by Shawn Herhusky and Carson Gorecki

September 2020

In recent conversations with businesses, the same question keeps coming up: where are the job seekers? Many employers in industries such as Hospitality, Retail, and Food Service are desperate for staff at a time when the regional unemployment rate is at 8.4% (July 2020), lower than the last few months but still 3.3 points higher than in February 2020. This 8.4% unemployment rate in northeastern Minnesota represents over 13,500 unemployed workers – nearly double the number of active job seekers in March 2020. Employers should be able to find workers with so many people on the sidelines.

Part of the confusion stems from the commonly accepted idea that there would be a rush of new job seekers following the end of the temporary Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) $600 Unemployment Insurance (UI) benefit. However, recent research from Yale, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), and Gallup indicate that, on average, workers who were receiving the additional $600 benefit were as likely to return to work as those who were not.

First, a Yale study titled Employment Effects of Unemployment Insurance Generosity During the Pandemic, found some fascinating new correlations utilizing data from Homebase, a firm that provides scheduling software to small businesses.

According to the Yale study:

The workers who experienced larger increases in UI benefits relative to their previous income did not experience larger declines in employment when the benefits expansion went into effect.

Workers facing larger expansions in UI benefits have returned to their previous jobs over time at similar rates as others.

The Yale Study found no evidence that the enhanced unemployment insurance benefit disincentivized work either at the onset of the expansion or as firms looked to bring workers back or hire more workers as business restrictions were lifted. Yale researchers were careful to note that additional research must be done after businesses had increased operations after restrictions were lifted. The Yale research relies on data through mid-May, so conditions may have changed.

The authors of the NBER paper take a slightly different approach. By incorporating factors in addition to just unemployment benefits and job wage levels, they are able to capture more of the complexity in the choices facing unemployed workers. The authors weigh these added factors: how long the UI benefits are expected to last; how likely it is that the employee’s job will be available to return to over time; how likely they are to experience a decrease in wages if they were to take a different job; and how hard it might be to find a new/different job.

One of the assumptions underlying these questions is that there exists a basic choice between staying on UI or returning to the job they were laid off from. In Minnesota, if a worker refuses a call back by their employer, they risk losing their unemployment benefits. The choice is effectively made for unemployed Minnesotans. Nevertheless, there are still findings relevant to Minnesota in the NBER paper. Particularly, that workers consider potential longer term impacts and tradeoffs such as the likely decrease in income that comes with switching jobs. Unemployment benefits have limited terms and as we have seen, it is uncertain whether supplemental benefits will be extended by policymakers. Similarly, open positions and offers have shelf lives. The results of the study imply that workers consider a job to be a better and more secure provider of income than temporarily enhanced unemployment benefits.

Finally, Franklin Templeton and Gallup polled Americans on stimulus payments and unemployment benefits as responses to the current economic crisis. One of the questions focused on participants likelihood of returning to work given different enhanced UI benefit amounts of $150, $300, and $450. “The vast majority of respondents indicated a desire to return to work, and their willingness to do so varied little when they were presented with different hypothetical levels of additional federal unemployment benefits.” Granted, Gallup did not include the $600 amount that was actually implemented, which, if included may have altered participants’ responses. However, the results show that, in general, more generous UI benefits do not disincentivize people from returning to work.

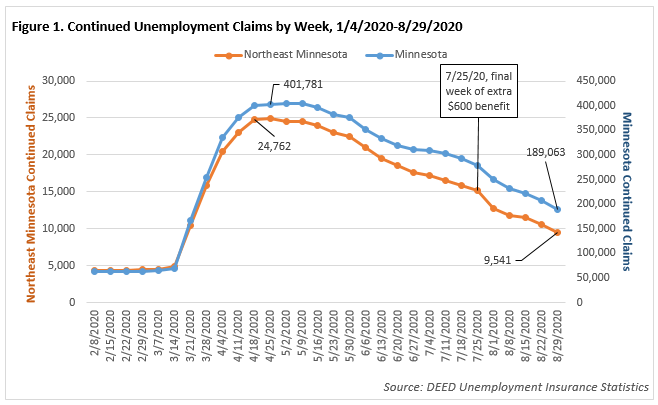

Anecdotally, the DEED team in Northeast Minnesota had also been hearing that the UI benefit was a disincentive and making it more difficult to hire. But even after the additional $600 a week FPUC benefit ended, local businesses still seem to be having trouble finding the talent they need to be successful. If the major roadblock was in fact the extra $600 payment, its ending on July 25 should have opened the floodgates of talented Minnesota workers looking for their next opportunity. So far, employers report that it hasn’t happened. Why not?

Based on conversations with and background from regional employers, the authors would like to focus on three possible explanations:

Part of the reason might be employers calling back their existing workforce. As explained above, UI benefits should end once the employer recalls their employees, whether they accept the offer or not. In July, only 5.9% of claims in Northeast Minnesota were reported as permanent indicating that the vast majority of claimants still expected their unemployment to be temporary. Workers who are waiting to be called back to their old job might not be interested in looking for something else. The NBER study addressed this issue by incorporating the potential decrease in wages from switching jobs in their model.

Another reason could be health and safety concerns related to the continuing COVID-19 pandemic. Older workers and individuals who live or work with populations especially vulnerable to the virus may be electing to stay home until the virus threat is reduced. Likewise, workers in customer-facing occupations particularly in the leisure and hospitality, retail trade, educational services, and health care and social assistance industries may be waiting to return until they feel safer. Interestingly, the regional labor force has shrunk 2.3%, or almost 4,000 workers, since February as some workers decided to stop looking for work or retire. Northeast is the only region in Minnesota where the labor force shrunk during the summer months, creating a tight labor market despite the high unemployment rate. And while the number of unemployed fell 2,921 from June to July, employment increased only 524 over the same period. The number of people leaving the labor force altogether seems to support the notion that, at least for some, enhanced benefits are not the prevailing factor in workforce decisions.

A third option could be that individuals were waiting to see if an additional stimulus check or enhancement to unemployment benefits were going to be implemented. In this case, the temporary Lost Wages Assistance (LWA) Program was created by presidential memorandum on August 8 and Minnesota’s request for funding was approved August 29. DEED’s UI office made six weeks of payments to Minnesotans determined eligible for the temporary federal LWA payments. These payments were for six weeks of unemployment: the week beginning July 26 through the week beginning August 30, after which the temporary federal funding ran out. At the time of writing, Congress has debated additional supplemental federal unemployment assistance as part of a larger stimulus package, but it is unclear when or if that will move forward.

It’s difficult to predict what’s going to happen next with labor force participation. The number of COVID-19 infections continue to rise in Northeast Minnesota, which may be a disincentive for some populations to return to work. Some workers appear to be leaving the labor force altogether. Finally, we do not know what additional stimulus or enhanced UI benefits might be coming from Washington. However, what we do know is that, in general, it does not appear that supplemental benefits are deterring the unemployed from returning to work. There are many factors to consider and enhanced unemployment benefits are one piece of an increasingly intricate puzzle.

Links: