area in 2020.

Will Minnesota's gradual economic growth rate continue to exceed its neighboring state to the east? Forces that drive economic growth continually shift over time increasing (decreasing) one state's economic advantage over another state. Thinking about how the possible determinants of state growth listed above may change quickly in the future raises multiple scenarios covering possible paths of economic growth in Minnesota and Wisconsin. Not listed above is the largest factor, at least over the next few years, and that factor is how has and will the pandemic impact the two state economies?

Will there be a permanent increase in remote work that will lessen the roll of urban downtowns? Does that mean that Minnesota will lose some of the agglomeration benefits generated in the Twin Cities? Will supply chain disruptions that arose during the pandemic lead to significant reshoring of manufacturing activity that could benefit the more manufacturing-dependent Wisconsin than Minnesota? What about expanding medical research stimulated by the pandemic? Will the increase in research spending spur additional healthcare employment growth in the Rochester medical research cluster or at the University of Minnesota or University of Wisconsin? If you have all the answers to how the pandemic will ultimately alter the two states' economies, perhaps then you can move on and answer how global climate change and public and private sector responses to climate change will impact the economic growth of Minnesota and Wisconsin over the next 50 years. The score board provided above is just the halftime report and shows Minnesota with a slight lead.

1Milestone data sources and links are provided at the end of the article in Table 1.

22020 U.S. Census.

3Population, GDP, and employment data are from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

4Per capita personal consumption numbers are for 2019 and from BEA data.