Summarized by Oriane Casale

March 2024

A series of new reports, commissioned by the Minnesota Departments of Education and Human Services in partnership with the Children's Cabinet, and conducted by Wilder Research, explores the characteristics of the early care and education (ECE) workforce, assesses educators' economic well-being, and describes their participation in training and professional development opportunities.

Data for the reports was collected through a survey and focus groups with Minnesota ECE educators. In total, 1,050 educators responded to a mail-push-to-web survey of a randomly selected sample of educators in a variety of public and private settings across the state.

This summary provides high-level findings from the reports. The reports can be accessed at the Wilder Foundation website and are authored by Jennifer Valorose, Sera Kinoglu and Amanda Petersen of the Wilder Foundation.

The researchers identified 9,327 programs across Minnesota serving children in a child care capacity served by an estimated 40,000 early educators. Programs include licensed child care centers, licensed family child care providers, Head Start and Early Head Start programs, license-exempt (both certified or uncertified) child care programs that serve children prior to kindergarten entry, public school districts and charter schools offering early learning programs.

On average, centers had 14 staff. School-based programs had a slightly higher number of employees, 17 staff. Annual turnover is 30% overall and highest among aides at 38%. A majority of the surveyed educators (63%) work full-time hours, between 31 and 50 hours per week, with licensed family child care providers and program directors averaging more hours per week than other staff.

Survey respondents largely identified as white alone (92%) and as women (98%) with an average age of 44. U.S. Census data indicates that this workforce in Minnesota is likely more racially and ethnically diverse and that there are more males working in the field than is reflected in survey responses.

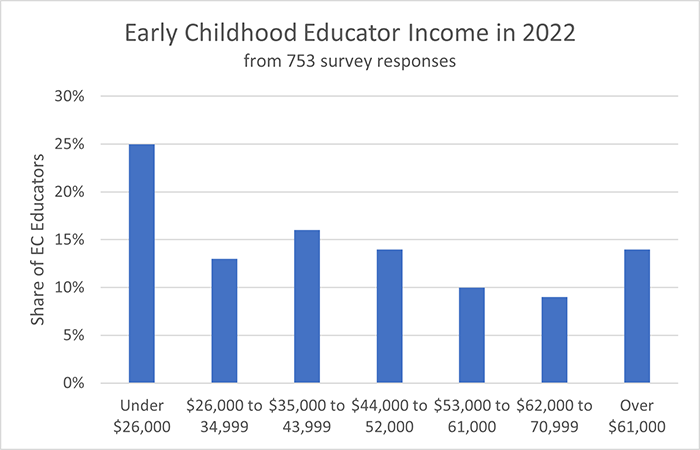

Based on 755 survey responses, about 25% of ECE educators earned less than $26,000, with over half (54%) earning less than $44,000. At the other end, 14% of ECE educators earned over $61,000 per year. Looking at total household income, 16% of the workforce is living below 200% of the federal poverty level (higher in Greater Minnesota at 21%) and 15% rely on public benefits, primarily Medical Assistance.

From Table 7: Income from early care and education job in 2022, page 15.

Directors were asked which benefits their ECE program offers. The majority offer paid time off (86%), employer-provided training (76%), reimbursement for training expenses (56%), retirement plans/401K (52%), medical insurance (51%) and discounted or free child care for employees' children (51%). Fewer than 50% offered other benefits like dental and paid parental leave.

From the employee side, 86% report being covered by a health insurance or medical plan (compared to 95% of residents under age 65 in Minnesota). Of the total, 49% report being covered through their ECE employer, with 37% through a family member or another job. In addition, 11% bought insurance directly, mostly through MNSure, and 9% were covered through public insurance, mostly Medical Assistance and Medicare.

Licensed family child care providers were most likely to be covered by their family member's employer or through MNSure, while school-based educators were most likely to be covered through their ECE employer. Thirty-three percent of licensed center staff were covered through their ECE employer (Table 10, page 18).

Survey results show that educational requirements vary by role and type of program. School-based program staff are most likely to have an associate degree or higher (94%), in part because of the requirements of these public programs. In licensed centers, 75% of staff have an associate degree or higher. Among licensed family child care educators, 41% had an associate degree or higher.

Based on survey findings, the ECE workforce has many years of experience in the field. Licensed family child care providers have the most experience working in ECE programs at 22.6 years on average. Directors have 19.4 years, teachers have 15 years, assistant teachers have 8.5 years, and aides have 5.5 years of experience. All of these groups report planning to stay in the field for a decade or more, on average.

Early childhood educators have many opportunities for formal and informal professional development, and, based on survey results, many are interested in increasing their level of education. This is particularly true in license-exempt and Head Start programs, where more than half reported being interested in increasing their level of education.

Overall, 96% of the ECE workforce reported having "at least one other professional caregiver you can talk to for support or get advice from," and 44% reported participating in relationship-based professional development in the past year.

Many professional development resources are available, with Develop Minnesota the mostly widely used resource, particularly among licensed family child care providers and staff at licensed child care centers and Head Start/Early Head Start programs. ECE educators are generally satisfied with the professional development resources they have used and find them helpful. The top support that ECE educators needed to participate in professional development was paid time off to participate, followed by virtual opportunities and funding or scholarships.

Burnout was a common experience among the focus group participants. Staffing challenges were even more commonly mentioned, particularly the lack of support staff and substitutes. These issues impacted staff's ability to take breaks, the feeling of being overwhelmed, higher child-to-staff ratios and less support overall.

Financial stress was another issue commonly cited, especially in centers. Lack of health insurance exacerbated this burden. Finally, a lack of respect for their profession was also cited as a challenge in the field of ECE.

To overcome these challenges, ECE educators cited connections with colleagues as well as formal supports such as professional learning communities. Moreover, a love of teaching young children and seeing them develop, as well as a desire to support the children's families, helped to keep them in the field.

This article is a summary of Minnesota's Early Childhood Educators 2023 Statewide Study of the Demographics, Workforce Supports, and Professional Development Needs of the Early Care and Education Workforce, by Jennifer Valorose, Sera Kinoglu, and Amanda Petersen, released December 2023 by Wilder Research. This report, along with targeted report summaries can be found at the Wilder Foundation Early Care and Education Workforce, 2023 Study).