by Anthony Schaffhauser and Cameron Macht

September 2020

Amid this pandemic, the health care industry is on the front lines of battling COVID-19. No other industry has been as directly impacted – but health care workers have responded with courage and compassion to serve the citizens of our state. The heroism of these health care workers cannot be overstated. Doctors, nurses, therapists, aides, assistants and all health care workers continue to work and focus on other people's health, even at the risk of their own health. The value of this contribution, economic or not, is invaluable, and has served to strengthen Minnesota's fight against COVID-19.

But this battle against COVID-19 is far from over, and several new challenges are emerging, including bringing workers back to work safely, continued workforce shortages, education and certification bottlenecks, industry financial instability due to changing demand, and most importantly, the ongoing health care crisis.

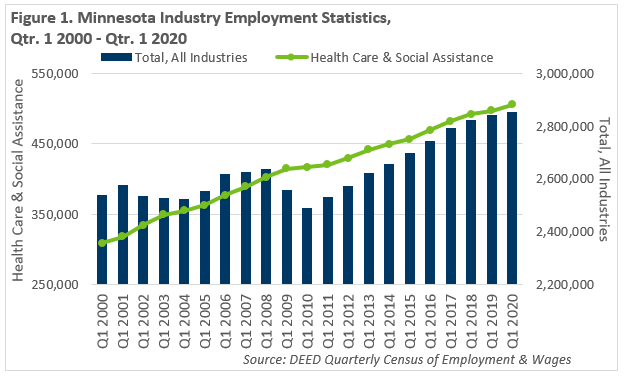

With more than 500,000 jobs in the first quarter of 2020, Health Care and Social Assistance is easily the largest employing industry in Minnesota, accounting for more than one in every six jobs in the state. It also provides the largest industry payroll, topping more than $27.1 billion in wages for workers in 2019.

Just 20 years ago, Health Care and Social Assistance provided about 313,000 jobs, accounting for 12% of total employment. It was the second largest industry at the time, with 82,000 fewer jobs than Manufacturing and only 6,000 more jobs than Retail Trade. But following major job losses and stagnation in the other two industries during the 2001 recession, Health Care and Social Assistance had surpassed Manufacturing as the largest industry in the state by 2003.

Over the past two decades, Health Care and Social Assistance has added nearly 200,000 new jobs, a stunning 64% increase, compared to 12.4% growth across the total of all industries. In sum, Health Care and Social Assistance was responsible for nearly two-thirds of the net new jobs added in Minnesota over the past 20 years, dwarfing all other industries in the process (see Figure 1).

This past growth laid the groundwork for a healthy future. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, health care was projected to be the leading source of job growth for the state over the next decade as well. While Minnesota was expected to gain just under 150,000 net new jobs total from 2018 to 2028, more than 80,000 of those jobs were predicted to be added in Health Care & Social Assistance. That would equal a growth rate of 16.5%, over three times faster than the total of all industries, at 4.7%. Accounting for 54% of the net new job growth, the forecast was that Health Care & Social Assistance would again provide the majority of new jobs in the state in the next ten years.

With an aging population and record numbers of Minnesotans with health care insurance, demand for health care services has perhaps never been higher. A report from the Minnesota Department of Health showed that health care spending had topped $47 billion in recent years, with concerns that it might double in the next ten years. The report suggested that big financial challenges to the system were on the horizon, and that efforts would be needed to limit spending increases. [1] Still, according to data from the Minnesota Department of Revenue, sales tax receipts in Health Care and Social Assistance were up more than 5.5% year-over-year on average in January and February of 2020.

Then in March 2020, the coronavirus pandemic spread through the nation and into Minnesota. Though our case numbers were relatively low, it forced major changes in the Minnesota health care system. Hospitals used the time gained during the temporary pause on non-emergency procedures to stock up on personal protective gear and other materials to prepare for a potential surge of COVID-19 patients. Health care systems stopped doing elective surgeries and other health care providers such as dentists shut down their operations to help slow the spread of the virus.

The suspension of many elective, preventative and in-person health care services caused a sharp drop in revenue. For example, an April 10 Minnesota Hospital Association news release cited an estimated $31 million per day loss to hospitals and health systems from reduced patient volumes – an estimated 55% drop in patient revenues. Overall health care sales tax receipts reflect this, declining 5% in March 2020 compared to March 2019 as the shutdown started. Receipts dropped 31.2% year-over-year in April as elective surgeries and non-emergency dental care were suspended. Receipts were still down 26.2% in May even as restrictions loosened. It is clear that Minnesota's health systems have been financially strained during this challenging time.

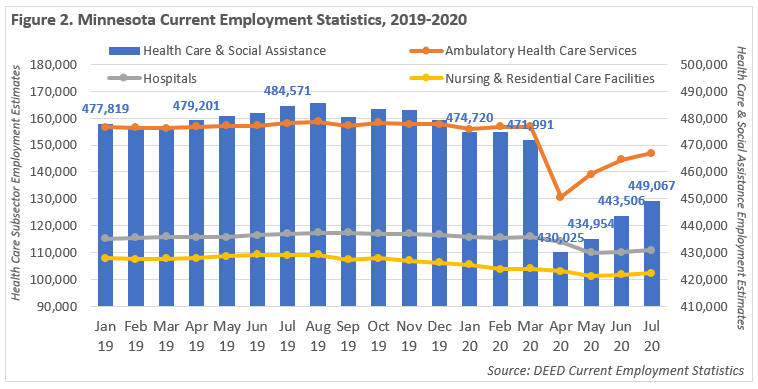

Job losses resulted from demand reductions but were not evenly distributed. Nursing homes and residential care facilities saw a decline of less than 1,000 jobs in April and were down less than 3,000 jobs in May before starting to regain jobs in June and July. By July, Nursing and Residential Care Facilities were back to 98.5% of their staffing levels prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. This short-lived employment decline can be attributed to pandemic impacts to the new worker pipeline, rather than a drop in demand. (Read more under "Obstructed Pipeline of New Workers" below.)

Hospitals were hit a little harder, but also saw a measured decline. Hospitals lost less than 2,000 jobs from March to April, but dropped by over 4,000 jobs into May as the loss of revenues from elective surgeries and lack of patients started to affect staffing levels. Hospitals have since regained about 1,000 jobs through July and are at about 96% of pre-COVID-19 employment levels.

In contrast, Ambulatory Health Care Services bore the brunt of the job losses in the industry at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. After hovering around 157,000 jobs from January of 2019 through March of 2020, Ambulatory Health Care Services abruptly sliced more than 26,000 jobs in April of 2020, a stunning 17% decline in just one month.

As clinics, doctor's and dentist offices and other health care practitioners opened back up in May, employment rebounded by nearly 8,500 jobs, then regained another 5,500 jobs in June, before creeping to just 2,400 additional jobs in July. Employment levels are still down nearly 10,000 compared to March, operating at only 94% of pre-COVID-19 staffing (see Figure 2).

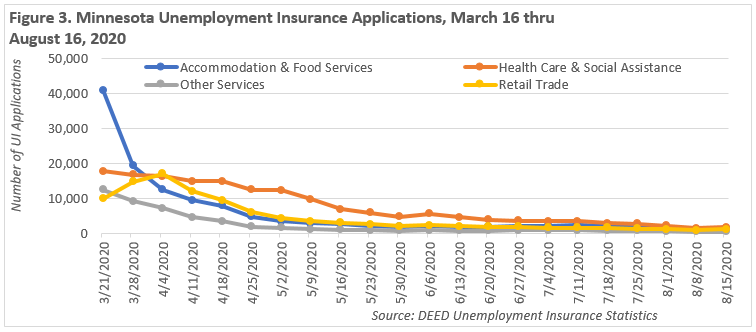

Through the middle of August, nearly 170,000 workers in Health Care and Social Assistance had filed an application for Unemployment Insurance (UI), outpacing even hard-hit industries like Accommodation and Food Services (127,000 applications), Manufacturing (107,000 applications), and Retail Trade (100,000 applications). Health Care and Social Assistance accounted for 18.5% of total UI applications, the most of any industry. That also means nearly one-third of health care workers had at least some disruption to their employment due to the pandemic.

However, the trajectory for layoffs was different for Health Care and Social Assistance than it was for these other industries. Accommodation and Food Services, Other Services, and Retail Trade all spiked within the first three weeks due to the pandemic-related shutdowns of these businesses. Accommodation and Food Services had more than double the number of UI applications as Health Care in the first week and had the most claims of any industry until the week ending May 2, when Health Care took over the top spot.

While those other three industries experienced smaller numbers of claims in May and June as many businesses re-opened, applications kept coming in from Health Care and Social Assistance. In fact, Health Care and Social Assistance even saw small week-over-week increases in new UI applications in the weeks ending June 6, July 11, and August 15 (see Figure 3). Despite the large number of applications, most were temporary layoffs as reflected in actual claims activity.

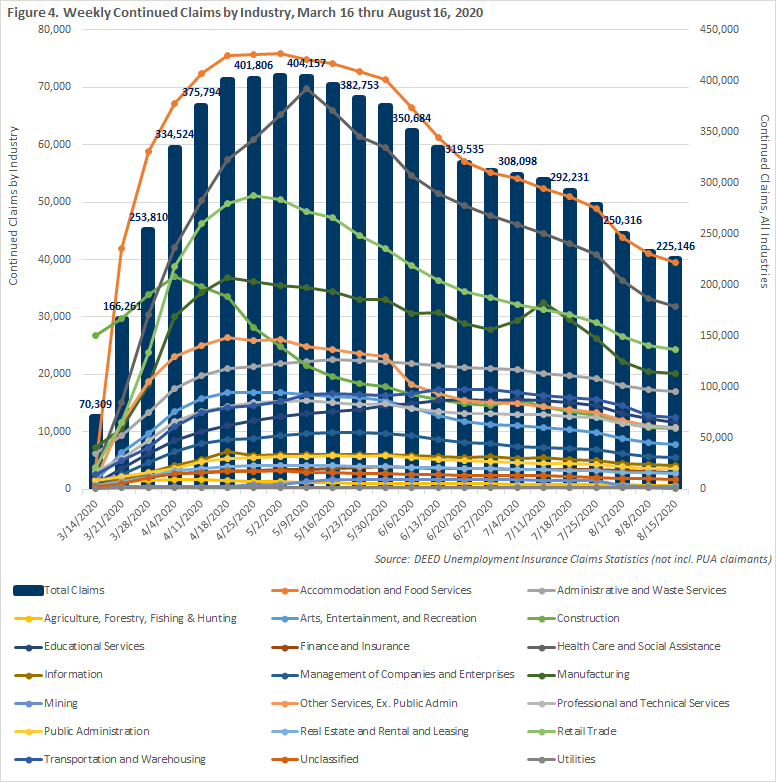

Nearly 31,000 workers in the Health Care and Social Assistance industry were still requesting weekly benefit payments through the second week of August, meaning about one in every 14 health care workers were still separated from employment. At the high point in the week of May 9, nearly 70,000 workers were filing continued claims, which was 16% of employment at that time – meaning one in every six workers was receiving UI benefits.

The only industry in Minnesota that still has more workers sidelined is Accommodation and Food Services, though both were seeing big drops in unemployed workers into August (see Figure 4). However, just 2,235 of those continued claims were filed by workers who reported the layoff to be permanent; again showing most workers expect to be called back at some point.

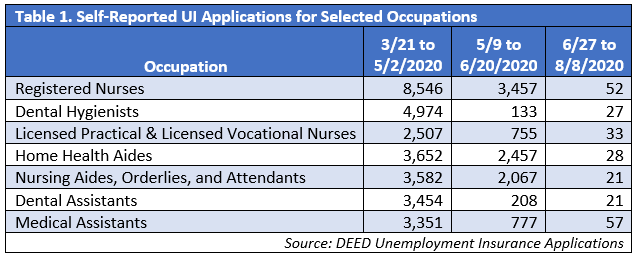

The initial wave of UI applications were filed by dental workers, occupations that have likely never had to file for UI en masse before. In the first week as dentist offices shut down across the state, nearly 6,300 dental hygienists, dental assistants and dentists filed an application for UI, accounting for just over half (51%) of all health care occupation applications in the week ending March 21. Applications dropped to 1,800 the following week and then to less than 950 in the first week of April, before dropping to a trickle from April 25 onward.

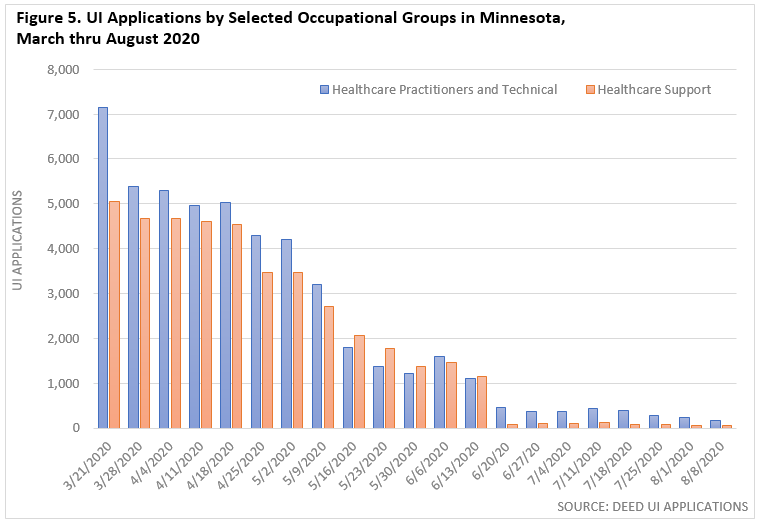

The UI activity quickly broadened to affect well-known health care support occupations, including Home Health Aides, Nursing Assistants, Medical Assistants, and all other Healthcare Support Workers. By the last week of March, one-third of UI applications were from those four occupations, and about one in every five UI applications were from health care practitioners including Registered Nurses, Licensed Practical Nurses, and other health technologists and technicians and health treating practitioners. These eight occupations accounted for half the applications in week two of the shutdown, then quickly ramped up to two-thirds of new applications from the week ending April 11 through the week ending June 13.

UI applicants self-report their occupations. Looking at those health care occupations with over 2,500 applications from March 21 to August 8, 2020 tells the story of the hit to employment at clinics and outpatient settings. It also shows that additional blows were not sustained past mid-June. By June 20, UI applications for both broad occupational classifications of health care workers had subsided. However, as noted above, a decline in new UI applicants does not mean that all those who previously applied for UI are back to work.

The pandemic also constricted the pipeline from training programs to new hires, creating challenges in filling positions in areas where demand remained - or even increased - with the pandemic. One issue is that health care education programs include required hours of clinical experiences at provider facilities. Yet, pandemic protocols and regulations precluded students from entering health care facilities. The goal was to limit exposure by limiting those interacting with patients to essential health care workers, which excludes students.

Health care education programs, their accrediting bodies, professional licensing boards, and regulating bodies continue to make changes to address the need for clinical experience and other hands-on and laboratory skill training. In the short term, most of these issues were overcome through a combination of judicious use of health care education simulations and additional new employee training. Bolstering new employee training is a task for employers, and it becomes a challenge when simultaneously addressing a pandemic. No doubt, health care employers needed to slow hiring as a result.

Most hiring was at a standstill for the three weeks between March 17 and April 6 while a modified background check process was put into place. Background checks, including fingerprinting, are required with licensing or hiring health care employees. Fingerprinting stations were closed with the March 17 peacetime emergency order to prevent COVID-19's spread. No background checks were processed until a revamped process was in place.

Specifically, the Nursing Assistant role provides a stark example of how the pandemic obstructed the new worker pipeline. There was no drop in demand, as residents of long-term care facilities continued to require care. And, in situations where residents contracted COVID-19, more care was required, while nursing assistants who contracted COVID-19 were quarantined and replacements were needed. With a short-term 75-hour minimum training program required, new nursing assistants can typically be trained and hired relatively quickly. However, at least 16 hours of the training program is student clinical experience in a licensed nursing home, which was discontinued during COVID-19 to protect residents. Furthermore, college campuses and other education settings were closed for a time, which suspended hands-on skills training.

Colleges also provide the required written and skills testing to become a nursing assistant, and their testing was postponed with the shutdown. Regulators responded on April 20 with a waiver of requirements for employed nursing assistants to pass the exam and be placed on the Nursing Assistant Registry within four months of hire. This meant that nursing assistants could be hired and work for an extended time before passing the exam. This waiver, along with the modified background checks, allowed new nursing assistants to be hired while the training and testing backlog is addressed.

The pandemic precipitated a glaring dissonance between layoffs in some settings and acute demand in others. With so many workers laid off from all industries, the focus now is to illuminate the areas where jobs are available, including through DEED's listing of current jobs in demand in Minnesota on the CareerForceMN website.

Health systems and individual facilities throughout the state have been working to reemploy laid off workers in new roles within their organizations. Likewise, the State Emergency Operations Center (SEOC) worked with the Minnesota Board of Nursing to contact licensed nurses and connect those who would switch to areas of high need with those jobs. The SEOC has also helped recruit nursing assistants who are on the registry to work at facilities with shortages.

The needs in long-term care were mentioned above, and in addition to nursing assistants, there are many roles that require skills possessed by workers laid off from accommodation and food services jobs, including culinary, housekeeping and environmental services. HealthForce Minnesota partnered with Care Providers of Minnesota and Leading Age Minnesota to launch Caring Careers Start Here with the "Let's connect now" link to connect job seekers with senior care providers who are hiring.

While hiring activity nearly stopped during April and even into May, in both June and July, Health Care Practitioners and Health Care Support Workers were among the occupational groups with the most new job postings, according to data from the National Labor Exchange. In June, there were 4,700 new postings for health care practitioners, primarily Registered Nurses; and 3,144 new postings for health care support workers, primarily nursing assistants and home health aides. Though new job postings slowed a little in July, health care practitioners were still ranked second highest overall, with health care support occupations ranking sixth.

In August, health care practitioners regained the top spot, while health care support occupations dropped to eighth place. Registered Nurses ranked number one overall, followed by Nursing Assistants in third place, Personal Care Aides in sixth place, Social and Human Services Assistants in tenth place, and Licensed Practical Nurses and Home Health Aides in 14th and 15th place, respectively.

Other occupations with a lot of postings in August include Medical Assistants, Medical Secretaries, Pharmacists, Pharmacy Technicians, and Radiologic Technicians. Hiring activity is clearly trending upward in Health Care and Social Assistance, with a wide variety of opportunities for job seekers.

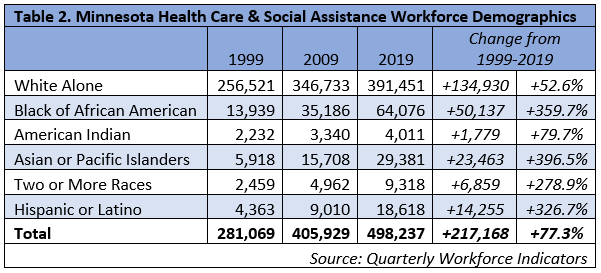

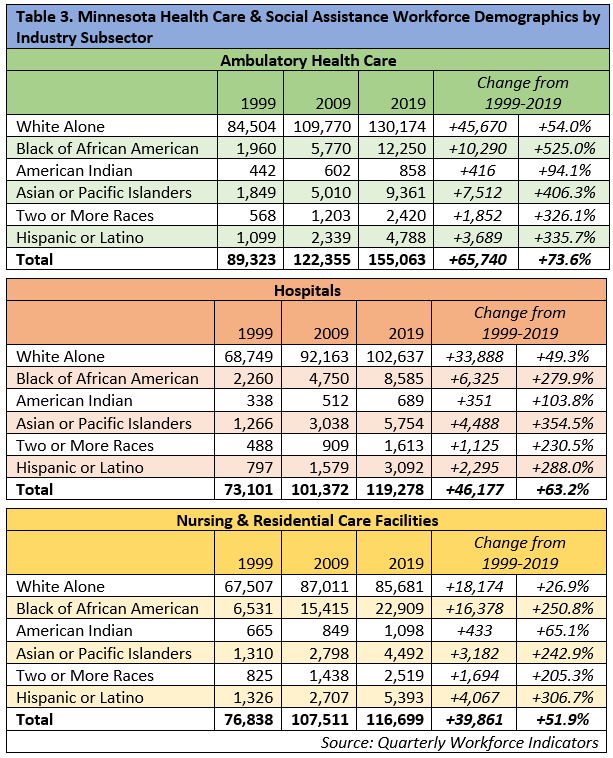

The job openings data for health care occupations are encouraging as they provide employment for Minnesota's increasingly diverse workforce. Health Care and Social Assistance is one of the most racially diverse industries in the state, and has the largest number of Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) workers of any industry. The industry went from having just under 25,000 BIPOC workers in 1999 to nearly 60,000 by 2009, and then surpassing 106,500 BIPOC workers by 2019. BIPOC workers gained more than 82,000 jobs in health care between 1999 and 2019, a 335% increase. BIPOC workers accounted for more than one-third of the job growth in Health Care and Social Assistance in the past two decades.

BIPOC workers are most likely to work in Nursing and Residential Care Facilities, and least likely to work in Hospitals. BIPOC workers accounted for more than half of the new jobs gained at Nursing and Residential Care Facilities since 1999, compared to only about 30% of new jobs at both Ambulatory Health Care Services and Hospitals. Helping BIPOC workers move into these higher-paying sectors of the health care industry is a worthwhile goal, and a smart strategy to fill these roles.

While health care employment has proven to be recession resistant in the past, it is not recession proof, and as we have shown, certainly not pandemic proof. The initial shock to health care industry employment was from the Stay at Home order. Most of this employment plunge was experienced in the Ambulatory Health Care Services sub-sector, as elective surgeries and nonemergency dental care were suspended. The short-term impact continued due to lower demand as people did not seek care to avoid exposure to infection.

The longer-term effects will be from the overall pandemic-weakened economy. People will forgo elective and non-emergency care if they cannot afford it due to cost or lack of insurance. Health care insurance coverage is often an employee benefit, which many people may have lost while they are laid off. Likewise, the recovery from the last recession revealed a drastic drop in job openings that offered health care benefits. [2] As long as the overall job market remains weak, we can expect a decline in elective, preventative and other care that can be postponed.

The pandemic is also driving changes in services that the health care industry delivers. Medical Laboratories, for example, experienced a simultaneous decrease in lab work from doctor's visits and a surge in COVID-19 testing. Telemedicine has leapt in usage, displacing in-person care. Changes like these do not necessarily mean fewer employees, but they do mean different tasks.

If demand for elective surgeries, routine and preventative care remains subdued for an extended period, workers might transition to different roles. Conversely, pent up demand for postponed care could also cause a surge in demand if risks from COVID-19 are mitigated by the development of a vaccine or more effective treatments.

In any case, the job openings data above reveal health care remains a field with large numbers of job openings. While the pandemic's impact on long-term projected employment is unknown, even if growth in health care employment slows it will still likely outpace the growth in all industries.

Anthony Schaffhauser is the Statewide Director of Healthcare Workforce Development for HealthForce Minnesota, and Cameron Macht is the Acting Assistant Director and Regional Analysis & Outreach Manager for the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development Labor Market Information Office.

[1] Minnesota Department of Health.

[2] Casale, Oriane. "Recession Takes a Toll on Health Care Benefits." Minnesota Economic Trends. March 2010.