by Oriane Casale, Zina Noel, and Suzanne Pearl

September 2020

Even before COVID-19, the early care and education industry, critical to Minnesota’s workers and employers, had been experiencing a quiet crisis. While the cost of care is high, pay, even for professional positions, is below that of other occupations with similar qualifications and many positions pay below the basic cost of living in the communities in which these programs operate. These low wages do not provide staff the financial resources or incentives to obtain credentials and move up career ladders that offer little or no pay increase. As a result, programs struggle to find and keep qualified staff to meet basic licensing requirements even as parents struggle to cover the costs.

Prior to the impacts of COVID-19, Minnesota was short nearly 80,000 child care slots. The need for more child care availability is particularly acute in Greater Minnesota where the numbers of child care centers are not increasing at the same rate as in the metro and family child care provider capacity has declined dramatically between 2006 and 2015. (see A quiet crisis: Minnesota’s child care shortage, Center for Rural Policy and Development, September 2016).

These problems compromise the quality of care for young children who benefit from well-trained and consistent caregivers and high-quality learning environments. Rob Grunewald, an economist with the Minneapolis Federal Reserve, makes the case that high-quality care often costs more than parents can pay, resulting in underinvestment in our young children. Moreover, research shows that children who experience the greatest gains from a quality, stable child care environment – lower income children, children of color and indigenous children - are in families that face the greatest barriers to affording and accessing that care. This underinvestment, in turn, compromises the ability of parents with young children to fully participate in the labor market and the ability of businesses to hire and retain these workers. Simultaneously, it results in missed opportunities to ensure our future workforce has the chance early in their lives that help them thrive in the future.

In the United States, parents bear a significant burden for the cost of early care and education. In fact, parents pay for about 52% of the costs of this very labor-intensive industry, while federal and state government, public school systems and foundations cover the rest. The financial burden on parents generally comes at the beginning or middle point of parents’ careers when earnings are lower than they may be once workers gain experience and have time to move up in their career. The financial burden is much more onerous for single-parent families and low-income families.

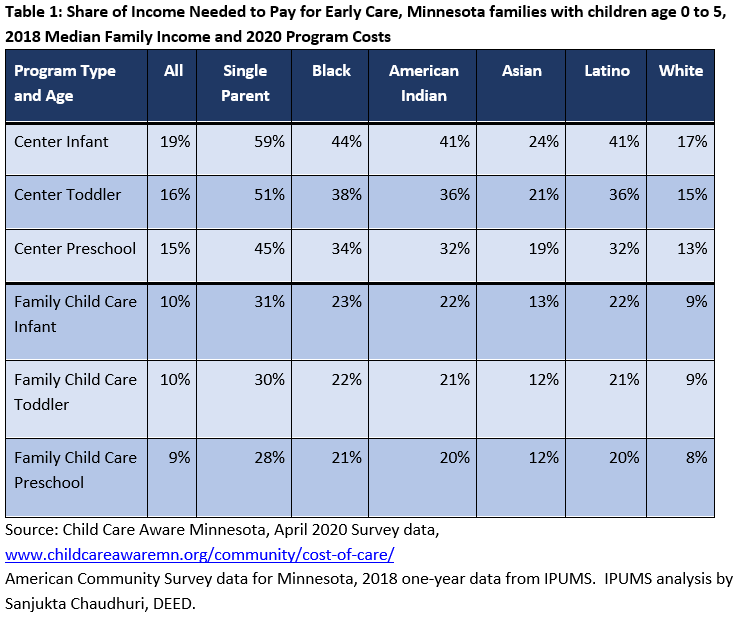

For families with children under six years old, median incomes ranged from $26,463 in single-parent households to $89,483 in two-earner households in Minnesota according to 2018 American Community Survey data. Median income also varies significantly by race/ethnicity, with non-Hispanic white families with children under six earning a median of $89,973 and Black families with children under six earning a median income of $35,231.

Meanwhile, the average cost of full-time care ranges from $311 per week or $15,550 annually for center-based infant care to $150 weekly or $12,000 for family child care based preschool care, based on Child Care Aware Minnesota survey data for 2020. Affordability challenges are clear when child care costs are considered as a percentage of median family income.

Table 1 shows that the share of income necessary to pay for full-time infant care for one child ranges from 59% in median single-parent families to 17% in median white, non-Hispanic families. Many families have more than one child in care at a time. Costs decrease as children move into older classrooms with a higher staff to child ratio which are less expensive to run, but even the cost of a preschooler in family child care requires 21% of median family income in Black families in Minnesota.

While lower-income families (generally those with incomes below 47% to 67% of the State Median Income, depending upon the number and age of children in the family) qualify for subsidies through the Minnesota Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP), the program lacks sufficient funding, and there are waitlists in many counties. As of July 2020, 1,473 families were waiting to get funding. Moreover, despite an increase prioritized by the Governor’s office and passed in the last state legislative session, in most instances subsidies still pay below the average center and family child care costs. This means that not all providers accept these subsidies although the situation has improved due to the recent legislation. These gaps in accessible funding limit families’ choice of providers and ability to find care where and when they need it.

The child care business has historically operated with razor-thin profit margins and very little room to maneuver, as so many of their expenses are fixed costs. Staffing costs are typically 70% of child care centers’ expenses, with 20% going to facilities, leaving only 10% for program expenses, curriculum and administrative costs. As a business concerned with young children’s care and development, child care centers must comply with detailed regulations, including staffing ratios and space requirements. A typical 57-seat child care center in Greater Minnesota operates at a loss even at 85% capacity. It is important to note that 100% capacity is nearly impossible to reach, as children move in and out of different age groups, each with different compliance markers for staffing and space.

Most of the cost of running early care and education programs is in staffing. But because programs rely on parents to pay, they can’t raise prices above what their parents can afford, which means that they often cannot charge enough to compensate staff at a level that meets basic cost of living. Public school based programs also face budget constraints but are generally able to compensate early care and education professionals at a higher level. Meanwhile, after paying the bills so providers can pay themselves, the average hourly wage for family child care providers is $8 an hour, often with 12-13 hour work days (First Children’s Finance, Business Practices of Family Child Care: Expanding What We Know brief, 2016).

As a result, capacity in licensed early care and education has been decreasing around the state. This is particularly true for family child care providers, which are often the most affordable option and the most available option in Greater Minnesota. As capacity has declined as child care providers leave the business, the result has been a documented child care shortage in many areas of the state (Center for Rural Policy and Development, A quiet crisis: Minnesota’s child care shortage, September 2016).

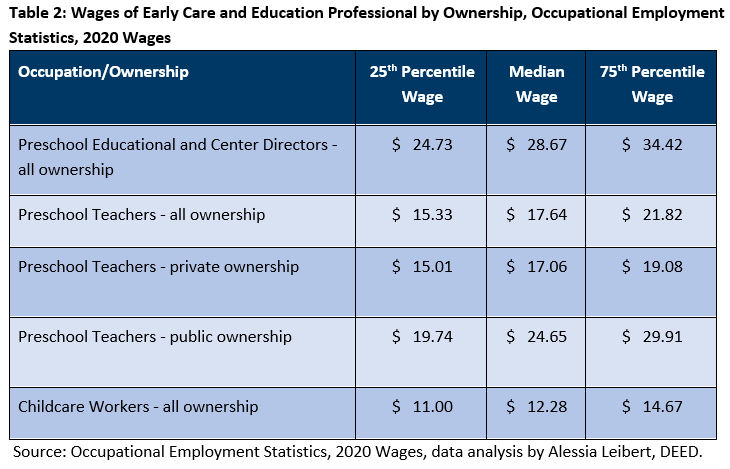

Table 2 shows 2020 wages in Minnesota’s early care and education programs. Wages for preschool teachers, who are required to have a related associate degree in most private centers and a bachelor’s degree in public school settings, are broken out in this table into private and public ownership settings. Private ownership settings are primarily child care centers (rather than family child care, which is absent from this survey). Public settings are primarily public school settings.

Wages for early care and education occupations are critically low compared to other occupations. For Childcare Workers, who, in general, require a high school diploma to enter the field, the median hourly wage in Minnesota, at $12.28 per hour, is one of the lowest among occupations after Gaming Writers and Runners, Gaming Dealers, Locker and Coatroom Attendants, Radio Announcers and Sales Drivers. Occupations such as Security Guards ($16.81), Helpers-Production Workers ($14.62), and Helpers-Carpenters ($17.34), which have similar or lower education and on-the-job learning requirements, earn higher median hourly wages in Minnesota.

The incongruity between wages and education and training requirements is even more pronounced for Preschool Teachers, who must have a related associate degree in most private settings and a bachelor’s degree and teaching license in most public settings. At $17.64 per hour overall, Preschool Teachers earn a lower median wage than any other occupation requiring an associate degree in Minnesota, including Veterinary Techs who earn a median wage of $18.22 per hour in Minnesota and environmental engineering technicians who earn $49,518. Preschool Teacher wages are slightly lower in private settings, at $17.06 per hour in Minnesota, and higher in public settings at $24.65 per hour.

Wages for Preschool Directors and Administrators, at $28.67 per hour, are somewhat more in line with, although still at the low end of, other occupations that require a bachelor’s degree. While a bachelor’s degree is the most typical educational requirement, over 40% of Preschool Directors and Administrators have a master’s degree or higher in Minnesota.

Wages also vary across the state. In general, wages are lower in rural areas, but the share of public programs versus private or non-profit programs greatly impacts median wages. Looking only at wages in private settings across the six Planning Regions, while still very low, the Twin Cities Metro has higher median hourly wages for Preschool Teachers and Child Care Workers than other regions of the state.

Wages in most early care and education occupations are lower than the cost of living for a single person in Minnesota and certainly lower than the cost of raising a family. Based on DEED’s Cost of Living Calculator, the basic cost of living for a single person is $15.09 an hour statewide and $18.20 an hour or $56,772 annually (combined earnings of both wage earners) for a family of three with one full-time worker, one part-time worker and one child (the most typical family structure in Minnesota). Since wages for many people working in early care and education do not sustain a basic cost of living, even in occupations that require a college degree for entry, it is difficult to recruit and retain qualified workers.

One result is high turnover in the industry. The early care and education industry has a higher turnover rate than most other industries in Minnesota. In 2018, the annual turnover rate was 14.4% for the Child Day Care Services industry, while it was 5.9% in Manufacturing, 8.1% in Educational Services, and 8.3% in Healthcare & Social Assistance. Economy-wide in Minnesota, turnover was 9.1%. Turnover increases costs and decreases quality in early care and education programs.

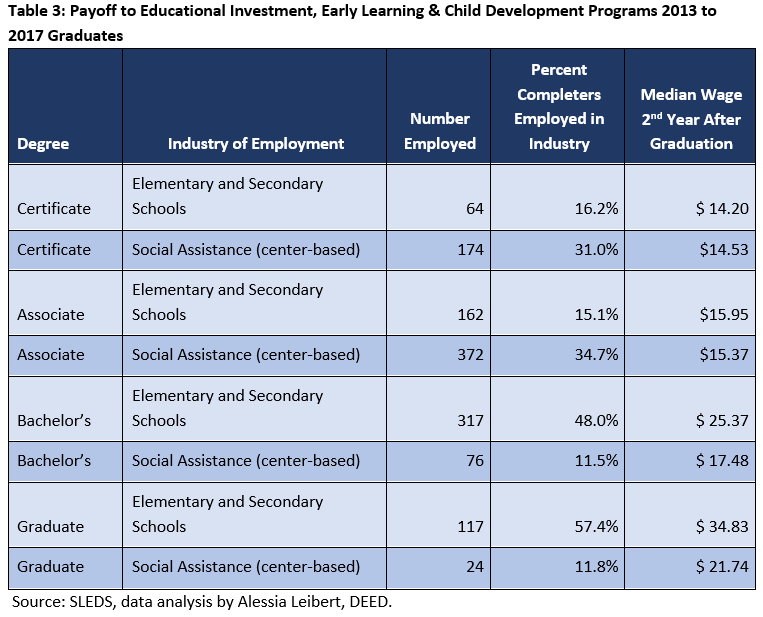

These low wages negatively impact the pipeline of workers entering this industry, creating a critical talent gap. Based on Statewide Longitudinal Education Data System (SLEDS) data, private and non-profit sector wages do not justify the financial burden of obtaining a degree in the field and do not support the cost of repaying student loans.

In Minnesota, graduates with an associate degree in early learning or child development earned a median wage of only $15.37 in center-based child care programs two years after graduation. Those with a bachelor’s degree in early learning or child development who worked in center-based programs earned a median wage of only $17.48 while those who worked in elementary or secondary schools earned $25.37 two years after graduation. Because of the large earnings gap, many graduates with bachelor’s degree or other advanced credentials pursue jobs in public schools, leaving private and non-profit child care programs bereft of highly trained staff (see Table 3).

The early care and education workforce is more diverse in its racial and ethnic composition than many other Minnesota industries. Overall, Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) workers comprise 23% of the workforce compared to only 15% across all Minnesota industries. As a result, BIPOC workers are more likely to absorb the impact of these low wages, resulting in less economic stability and fewer resources for their families and children as well as for their professional development.

The main result of the broken workforce pipeline in the industry in Minnesota is that centers are not always able to hire employees who meet basic staff qualifications. In 2018, the DHS commissioner was given authority to approve additional variances in staff qualifications to address the shortages. While these variances have helped to maintain capacity in the industry, they do not address the need for a more robust pipeline of highly qualified workers to care for young children.

Where there has been a decline in capacity, it has been driven mostly by family child care providers leaving the profession. A recent survey of family child care providers that closed between 2017-19 by the Results Management Team at Minnesota Management and Budget on behalf of the Family Child Care Task Force found that the three business factors respondents listed most often as having a high impact on their closing were: lack of benefits, such as health insurance (40%); long hours (34%); and difficulty finding substitute providers (30%). Low earnings ranked lower as a reason for leaving the profession.

The early care and education workforce is as critical to Minnesota’s economy and business community as it is to parents and young children. Most parents rely on care as they start careers or work to move up in their career. These are precisely the workers that businesses most want to attract, train, and, importantly, retain. They are at the stage of their careers in which businesses are most likely to be investing in them with on-the-job training and education. Especially for women, but increasingly for men, businesses risk losing critical workers if families can’t find high-quality, affordable care that meets their cultural, linguistic and scheduling needs near where they live or work.

More than 311,000 workers, just over 10% of Minnesota’s labor force are parents of children under six years old. In fact, with Minnesota’s high labor force participation rate, we have the highest rate (tied with a few states) of children under age 6 with all available parents in the workforce (Annie E. Casey Foundation KIDS COUNT Data analysis of ACS data). While some of these families manage to juggle work schedules or rely on family, friends or neighbors to care for their young children, most at some point need to turn to formal care arrangements, and all should have access to affordable quality child care when and if they need it.

Before the pandemic took hold, child care was in the top three issues that businesses raised with DEED and state legislators. We know that businesses and groups across Minnesota are actively attempting to tackle the lack of child care availability. Legislative hearings addressing issues in this industry have featured testimony from businesses in Central and Southeast Minnesota, including Hormel and the Minnesota Farm Bureau Federation, about what they are doing to address this issue. Hormel representatives shared their struggles with attracting top talent to their Fortune 300 Company because of the lack of quality child care in their community. They also experience difficulty with employee retention due to the shortages of early care and education. They reported that some parents are using unlicensed care because they are desperate. The Hormel Foundation has gone so far as to work on creating new child care slots and testified that it took two years of hard work to create just 12 new slots.

The early care and education industry also shapes Minnesota’s future workforce. Research in neuroscience and developmental psychology has established early childhood as a critical juncture for the physical, cognitive-linguistic, and socio-emotional development that undergirds every individual’s lifelong well-being. During the first five years of life, a child’s brain develops more than during any other period, and, by age five, a child’s brain has grown to about 90 percent of its adult size (Brown & Jernigan, 2012). The neural connections and skills that emerge in early childhood impact future success in school, employment, and society (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2007).

The promising results of the “Big Three” longitudinal studies of early childhood education: the Perry Preschool Study; the Carolina Abecedarian Project; and the study of the Chicago Child-Parent Center Program provided substantial evidence that government investment in early childhood development could produce significant returns for society (Reynolds et al., 2010). Longitudinal studies of those who participated in high-quality early care and education programming, show reductions in toxic levels of stress, criminal justice system involvement, and reliance on social insurance programs, as well as increases in educational attainment, employability, lifetime earnings, and even intergenerational health and education.

These individual improvements translate to significant savings in health, legal and social insurance costs, as well as improved economic output and opportunity (Campbell et al., 2002; Nores et al., 2005; Camili et al., 2010; Englund et al., 2014; Reynolds et al., 2014; Reynolds 2018). Most famously, James Heckman, a Nobel-prize winning professor of economics from the University of Chicago, developed the “Heckman Equation” from his study of the Perry Preschool Project, which shows a 13% return on investment for education for children aged zero to five (Heckman et al., 2010). This evidence has served as the underlying justification of the Human Capital Model, as well as a significant incentive for local, state, and federal governments to increase financial and technical support for increasing access to the high-quality early care associated with these high social and economic returns and supporting sustainable wages for the educators and administrators who staff them.

What Minnesota was doing prior to the pandemic to address the crisisMinnesota's Children's Cabinet is an interagency partnership charged by Governor Tim Walz with taking a data-driven and results-oriented approach to create a state government centered on improving outcomes and aligning resources for all children, youth and families. The cross-agency network of the Children's Cabinet works to build collaborative relationships with the community including those administering services to children. The Children's Cabinet is convening cross-agency leaders to address five priority areas including early care and education. These leaders are identifying strategies and actions so that all families have access to child care so business and community can thrive. DEED's Child Care Economic Development Grants are part of these broader multi-agency efforts to ensure Minnesota families have access to quality child care. In October 2019, DEED awarded a total of $727,500 in Child Care Economic Development Grants to 11 organizations throughout Minnesota to increase families' access to quality child care. Last October's grants were the third round, which in total have awarded $1.7 million to organizations throughout Minnesota to increase access to quality child care. Altogether, these grants are projected to leverage more than $11 million in local investment and open up an additional 4,354 child care slots throughout the state. Although funding has expired at this point, the state legislature will likely take up consideration of additional grants in the next legislative session. Child Care Economic Development Grants are made to help fund child care business startup or expansion, training, facility modifications or improvements required for licensing, and assistance with licensing and other regulatory requirements. |

The State of Minnesota acted quickly when the pandemic forced business shutdowns, work from home and other disruptions during spring 2020. The market for child care contracted dramatically. Child care businesses experienced severe reductions in enrollment as parents took their children out of care, either out of concern about exposure to the virus or because they had lost their job or were working from home. Some child care centers and providers have reported that the numbers of children they were caring for plummet by as much as 75% over the course of just a few weeks. These severe reductions in enrollment, along with mandatory closures where COVID-19 exposure is documented, have resulted in drastic revenue loss for child care businesses.

This forced providers to furlough staff, delay rent payments and take other necessary steps to stay afloat for families still depending on them. Additionally, they needed to implement health and safety measures to slow the spread of the coronavirus, incurring new costs for personal protective gear like face masks, additional gloves and hand sanitizer and changes to staff processes to ensure social distancing. The Education and Child Care Workgroup, a cross-agency team formed by the Governor's Office to respond to education and child care needs during the peacetime emergency worked with the Department of Human Services and their grantee, Child Care Aware of Minnesota to procure critical supplies worth over $300,000, receive donations of hand sanitizer and bleach and distribute them to child care providers across the state as the end of August.

The state of Minnesota distributed three rounds of Peacetime Emergency Child Care Grants from April through June, 2020. As part of their COVID-19 Response Supplemental Budget, Gov. Tim Walz and Lt. Gov. Peggy Flanagan proposed an initial $30 million in funding for emergency grants for licensed child care providers serving essential workers during the COVID-19 public health emergency. In June, an additional $10 million was added to the program from federal child care funds authorized in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which has been dispersed in 5,400 awards to providers.

The Minnesota Department of Human Services, Governor's Children's Cabinet, and Child Care Aware of Minnesota worked together to distribute these funds. The grants helped child care businesses remain open to care for the children of essential workers. These grants may have helped to avoid further disruptions to the early care and education industry that could worsen the existing child care shortage in the state.

Emergency funding from the state complemented federal assistance available through the Small Business Administration's Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans and Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL), and other emergency federal funding. This emergency funding from the state has helped preserve the essential early care and education infrastructure in Minnesota better than most other states, and as of July 2020, licensed child care capacity in Minnesota remains stable. Emergency funding was able to keep 89% of licensed family child care providers and 67% of child care centers in Minnesota operating based on the most recent data available which is from April to May. In Iowa, only 50% of child care providers that were operating at the beginning of 2020 remained in business after mid-March. This is the case in many other states as well; and this could prove a barrier to economic recovery as some parents will not be able to return to work because they don't have access to child care.

However necessary and helpful additional emergency assistance is now, it doesn't address the underlying and long-standing challenges to industry stability. Nor does it entirely make whole the already underpaid workforce. For example, while staff may be covered under FFCRA or can access Unemployment Insurance (UI), these measures have not been sufficient to cover full wages during closures for many staff. Through September, 6,800 Childcare Workers and 3,570 Preschool Teachers have applied for UI. This has resulted in a crunch between health and safety and the economic stability of workers. The fear is that, out of necessity, many will leaved the early learning and education workforce all together to pursue more stable and well paid employment.

At the direction of the Administration, the Education and Child Care workgroup brought forward a proposal for use of Coronavirus Relief Funds to provide COVID-19 Public Health Support Funds to operating licensed family child care programs, licensed child care centers and non-profit certified centers. This funding supported the increased costs to implement the public health guidance including additional costs for cleaning and staffing to implement cohorts of children to slow the spread of COVID-19. During the funding period of July, August and September, just more than $51 million were dispersed. A proposal to extend this funding to include payments in October, November and December was approved for $53.3 and expanded availability to all certified centers in addition to those eligible previously.

This article lays out the case that the early care and education industry was in crisis in Minnesota prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has exacerbated the challenges it faces. A workforce pipeline that does not produce enough candidates for programs to meet basic health and safety needs in Minnesota and the resulting compromised quality of, and access to, care all point to a need for fundamental changes in the industry and its funding mechanisms. Rob Grunewald of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve points out that well-designed public funding and policies can bridge the gap between what it costs to provide high-quality care and what parents can afford to pay. Public support for the industry during the COVID-19 pandemic has helped prevent the industry from further losing capacity, but as those supports disappear, programs may be in worse financial shape than before March 2020.

If this is the case, it could limit the ability of parents with young children to fully participate in Minnesota's labor market and businesses to find the qualified workforce they need. This constraint would compromise Minnesota's efforts to recover from the COVID-19 recession and toward a labor market that works for all families, children and businesses in Minnesota.

The next article in this series will focus on what it would take to reestablish a workforce pipeline and eliminate the talent gap in the early care and education industry. We will examine what a viable career ladder would look like and how could it be established. Stay tuned for this next article, due out in December 2020.

Zina Noel is a doctoral student in Human Development and Social Policy at Northwestern University. She studies comparative domestic and international policy around the first five years of life, focusing on workforce development and culturally responsive and community-based practices. Previously, Zina has worked as an early childhood educator and in research, policy, and strategy development for education and early childhood initiatives in the U.S. and abroad. Zina has a Master's in Education from Harvard Graduate School of Education in International Education Policy and a post- baccalaureate certificate from the University of Minnesota's Humphrey School of Public Affairs in Early Childhood Policy.

Suzanne Pearl joined First Children's Finance as Minnesota Director in 2019. She has 20 years of experience in nonprofit management, mainly in the areas of international community development and humanitarian relief. A lawyer by training, Suzanne also has experience in public policy and nonprofit management consulting. She holds a Juris Doctor from Hamline University School of Law and a Bachelor of Arts in History from the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities.

We'd like to thank Jenny Moses and Stephanie Hogenson at the Minnesota Children's Cabinet for fact checking and adding important information, particularly on the current COVID-19 crisis, to this article.