by Alessia Leibert

June 2021

This study presents early findings about Minnesota workers who were laid off during the first months of the pandemic (March through June of 2020) and the most up-to-date information we have about their employment status.

Specifically, the study considers:

The information about how different groups of workers fared is analyzed by part-time/full-time and regular/seasonal status, wage level, racial and ethnic background, industry and occupation.

This analysis highlights the need to help workers laid off from industries where employment may recover more slowly move to higher demand industries that have a better chance of providing stable employment. It finds that the same challenges that hindered hiring pre-pandemic, including racial disparities and biases, skills gaps, location mismatch, less desirable work conditions and low-paying jobs continue and are in some cases exacerbated by conditions caused by the pandemic.

This article points to some steps that could be taken to help address these challenges and connect Minnesotans who need work with the employers who need them.

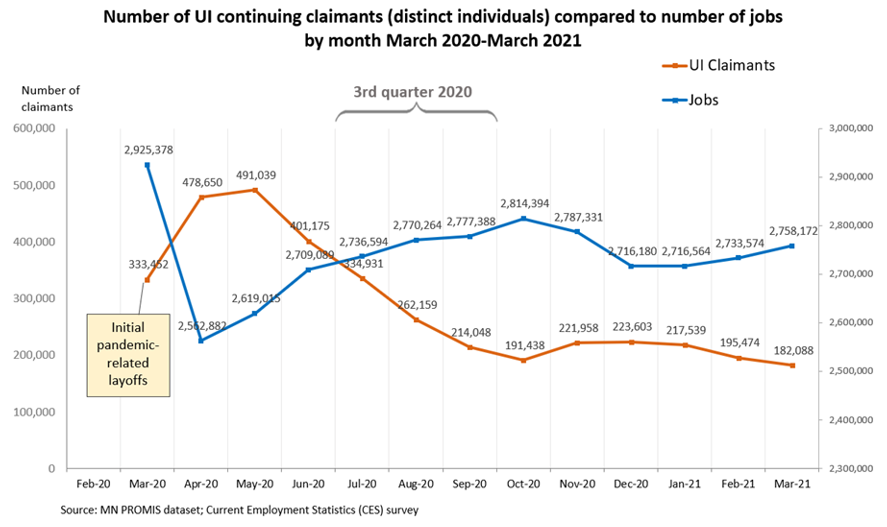

From March 2020 to March 2021, 786,617 Minnesotans eligible for UI filed for benefits. This represents 26% of Minnesota's workforce. Figure 1 tracks claimants by month from the start of the pandemic and compares them to the number of jobs. It shows that the two measures move opposite one another. When the number of jobs peaked in October 2020 the number of claimants fell to one of its lowest points (191,427). Job numbers fell again in November reflecting the high rate of COVID-19 infections at that time and a second round of measures to slow its spread, and gradually rebounded in February 2021.

Figure 1. Number of UI Continuing Claims (distinct individuals) compared to number of jobs by month March 2020-March 2021

Third quarter 2020 represents the first phase of job rebound in Minnesota since the start of the pandemic. During this period, the number of jobs once again surpassed the number of UI claimants as shown by the point at which the blue and orange lines cross for the second time. Third quarter 2020 is also the latest available quarter of UI wage records, which allow tracking of individual workers from unemployment to re-employment.

This article will examine how many Minnesotans who filed a UI claim in the early months of the pandemic returned to work in third quarter 2020, and with what outcomes.

Table 1 summarizes the net results of movements in and out of employment from the base period to 3rd quarter 2020 for 631,040 claimants1 to identify how many returned to work and how many did not.

| - | Workers who filed a UI claim from March to June 2020 by employment status in Summer 2020 | % of total UI claimants | % requested UI benefits again in Oct-Dec 2020 | Median weeks of UI claimed before July 2020 | Median difference in quarterly wages pre-post layoff* | % workers whose hourly wages** fell by >=10% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMPLOYED | Recalled by same employer that laid them off

N=374,986 |

59% | 33% | 7 | +$132 | 16% |

| Continued working second jobs***

N=46,935 |

7% | 46% | 9 | -$2,778 | 21% | |

| Changed employer

N= 56,800 |

9% | 35% | 9 | -$130 | 32% | |

| NOT EMPLOYED | Did not return to work and continued to request UI benefits

N=133,115 |

21% | 80% | 14 | NA | NA |

| Did not return to work and did not file a UI claim after June 2020

N=19,204 |

3% | 0% | 6 | NA | NA | |

| - | Total N=631,040**** | 100% | 43% | 9 | -$15 | 19% |

| *The pre-layoff period is defined as the period from Summer (q3) 2019 to Winter (q1) 2020. The post-layoff period corresponds to q3 2020.

**Hourly wages represent jobs with valid reported hours and were calculated across all jobs held, not only in the jobs that were lost. ***This group represents claimants who were working multiple jobs before the pandemic and returned to one of these jobs in q3 2020. Furthermore, this group includes 6,000 claimants with missing employer information and who, therefore, could not be included in Group 1. ****Representing distinct (unduplicated) claimants who were monetarily eligible for UI benefits and were employed in the period q3 2019-q1 2020. |

||||||

The first key take-away from this analysis is the very large share of claimants, 59%, who were recalled by the same employer during summer 2020 (the first group in Table 1). Fewer broken bonds between employee and employer is good news for the recovery. During the first half of the year these workers had the shortest spells of unemployment compared to any other group other than group 5, a median of 7 weeks. However, not everyone in this group was able to return to stable employment. Thirty-three percent were laid off or furloughed again after September 2020 and it is still unclear whether they have been recalled or not.

The good news is that hours and earnings losses for Minnesotans recalled by the same employer during the summer of 2020 were very mild. Quarterly wages actually increased for at least half of individuals in this group, with a median increase of $132 during third quarter 2020. Another indicator of the mild impact of the COVID-19 recession on this group of claimants is the very small share, 16%, who suffered a pay cut greater than 10% of their pre-pandemic wage. This suggests that the overwhelming majority of claimants were called back at the same wage and kept the same job role.

Workers in Group 2 of Table 1 were not called back by the employer that laid them off but were able to continue working a second job they had pre-pandemic. The median duration of unemployment, 9 weeks, was a bit higher in this group compared to the first, and not surprisingly the wage penalty was also higher because of foregone hours (a median loss of $2,778 in quarterly earnings). Furthermore, 21% of workers in Group 2 experienced a wage loss greater than 10% of their pre-pandemic wage, suggesting that one out of five may not have returned to their same job role or occupation.

Workers in Group 3, representing only 9% of the total, found a new employer. Since workers in this group started from a lower earnings level than workers in Group 2, as a group they had a smaller loss in wages in absolute terms (a median of -$130 compared to -$2,778) but in relative terms they fared much worse. In fact, 32% of workers in this group suffered a wage loss greater than 10% of their pre-pandemic wage. This is not surprising given the fact that breaks in employee-employer bonds often push workers to accept job offers at a lower salary than pre-layoff.

Workers in Group 4, representing 21% of the total, bore the brunt of the pandemic recession. Four out of five (80%) continued to request benefits in 4th quarter 2020. Their claims history shows a gap in filing in October and early November, suggesting that some came back to work and were laid off again in late November when new virus containment measures were enacted. Fluctuations in infection rates, and corresponding changes in government-mandated business restrictions, are key to understanding individuals' decision-making regarding when to return to work in this recession2. Since this group spent more time out of work than other groups, a median of 14 weeks by July 2020, we can assume that they would have suffered the largest relative employment earnings losses if it had not been for the temporary supplemental UI benefits which in this period went from $600 a week through the end of July to $300 in the remainder of the quarter.

The last group, Group 5, is extremely small (3%) and hard to interpret because their motivation not to request UI benefits despite being out of work cannot be evinced from the data. Some of these individuals could have dropped out of the labor market in fear of contracting the virus, waiting until later in the year to return to work3. Some may have chosen to retire. However, we cannot confirm if they in fact did return to work until the release of employment records for Fall 2020 and Winter 2021.

Of the five groups, Group 4 is the most at risk of prolonged unemployment. One out of five (20%, a slightly higher rate than other groups) were laid off from the Leisure & Hospitality sector. Therefore, the prospects of returning to work depend on how quickly the Leisure & Hospitality sector recovers and/or on these workers' ability to transfer to other industries, as will be discussed later in the article. One important characteristic of this group is that is has the highest concentration of Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) at 33%. The group with the lowest concentration of BIPOC Minnesotans, Group 1, fared relatively better than others.

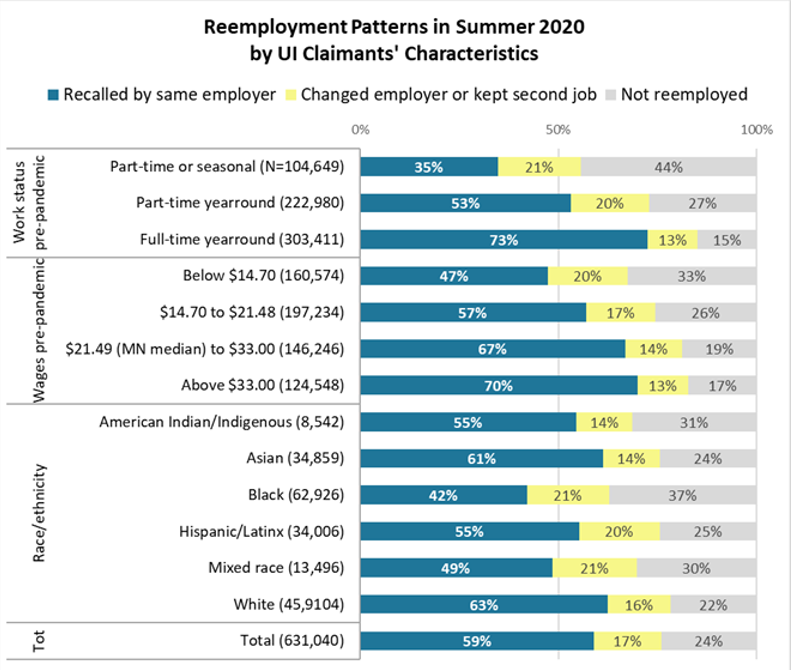

Figure 2 aggregates the groups in Table 1 into three categories instead of five for the sake of simplicity. These three groups are: workers who were recalled by their employer, workers who switched employer or continued working in a second job, and workers who did not return to work (not reemployed). Figure 2 shows clearly that workers of color had the most difficulty returning to work during this time period. Work status and hourly wages before the pandemic are also included in Figure 2. Workers with lower wages and those who worked seasonal or part-time prior to the pandemic were less likely to return to work during third quarter 2020.

Figure 2. Reemployment Patterns in Summer 2020 by UI Claimants' Characteristics

UI claimants who were employed part-time and/or earning below $14.70 per hour were more likely to not return to work and remain on UI. This implies that the highest earning workers were able to weather the crisis without widespread displacement while the working poor were more likely to have suffered permanent job and income losses.

Figure 2 also reveals stark differences by race. Black workers were the least likely to be recalled by their employer, only 42%. They were also the most likely to be out of work (37%), followed by American Indians/Indigenous (31%) and claimants of mixed race (30%). These racial disparities are independent of workers' region of residence4.

Overall, claimants who continued to receive UI in Summer 2020 without returning to work - Group 4 in Table 1 – were the lowest wage workers and therefore least likely to have savings or investment income to tide them over. The Federal weekly addition of $600 ended on July 25 and the temporary federal Lost Wages Assistance (LWA) addition of $300 did not start making payments until the week ending September 5. LWA only ended up providing the $300 supplement for six weeks with payments retroactive to July 26. The lack of clarity about the short LWA program makes it unlikely that UI supplements acted as a disincentive to return to work between July and September 2020.

The fact that 47% of workers earning below $14.70 per hour and 57% of those earning from $14.70 to $21.48 returned to their employer during the summer of 2020 suggests that, when given the chance, Minnesotans overwhelmingly chose to go back to work rather than remain on UI. Furthermore, about 20% of the lowest wage earners changed employers, indicating successful job search activities and a desire to return to work. Finally, even among workers whose pre-pandemic earnings were $21.49 an hour and higher, the not reemployed were still in the double-digits (between 17% and 19%). This suggests that there is a natural floor, ranging from 17% to 19%, of workers who did not return to work for reasons that have little to do with wages5. Fear of the pandemic, childcare challenges, inability to take other jobs, and/or the expectation to return to their jobs soon might have induced these workers to sacrifice some of their potential earnings.

This evidence shows that the pandemic took a greater toll on workers who were already struggling with a wide range of barriers to maintaining stable employment. Examples of barriers associated with a higher risk of prolonged unemployment are racial disparities, disability, older age and low educational attainment6.

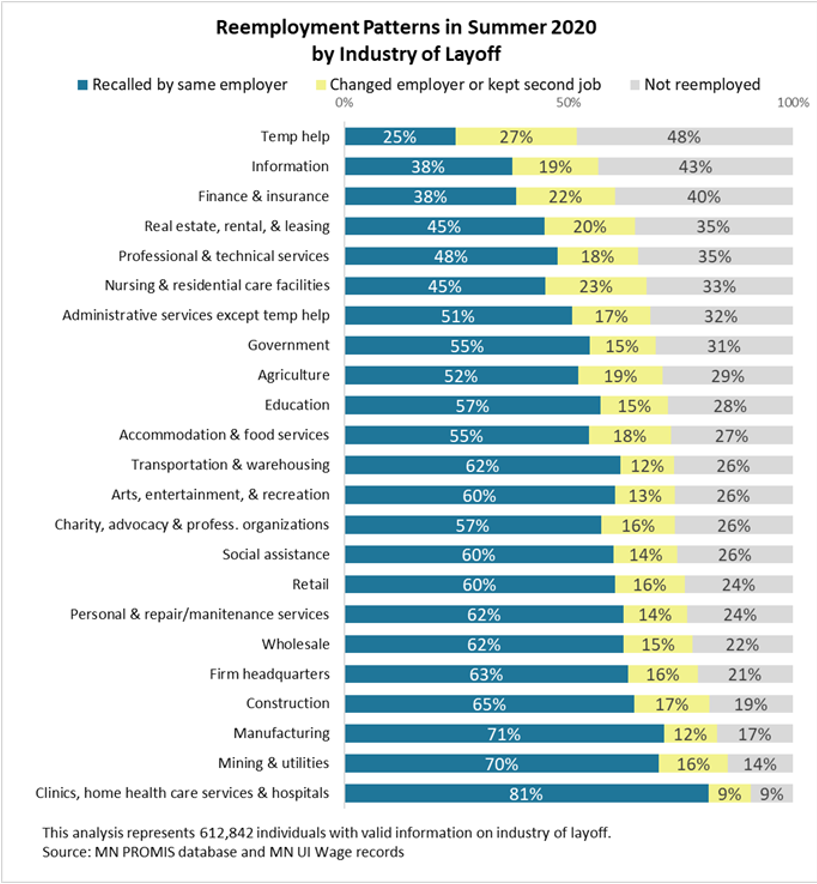

Which industries experienced the largest long-term loss of workers? Figure 3 presents the same data as Figure 2 broken down by industry of layoff.

Temp Help had by far the lowest share of recalled workers (25%) and the highest share of claimants who did not return to work (48%). Given the short-term nature of employment in this sector, the industry is rebounding from these losses as the economy picks up steam, but workers in this industry are more vulnerable than others to permanent layoffs. Moreover, Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) are over-represented in this sector. Therefore, workers laid off from this sector ought to be targeted with interventions aimed at alleviating barriers to finding stable employment.

At the other end of the spectrum, the industries with the highest shares of recalled workers are Clinics, Home Health Care Services & Hospitals (81%), followed by Manufacturing (71%), Mining & Utilities (70%), Construction (65%), Firm Headquarters (63%), and Wholesale (62%). These industries also had the lowest shares of not reemployed claimants. This is not surprising considering that these workers are predominantly on permanent or union-backed work contracts and/or they perform essential activities that were largely exempt from the temporary shutdowns or other restrictions during the pandemic.

Figure 3. Reemployment Patterns in Summer 2020 by Industry of Layoff

Are claimants from industries at the top of Figure 3 at high risk of prolonged unemployment? According to the Profile of Risk for Prolonged Unemployment analysis the answer could be yes for Information, Administrative services, Real Estate/Rental/Leasing, and Nursing & Residential Care Facilities. For example, job cuts in Information, especially news media and cable services, are likely to continue because of automation. Real Estate/Rental/Leasing might suffer permanent losses if the growing use of remote work technologies curtail the need for business travel and, thus, car rental services. Likewise, Administrative services might continue to experience layoffs in the future because, as employers take advantage of remote work to reduce their footprint, some building maintenance, security, and front-desk jobs may not come back.

Finally, layoffs in Nursing & Residential Care facilities and Government are related to each other and driven not only by reductions in face-to-face services due to COVID-19 but also by budget cuts in government programs that started prior to the pandemic.

What about Accommodation & Food Services? Why is the share of not reemployed in this hard-hit industry not greater than 27%? The answer has to do with seasonality. Part-time work in these sectors always ramps up in the summer, offering laid off workers additional opportunities to return to work for a different employer or continue working in a second job, as we can see from the high share (18%) of claimants who changed employer or returned to an alternative employer. This result is encouraging.

Another important question is what kinds of jobs were lost during the early months of the pandemic and which ones appear more at risk of not coming back.

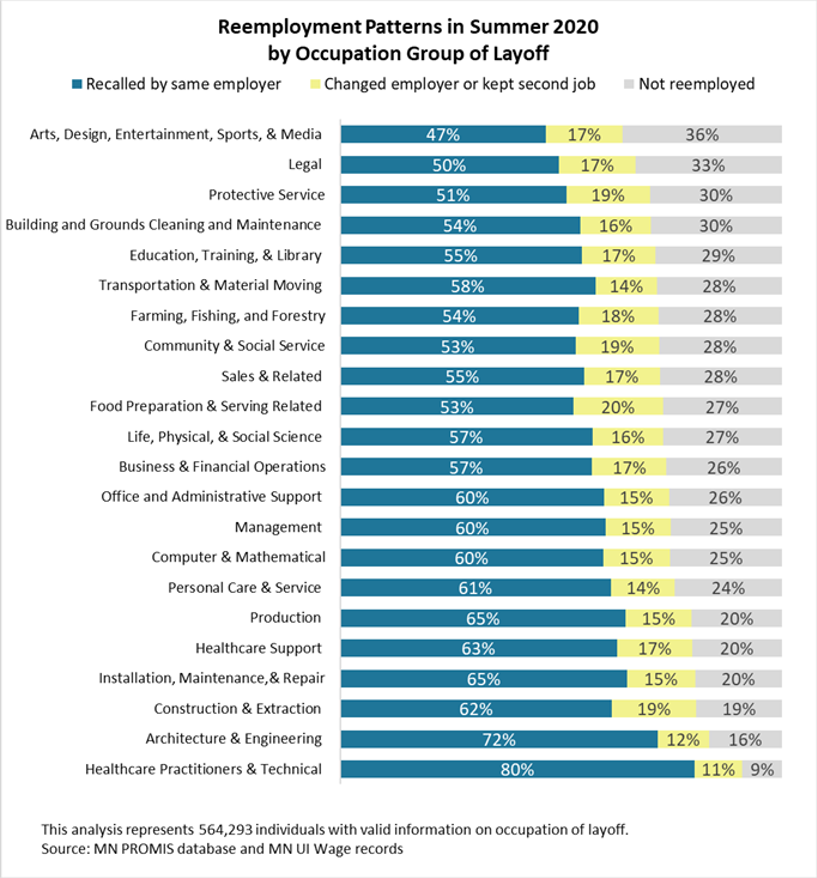

As Figure 4 shows, the types of occupations with the highest shares of workers leaving their employer and not returning to work - and therefore more at risk of long-term unemployment - are Arts, Design, Sports & Media, Legal, Protective Service, and Food Preparation & Serving occupations7.

Higher recall rates were found among Healthcare Practitioners (80%), Architecture & Engineering (72%), Installation/maintenance & Repair (65%), and Production (65%). These occupations are predominantly employed in the industry sectors shown in Figure 3 as the quickest to recall workers: Clinics & Hospitals, Manufacturing, Mining & Utilities, and Construction.

Figure 4. Reemployment Patterns in Summer 2020 by Occupation Group of Layoff

Claimants from Food Preparation & Serving had almost identical outcomes as the industry most of them originated from, Accommodation & Food Services (see Figure 3) with a 53% recall rate. The relatively high rates of claimants who changed employer or kept a second job (20%) helped keep the rate of not reemployed lower than many other occupational groups. This is good news because Food Preparation & Serving represents by far the biggest group of claimants, at 89,042 and is therefore a driver of overall ability to get back to work.

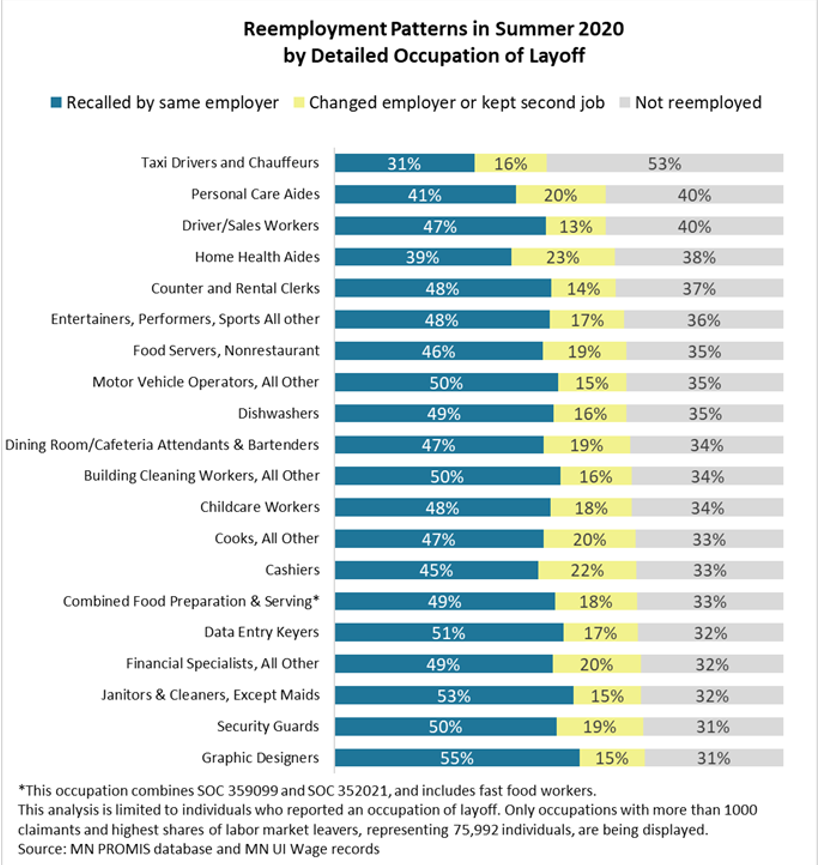

Which occupations are more at risk of long-term job losses? Figure 5 presents the top 20 occupations that had more than 1,000 claimants and higher percentages of not reemployed in 3rd quarter 2020.

Figure 5. Reemployment Patterns in Summer 2020 by Detailed Occupation of Layoff

Occupations requiring moderate skills, or skills beyond entry-level, such as Supervisors of Food Preparation and Serving workers, do not make the list in Figure 5 because they had recall rates of 57% and only 25% of not reemployed claimants. This evidence suggests that claimants with higher skills, even in hard-hit industries, were more likely to be recalled or to find a new position quickly.

Once again, we find that hardest-hit occupations are predominantly low-skilled, low wage (except for Graphic Designers), and part-time. They are also exposed to three major vulnerabilities: first, they tend to rely heavily on face-to-face contact with customers; second, they are subject to the risk of automation, especially Counter & Rental Clerks, Data Entry Keyers, Graphic Designers and Financial Specialists due to the growth of online banking and ecommerce in general; and third, most of these job functions cannot be performed remotely. The first vulnerability can be overcome as more individuals get vaccinated. We are already seeing a hiring rebound in occupations such as PCAs, Home Health Aides and Childcare Workers, which are all in extremely high demand and more workers will be able to return to work safely in these occupations as vaccination rates increase. The second and third, however, may not be overcome if employers change their staffing patterns permanently in favor of remote work and labor-saving technologies, a process that began before the pandemic. It is important to continue to monitor these trends and start boosting digital literacy in the workplace, especially among workers with no formal education beyond high school who are more at risk of being left behind by these global transformations.

The information presented in Table 1 suggests that the need for reallocating unemployed workers to different industry sectors in Minnesota has been, at least so far, very low. Two out of three (66% of claimants) were recalled or kept working for previous employers. Only 6% of claimants (35,673 individuals, a subset of Group 3) transitioned to a different industry in 3rd quarter 2020.

Table 2 examines industry transitions8 for these workers with the goal of identifying sectors that offered them the most realistic paths toward reemployment. For reasons of space, we present a detailed industry breakdown only for the three super-sectors with the highest number of claimants engaged in industry transitions: Leisure & Hospitality (which includes Accommodation & Food Services and Arts, Entertainment & Recreation); Retail; and Manufacturing.

Table 2. Transitions from unemployment to employment in a different industry sector in 3rd quarter 2020, by sector of layoff

| Industry sectors of layoff | Industry sectors of reemployment July-Sept 2020 | Shares within initial industry | Detailed industries that hired most industry switchers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leisure & Hospitality (N=6,810) | Retail trade | 23% | Gas stations; Grocery Stores; General Merchandise Stores; Building Material and Supplies Dealers |

| Temp help | 9% | Temporary Help Services | |

| Nursing & residential care facilities | 7% | Continuing Care Retirement Communities; Skilled Nursing Facilities | |

| Administrative services except temp help | 7% | Services to Buildings and Dwellings | |

| Manufacturing | 6% | Beverage manufacturing; Bakeries/tortilla manufacturing | |

| Transportation & warehousing | 6% | Express Delivery Services | |

| Other | 40% | - | |

| Retail (N=4,430) | Accommodation and food services | 15% | Restaurants and Other Eating Places |

| Temp help | 10% | Temporary Help Services | |

| Transportation and warehousing | 8% | Warehousing and Storage hubs for products to be home-delivered | |

| Manufacturing | 7% | Food manufacturing | |

| Administrative services except temp help | 7% | Services to Buildings and Dwellings | |

| Construction | 6% | Specialty Trade Contractors | |

| Other | 46% | - | |

| Manufacturing (N=3,557) | Temp | 24% | Temporary Help Services |

| Retail trade | 13% | Building Material and Supplies Dealers | |

| Construction | 11% | Building Equipment Contractors; Foundation, Structure, and Building Exterior Contractors | |

| Wholesale | 8% | Machinery, Equipment, and Supplies Merchant Wholesalers | |

| Administrative services except temp help | 7% | Services to Buildings and Dwellings | |

| Transportation & warehousing | 6% | Warehousing and Storage for products to be home-delivered | |

| Other | 31% | - | |

| All other industries (N=20,861) | Retail trade | 13% | - |

| Temp help | 10% | Temporary Help Services | |

| Manufacturing | 8% | - | |

| Accommodation & food services | 7% | Restaurants and Other Eating Places | |

| Construction | 6% | - | |

| Transportation and warehousing | 6% | - | |

| Other | 50% | - | |

| Total (N=35,678) | Retail trade | 13% | Gasoline Stations; General Merchandise Stores; Grocery Stores |

| Temp help | 11% | Temporary Help Services | |

| Accommodation & food services | 7% | Restaurants and Other Eating Places | |

| Manufacturing | 7% | Plastics Product Manufacturing (especially packaging for medical products); Animal Slaughtering and Processing | |

| Construction | 7% | Building Equipment Contractors | |

| Administrative services except temp help | 6% | Services to Buildings and Dwellings | |

| Transportation & warehousing | 6% | Warehousing and Storage for products to be home-delivered; Express Delivery Services | |

| Nursing & residential care facilities | 5% | Residential Mental health facilities | |

| Clinic, home health care services & hospitals | 5% | Hospitals | |

| Professional & technical services | 4% | Computer Systems Design and Related Services (cloud computing, integration of computer hardware, software, and communication technologies) | |

| Social assistance | 4% | Individual and Family Services; Child Day Care Services | |

| Wholesale | 4% | Grocery and Related Product Merchant Wholesalers | |

| Firm headquarters | 3% | Management of Companies and Enterprises | |

| Finance & insurance | 3% | Depository Credit Intermediation (banks) | |

| Education | 3% | Elementary and Secondary Schools | |

| Personal & repair/maintenance services | 3% | Personal care services (hair salons); Automotive Repair and Maintenance | |

| Real estate, rental & leasing services | 2% | Real Estate | |

| Arts, Entertainment & Recreation | 2% | Other Amusement and Recreation Industries (golf courses, country clubs, skying facilities) | |

| Government | 2% | Executive and Legislative Government Support | |

| Information | 2% | Software Publishers | |

| Charity, advocacy, and professional organizations | 1% | Civic and Social Organizations | |

| Agriculture | 1% | Crop Farming |

In general, we expect the industries that accounted for greater numbers of unemployed workers (Accommodation & Food services, Retail, Manufacturing, Construction, Administrative Services, Transportation & Warehousing) to also have a greater share of incomers from other sectors for reasons of sheer size. This is precisely what we see in Table 2. However, the net balance of losses and gains varies by industry. For example, of the 35,673 workers who switched, Retail absorbed 13%, nearly twice as many as either Manufacturing and Construction. Retail posted net gains, losing 4,430 and picking up 4,699 from other sectors. Construction and Temp Help also posted net gains, while Manufacturing suffered a net loss (3,557 lost versus 2,403 gained).

Accommodation & Food Services, despite being hard hit, picked up the same share of workers from other sectors as Manufacturing and Construction (7%).

Retail played a significant role in the reemployment labor market. Not only did it absorb one out of four (23%) workers laid off from Leisure and Hospitality, but also 13% from Manufacturing. The main reason for Retail's power of attraction is skills compatibility with displaced workers and the fact that it offers part-time, flexible work schedules that allow certain categories of individuals typically employed in the food service industry - for example women, college-age, and retirement-age individuals - to balance work, family, and school.

Inconvenient work shifts are a well-documented reason why some job openings in Manufacturing go unfilled9. At a time when telecommuting and flexible work schedules are becoming the norm, employers who cannot offer these perks to jobseekers might find themselves at a disadvantage in the talent race.

Clinics & Hospitals had a net gain of about 800, but the workers that moved into this sector did not originate from the hardest-hit industries. This is due to the specialized training requirements needed to work in Clinics & Hospitals relative to other healthcare employers. Likewise, Construction had a net gain of 600, but its ability to reemploy workers from hard-hit sectors is very limited.

The fourth column in Table 2 shows the types of businesses that picked up the most switchers. These industries were best positioned to offer products and services that replaced those that were unavailable or restricted. For example, when restaurants closed people spent a larger share of their budget in Grocery Stores and General Merchandise Stores. This information also reveals the importance of skills compatibility in making employment reallocations possible. For example, the Manufacturing employers that absorbed most Leisure & Hospitality workers were Beverage Manufacturers and Bakeries/tortilla Manufacturers, while the top retailers were Gas Stations and Grocery Stores and the top healthcare employers were Retirement Communities. These switches were able to happen because food preparation skills are common to all these industries.

Finally, Transportation & Warehousing falls among the top six industries of reemployment for the three highlighted sectors and overall. The lion's share of incoming workers was taken by Express Delivery Services which grew in response to the growing "stay home economy". It's official: the ubiquitous delivery trucks offered reemployment opportunities for laid-off workers. Shifts in consumer habits also benefited Building Contractors and Building Supplies Retailers as people spent more on home improvement projects.

Other industries whose growth is directly linked to the boom in online shopping include Cloud Computing Services, Packaging Manufacturing, and Warehousing Hubs. If shifts in consumer habits become permanent these businesses could define the new economic landscape post-pandemic.

The location of businesses that rebounded more quickly than others also played a role in driving job flows in and out of industries. For example, claimants from Northeast and Northwest Minnesota who switched industry were more than twice as likely (15% versus 7%) to switch to Accommodation & Food Services as claimants in more urban regions which were heavily affected by restaurant and hotel restrictions. The mismatch between the location of types of businesses that were hiring in 2020 and the location of unemployed workers with the needed skills and experience made it more challenging for workers in the Twin Cities Metro to return to work or find new work relative to workers in Greater Minnesota.

Lastly, workers' age played a role in industry transitions, too. Reemployed claimants who were 25 years old or younger were twice as likely as their 25 to 50 year old peers and four times more likely than claimants over 50 to engage in industry transitions. Young workers' higher propensity to switch might be explained by their weaker ties with their pre-pandemic employers (and, therefore, the lower expectation of being recalled) or by employers' bias against hiring older jobseekers. Furthermore, since claimants who changed employer suffered a greater relative wage loss than other reemployed claimants (as shown in Table 1 for Group 3), another reason why younger people are over-represented among industry switchers might be that they were in a better position to take a pay cut than older claimants with families to maintain.

Despite representing only three months of data10, the evidence shown in Table 2 gives a good idea of the types of shifts in employment that can be expected if the job losses in certain industries - especially Leisure & Hospitality - become permanent. It also underscores the challenge and the importance of helping move unemployed Minnesotans from service-sector to non-service-sector industries and from low-skilled sectors to medium/high skilled sectors.

This study analyzed the reemployment labor market in 3rd quarter 2020. Key findings are summarized below.

In conclusion, the evidence laid out in this study gives reason for optimism about a quick recovery, but also highlights the challenges of reskilling the workforce to enable mobility from hard-hit industries to high performing ones. The same issues that hindered hiring before the pandemic - inadequate applicants' skills, inconvenient location or work hours of available jobs and jobs that don't pay a living wage - are returning. They are still preventing some unemployed jobseekers from reentering the workforce and employers from finding the talent they need. Investments in retraining, both on-the-job and through educational institutions, and employment support services, including transportation and childcare, could give workers better tools to navigate future crises.

1Other criteria for inclusion in this analysis is having filed a continuing (certified) claim, having age 18-86, being a Minnesota resident, and being employed in any of the three quarters preceding the start of the pandemic. These criteria are designed to avoid capturing individuals who filed fraudulent claims or were self-employed (PUA recipients) and who, by definition, do not have a reliable measure of reemployment in UI wage records. Some self-employed individuals could nevertheless be captured in these figures if they had some form of covered employment in the base period.

2Within Group 4, 15% stopped claiming for at least a month, indicating that they returned to work in October and then were laid off again because of mandated closures or other restrictions in November.

3Other possible explanations for not requesting benefits could be loss of eligibility, the expectation to be able to return to work very soon, or reluctance to rely on UI benefits.

4White residents in the Twin Cities were still significantly more likely to return to their previous employer than Black residents in the Twin Cities (60% versus 41%) and less likely to stay unemployed (25% versus 38%). In other words, the higher concentration of claimants of color in the Twin Cities does not explain racial disparities in re-employment patterns.

5Given UI wage replacement rules, not returning to work must have led to income losses for high earning workers even if they continued to receive UI benefits.

6Source: Profile of Risk for Prolonged Unemployment dashboard.

7The Legal group, which is very small, primarily consists of Paralegals and Legal Assistants without a four-year degree.

8We define an industry transition as a change in industry sector at the 2-digit level, keeping higher skilled sectors like Hospitals & Clinics separate from lower skilled ones like Residential Care Facilities and Social Assistance and keeping Temp help separate from the rest of Administrative Services.

9According to the Minnesota 2019 Skills Gaps Survey, one fourth (21 percent) of hard-to-fill vacancies in Manufacturing were attributable exclusively to undesirable job characteristics, including inconvenient work shifts, while 16 percent were attributed exclusively to a lack of skills, experience, or credentials in candidates (skills gaps).

10The transitions documented in Table 2 cover the period from March to September 2020. This poses two limitations. First of all, some transitions may only be temporary. Since claimants in this group (Group 3) suffered a greater reduction in hourly wages than claimants in Group 1 and 2, they may try to return to their previous jobs or switch industry again in 2021 to restore their original compensation levels. Second of all, we have no information yet about the reemployment outcomes of individuals in Group 4, who could have engaged in industry transitions in 4th quarter 2020. However, looking at the claims history of workers in Group 4 from October 2020 to April 2021 we discovered that 15% switched industry sector and then got laid off again from those newly acquired jobs. The most common industry sector of destination for claimants laid off from Leisure & Hospitality is Retail, consistent with our findings based on the smaller population of 35,673 claimants.