by Anthony Schaffhauser

March 2023

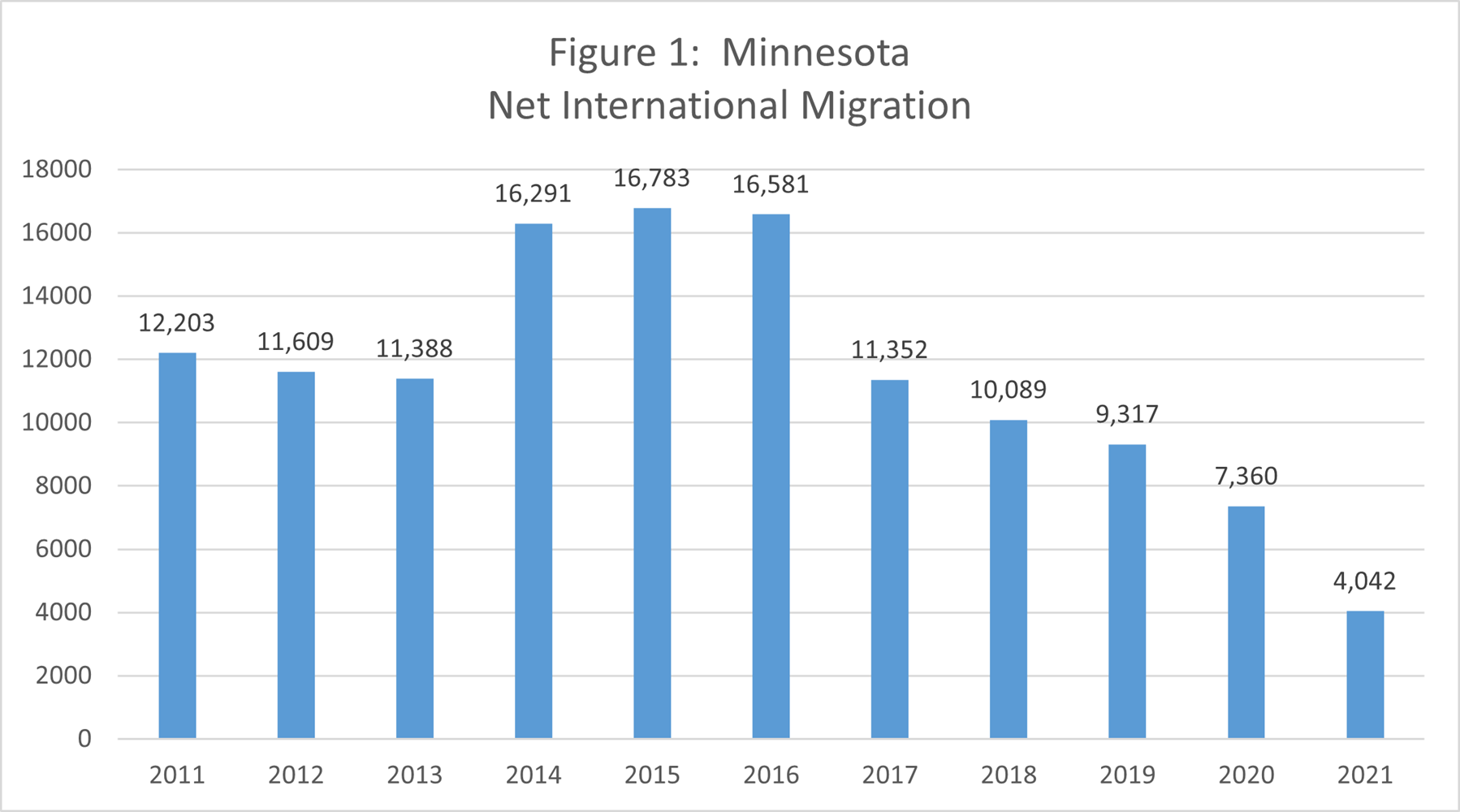

The defining feature of 2022's labor market was record tightness. Minnesota reached its all-time record low unemployment rate of 2.3% in April. That's the lowest rate ever recorded in Minnesota, dating back to 1976 when such data started being tracked at the state level. With that tight of a labor market, workforce and economic development partners are exploring ideas to help build Minnesota's labor force back up again. Looking at population trends, it is remarkable that reversing our state's international immigration declines would get us over 25% of the way back to pre-pandemic labor force trends. Net international immigration has been trending down since 2015, and it drastically dropped from 2020 to 2021 during the pandemic. (See Figure 1.)

With a total of over 3 million Minnesota workers, at first glance these immigration numbers – which hover between 4,000 and 17,000 per year – seem entirely too small to impact our state's labor force. However, examining the underlying demographics driving the exceptionally tight labor market, we can make some "back-of-the-envelope" calculations to determine if reversing the immigration declines experienced since 2015 would have an appreciable impact. This analysis also provides insight into the relative impact of the pandemic versus longer-term demographic trends.

Those who study our state's demographic and labor force trends have been talking about the tightening labor market created by our aging population for over a decade. The supply of workers was set to decline as the Baby Boomers aged, and Minnesota's labor market has a larger share of Boomers than other states. According to generational definitions, Boomers were aged 56 to 74 in 2020, about 22.5% of Minnesota's labor force in 2020, compared to 21.5% for the entire United States.

| Table 1: Calculation of Regaining Immigration Impact | ||

|---|---|---|

| Label | Estimate | Description |

| A | 75,687 | Pre-pandemic Projected 2020 to 2030 Labor Force Growth1 |

| B | 191,984 | Actual 2010 to 2020 Labor Force Growth (Change in Average Annual Labor Force)2 |

| C=A-B | -116,297 | "Slowed Labor Force Growth" |

| D=A/10 | 7,569 | "Expected Annual Labor Force Growth," 2020 to 2030 |

| E=(A-B)/10 | -11,630 | "Expected" Annual Slowed Labor Force Growth |

| F | -93,060 | Labor Force Change 2020 to 20212 |

| G=F-D | -100,629 | 2021 "Worker Shortfall" from Projected |

| H | 37,697 | Labor Force Change 2021 to 20222 |

| I=H-D | 30,128 | 2022 "Greater-than-Projected" Worker Gain |

| J=F+I | -70,500 | 2022 "Pandemic-Induced Worker Shortfall" |

| K=J/8 | -8,813 | Annual "Worker Shortfall" through 2030 |

| L | 107,830 | Net Immigration 2010 to 2018 (see endnote) |

| M=L/8 | 13,479 | Assumed Annual Net Immigration in Pre-Pandemic Projections |

| N | 16,783 | 2015 Net Immigration (from Figure 1) |

| O=N-M | 3,304 | Annual Net Immigration Increase (if restored to 2015 level) |

| P | 93.3% | Share of MN Foreign-Born Population Age 15 and Older3 |

| Q=O*P | 3,082 | Additional Immigrants Aged 15 and Older |

| R | 69.2% | LFPR for Age 16 and Older MN Population3 |

| S | 3.8% | Percentage Points Higher LFPR of Foreign-Born MN Residents (article linked in text) |

| T=Q*(R+S) | 2,250 | Estimated Additional Workers from Restoring Immigration to 2015 Level |

| U=|T/K| | 25.5% | Portion of Pandemic-Induced Worker Shortfall Reversed by Restoring Immigration |

| 1DEED calculations based on Minnesota State Demographic Center 2020 Population Projections and U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey 2015 to 2019 estimates | ||

| 2MN DEED Local Area Unemployment Statistics (Seasonally Adjusted) | ||

| 3U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 5-year estimates, 2017-2021 | ||

As a result, Minnesota's labor force growth was already projected to slow by 116,297 workers or –60.6% from 2020 to 2030 compared to 2010 to 2020. We were still expected to add over 75,000 workers in the next decade, but that was much slower than the previous decade. (See Table 1 to follow along with the numbers and calculations in the text. C = "Slowed Labor Force Growth.") This projection is based on the 2020 to 2030 population projections produced in 2019 and the labor force participation rates (LFPRs) by age from 2015 to 2019. Therefore, it is based on the pre-pandemic trends. In other words, Minnesota was expected to add an average 7,569 workers per year to the labor force from 2020 to 2030 if the pandemic had not happened (Table 1, D = Expected Annual Labor Force Growth). This is compared to the average 19,198 per year labor force gain from 2010 to 2020, yielding an expected annual average slowdown in labor force growth of 11,630 workers per year, even if the pandemic did not happen (E). A lot of labor market tightening was set in motion prior to the pandemic.

From 2020 to 2021 we saw a loss of 93,060 workers (F), compared to the projected annual gain of 7,569 (D). Combining these produces a roughly 100,629 worker shortfall below what was projected (G). Fortunately, from 2021 to 2022 the labor force sprung back, growing by 37,697 workers (H). Less the 7,569 average annual projected growth, that leaves a greater-than-projected gain of 30,128 workers for 2022 (I). Thus, by the end of 2022 the pandemic-induced shortfall was reduced to 70,500 workers (J = 100,629 less 30,128). So, we are short roughly 8,800 workers per year through 2030 (K = 70,500/8). In other words, we just need to add an additional 8,800 workers per year for the remaining eight years until 2030 to be back to the pre-pandemic trend. Where do we get an additional 8,800 workers per year? What if immigration increased to its 2015 level?

To estimate the impact of increasing immigration to its 2015 level, we want to estimate the incremental gain over the immigration that was included in the 2020 to 2030 population projections. We do not want to double count the immigration that is already included in the pre-pandemic projected population growth. Instead, we want to know what would be gained beyond that. Let's conservatively assume that the population projections incorporate the same annual net immigration change over the eight years from 2010 to 2018 of 107,8301. That is 13,479 annually (M), or 3,304 fewer immigrants than in 2015. So, if Minnesota replicated 2015 immigration levels, it would provide an additional 3,300 people per year (rounding O = net immigration less that included in the population projections).

Over 93% of Minnesota's foreign-born population is age 15 or older. So, the 3,300 additional immigrants would provide about 3,080 people aged 15 years or older (rounding Q). We also know from previous research that foreign-born residents participate in the labor force at a 3.8% higher rate than U.S.-born residents. If we apply that to the 69.2% LFPR for the entire age 16 and older population in Minnesota, these 3,080 working-age immigrants would add 2,250 workers per year (T = 3,080 x 73% LFPR; LFPR for this article is from the American Community Survey because it provides estimates specific to foreign-born residents).

If we need 8,800 workers per year to get labor force growth back on track to pre-pandemic levels, gaining 2,250 immigrant workers each year would resolve over 25% of the pandemic-induced labor force decline (U = 2,250 additional immigrant workers per year divided by the 8,800 needed to get back to pre-pandemic trend).

Of course, that would still leave us short 6,550 workers per year. However, that is 56% of the 11,630 annual decline from slower labor force growth compared to the prior decade. Thus, in addition to showing the impact of restoring immigration, this analysis also shows the relative impact of the long-term demographic trends driven by an aging population compared to the short-term impact of the pandemic.

Specifically, this analysis shows a 116,297 reduction from slowed labor force growth compared to a 70,500 reduction from the pandemic, acknowledging the fact that the pandemic reduction happened in one year rather than over ten years. The potential solutions are the same whether from long-term or short-term impacts, namely strategies to increase net migration (international and domestic) and labor force participation.

1The 107,830 Minnesota net international migration 2010 – 2018 is from Minnesota State Demographic Center (October 2020), Long-Term Population Projections for Minnesota, Table 5 (page 6). The source is the 2018 vintage Census Bureau Estimates Program data tables, and these differ from the updated vintage 2020 and vintage 2021 net immigration presented in Figure 1 of this article.

The 107,830 estimate is conservative because the projections incorporate a trend of slowing international migration. "This slower rate of [population] growth can be most generally attributed to changing assumptions for the impact of the various components of change—most importantly, declining rates of international migration." (page 11) While population projections are based on " . . . historical trends in births, deaths, and international migration . . ." (page 6), the projections do not actually use a net international immigration estimate. Birth rates, death rates, and aging are used to project the population, along with total net migration, both domestic and international combined. Therefore, I must assume an immigration estimate for this analysis. I chose to use past immigration, which somewhat understates the gains from restoring immigration to 2015 levels.