by Oriane Casale

March 2019

As a result of continued steady job growth since the end of the Great Recession in 2010 and slow to no labor force growth primarily caused by an aging population, there are now fewer unemployed workers than vacancies. Minnesota’s unemployment rate, at 3.2 percent in March 2019, is very low by historical standards and is 13th lowest nationwide.

Largely from retirements, the labor force participation rate dropped to 69.8 percent in 2018, the lowest it’s been since 1981. As a result, employers across the state and its diverse industries are having a difficult time finding workers, managing turnover, and remaining fully staffed. This in turn is slowing the overall growth of Minnesota’s economy.

The early learning industry both impacts this picture and is impacted by it. Young families need child care in order to work, and many will choose not to work rather than place their young children in low quality or unaffordable care. On the flip side early learning programs are having difficulty hiring and retaining qualified workers, which is impacting access to and quality of care. Program closures are impacting rural areas of the state most dramatically, but child care deserts exist in urban areas as well.

Early learning programs in Minnesota include publicly funded programs – Head Start and pre-k classes in public schools – as well as private and nonprofit businesses. These include both family child care programs and child care center based programs. According to a recent Department of Human Services study, there are 43,000 employees in the early learning industry in Minnesota with about 35,500 of these employees in private and nonprofit programs. This article focuses on these private and nonprofit programs.

Most of these private and nonprofit early learning programs are small private businesses with most family child care providers self-employed. The average staffing in a center-based program is 14 employees and in a family child care home is 1.3 employees.

Wages are very low in early learning occupations. Most of the cost of running a center comes down to staffing but centers have a difficult time raising prices enough to adequately compensate staff. Infant classrooms, for example, require a minimum of two full-time equivalents for eight children and are generally open a minimum of 10 hours a day to accommodate parents work/commute schedules. Even at an average cost of $16,000 a year per infant (statewide 2017, Child Care Aware Minnesota), it is difficult to see how anyone could put together a viable business model for this age group.

Table 1 provides 2018 wages in Minnesota’s early learning programs. Wages for preschool teachers, who are required to have a related associate’s degree in most private centers, are critically low in private ownership settings and much lower than those in publicly funded settings. Wages for child care workers are also critically low compared to other occupations that require a high school diploma.

Based on DEED’s cost of living calculator the basic cost of living for a single person ranges from $12.85 an hour in southwest Minnesota to $15.69 an hour in the Seven County Twin Cities Metro region. Since child care wages do not sustain a basic cost of living, it is difficult to recruit and retain qualified workers in the industry.

| Table 1. Wages for Minnesota's Early Learning Industry | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation | 25th Percentile | Median | 75th Percentile |

| Education Administrators, Preschool and Child Care Center/Program | $20.50 | $24.60 | $31.72 |

| Preschool Teachers, except special education | $12.95 | $15.03 | $25.81 |

| Private ownership | $12.86 | $14.68 | $17.68 |

| Public ownership | $16.60 | $21.57 | $28.49 |

| Child Care Workers (public and private settings pay similar wages) | $9.97 | $11.44 | $13.89 |

| Source: Occupational Employment Statistics | |||

These low wages negatively impact the pipeline of workers coming into this industry, creating a critical talent gap. Based on Statewide Longitudinal Education Data System (SLEDS) data, private and non-profit sector wages clearly do not justify the financial burden of obtaining a degree in the field and do not support the cost of repaying loans.

In Minnesota graduates with an Associate Degree in early learning or child development earned a median wage of only $13.90 in center-based child care programs two years after graduation. Those with a Bachelor's degree in early learning or child development who worked in center-based programs earned a median wage of only $15.60 while those who worked in elementary or secondary schools earned $24.40 two years after graduation. Because of the large earnings gap, most graduates with Bachelor or graduate credentials end up pursuing jobs in public schools, leaving private and non-profit child care programs bereft of highly trained teachers (see Table 2).

| Table 2. College Workforce Pipeline, 2011 to 2015 Graduates, Minnesota | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree | Industry of Employment | Number Employed | % Employed in Industry | Median Wage Second Year After Graduation |

| Certificates | Elementary and Secondary Schools | 64 | 16.2% | $ 14.20 |

| Certificates | Social Assistance (private center-based) | 155 | 39.3% | $ 13.20 |

| Associate Degree | Elementary and Secondary Schools | 145 | 16.4% | $ 14.40 |

| Associate Degree | Social Assistance (center-based programs) | 402 | 45.5% | $ 13.90 |

| Bachelor's Degree | Elementary and Secondary Schools | 287 | 58.5% | $ 24.40 |

| Bachelor's Degree | Social Assistance (center-based programs) | 101 | 20.6% | $ 15.60 |

| Graduate Degree | Elementary and Secondary Schools | 109 | 64.1% | $ 32.20 |

| Graduate Degree | Social Assistance (center-based programs) | 29 | 17.1% | $ 21.00 |

| Source: Graduate Employment Outcomes Tool | ||||

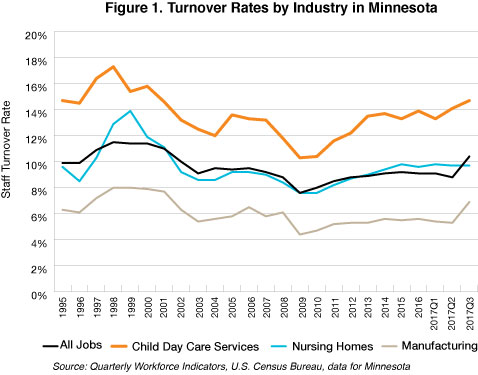

This talent gap is being compounded by high turnover in the industry. Figure 1 shows that the Child Care Services industry has higher turnover than most other industries in Minnesota.

Turnover further exacerbates staffing shortages and negatively impacts program quality. It has been well established that young children are better able to play, learn, and thrive in a stable environment where they can develop attachments with the important adults in their lives. Staff turnover negatively impacts stability, causing stress and slowing learning in young children.

Moreover, from a business perspective, high turnover increases costs to programs that must continually hire and train new staff. In these small businesses, many of which barely make ends meet financially, the cost of turnover can make the difference between staying in business and going out of business. Turnover is an even bigger challenge in rural regions of the state (see Table 3).

| Table 3. Turnover Rates in Child Day Care Industry by Region, 2016 | |

|---|---|

| Region | 2016 |

| Duluth MSA | 13.7 |

| Mankato MSA | 13.6 |

| MSP MSA | 13.7 |

| Rochester MSA | 13.0 |

| St. Cloud MSA | 14.2 |

| Rural Counties (non-MSA) | 15.0 |

| Northwest (1) WSA | 11.7 |

| Rural CEP (2) WSA | 17.0 |

| Northeast (3) WSA | 14.5 |

| Southwest (6) WSA | 15.0 |

| South Central (7) WSA | 15.5 |

| Southeast (8) WSA | 12.8 |

| Source: Quarterly Workforce Indicators, U.S. Census Bureau, data for Minnesota | |

With vacancy rates of 5.7 and 10.3 percent compared to 5.2 percent across all occupations, labor market demand is higher than average for both preschool teachers and child care workers (see Table 3). Wage offers mirror the wages of currently employed workers in the industry including the gulf between the public and private sectors, especially for preschool teachers. The median wage offer for preschool teachers in public and private settings combined is $20.82 compared to the median wage offer for preschool teachers in center-based programs at $14.31. Wage offers are somewhat lower in Greater Minnesota at the median than in the Seven-County Twin Cities area.

The median wage offer for child care workers, who generally do not need post-secondary education to work in public or private programs, is $12.45.

Based on DEED's Occupations in Demand data series, updated annually, demand for child care workers ranks 56th out of 315 occupations, making it a high demand (top quintile) occupation. With a high school diploma required for most of these job openings, this occupation is at the very bottom of median wage offers within its educational requirement category among other high demand occupations (see Table 4). Moreover, with high turnover and high demand in the occupation, we project that the industry will have to fill 44,000 jobs by 2026.

| Table 4. Minnesota Job Vacancies in the Early Learning Industry, Second Quarter 2018 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation | Number of Vacancies | Median Wage Offer | Vacancy Rate | Percent Requiring Postsecondary |

| All Job Vacancies | 142,282 | $14.54 | 5.2% | 31% |

| Preschool Teachers | 436 | $20.82 | 5.7% | 100% |

| Preschool Teachers – private ownership | 214 | $14.31 | NA | 100% |

| Twin Cities | 139 | $14.49 | NA | 100% |

| Greater Minnesota | 74 | $13.23 | NA | 100% |

| Preschool Teachers – public ownership | 222 | $24.88 | NA | 100% |

| Child Care Workers | 1,189 | $12.45 | 10.3% | 15% |

| Source: Job Vacancy Survey (JVS), DEED | ||||

Likewise preschool teachers rank 79th overall, also a high demand (top quintile) occupation. With a related Associates Degree required, preschool teachers are also at the very bottom of median wages in their educational requirement category.

While the wages in the early learning industry are too low to make these employers eligible for many of the training and retraining programs that the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development offers1, Minnesota has several workforce development programs to support the industry and its employees.

The Community Child Care Expansion Grant Program provides funding to implement solutions to reduce the child care shortages in the state, including but not limited to funding for child care business start-ups or expansions, training, facility modifications or improvements required for licensing, and assistance with licensing and other regulatory requirements. At $500,000 a year, this program created or retained 1,159 early learning slots in SFY 2018, primarily in Greater Minnesota.

Other programs that support staff and reduce turnover are the Retaining Early Educators Through Attaining Incentives Now (RETAIN), which provides a competitive bonus system to help keep well-trained child care professional in the field. Recipients make a commitment to remain in their position or business for at least one year after the grant is awarded. Since 2003, RETAIN has awarded bonuses to over 2,000 professionals degreed or credentialed in early childhood and school-age care.

TEACH Scholarships help early childhood and school-age care providers increase their levels of education by providing reimbursement to center-based or school-age care staff for credits toward an Associate's or Bachelor's Degree in Child Development or Early Childhood Education at an accredited Minnesota college or university. All together 903 students have received a TEACH scholarship since the program's introduction in 2002.

Together these programs help support the industry and its employees, but at current funding levels can only begin to address quality, access, and the problem of program closures in Minnesota.

To the extent that early learning programs can mitigate later learning disparities in grade school and beyond, it is important to ensure that all programs in Minnesota provide high quality care that allows young children to thrive. The current picture of low wages, resulting in a talent gap and high turnover rates, negatively impacts the quality of Minnesota's private early learning programs. Moreover, the resulting shortage of child care slots is limiting parents' ability to participate in the labor market, particularly in Greater Minnesota, and further driving down already historically low labor force participation rates in Minnesota.

1The Minnesota Job Skills Partnership program, for example, has never partnered with a child care establishment because the wages do not meet the definition of "living wage".