by Mustapha Hammida

December 2020

The arrival of the virus that causes COVID-19 in Minnesota in early 2020 and subsequent steps to slow its spread sparked immediate and severe widespread economic damage. Although several aggregate statistics describe the magnitude of this damage, many details on the impact on businesses and industries have been missing from the picture.

Between March and May, the state’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate leaped from a near historic low of 2.9% to an unprecedented high of 9.9%. In April, the labor force participation rate, or the percentage of the working age population that is either working or actively looking for work, declined to a low of 68.9% not seen since, coincidentally, the same month of 1979. In addition, by April, employers cut 13% of their jobs, resulting in a decline from 2,977,600 jobs in February to 2,589,800 in April.

These sharp drops in the labor market emerged out of efforts by state government, businesses, and consumers to slow the spread of the coronavirus and allow the health care sector to staff and equipment people seriously ill with COVID-19. As a result, many businesses reduced jobs or closed altogether either in compliance with various executive orders or in response to declining demand for their goods and services.

This study provides an in-depth look at the immediate impact of COVID-19 on Minnesota businesses by analyzing data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) program. It compares the net job loss during the COVID-19 recession to the previous two recessions, quantifies the impact of COVID-19 on businesses during March and April 2020, and evaluates the initial extent and duration of business closures due to COVID-19.

This study analyzes the monthly employment at each Minnesota establishment from the QCEW microdata. The QCEW defines monthly employment as the count of workers who worked for an establishment during, or received pay for, the pay period that includes the 12th day of the month. Thus, it is a “snapshot” measure of employment at a point in time of the month. An establishment, or a business, represents a single physical location where goods and services are produced.

All establishments covered under the Unemployment Insurance Program are required to report wage and employment statistics quarterly to the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development (DEED). The QCEW program is a census of Minnesota businesses that covers 93-97% of jobs. Some excluded jobs include those held by certain farm and domestic workers, self-employed people, railroad workers, and elected officials.

The U.S. economy officially entered a recession in February 2020, according to the Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Once a business cycle is dated, a recession is defined by the period between a peak of economic activity and its subsequent trough. To compare the difference between peak and trough employment levels in the 2020 recession to those in the previous two recessions, this analysis constructs a time series of monthly employment that spans January 2000 to June 2020.

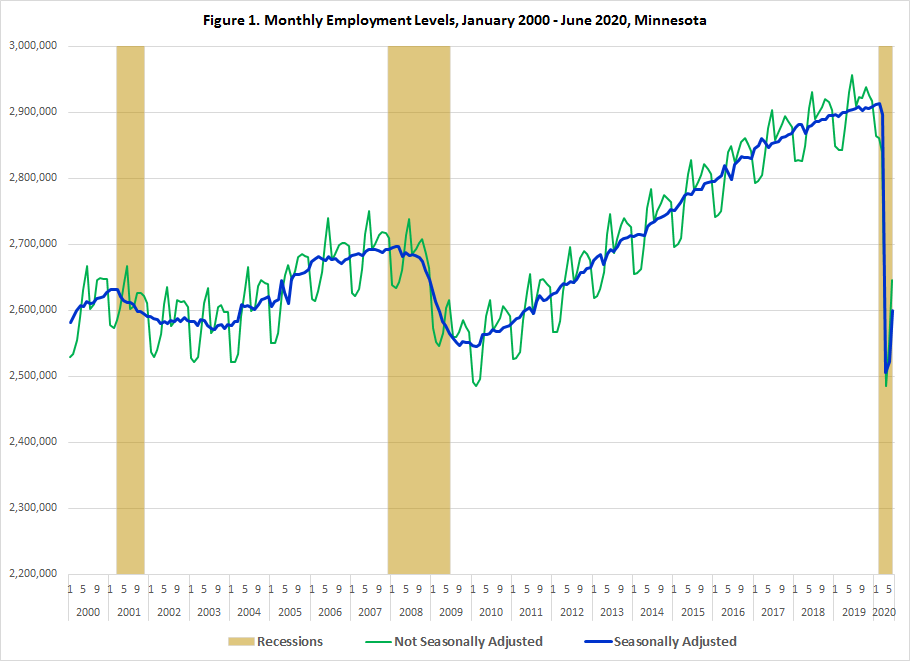

These series are then seasonally adjusted using the X-13-ARIMA (acronym for autoregressive integrated moving average) software developed by the Census Bureau. The goal of seasonally adjusting the time series is to identify and remove the regular patterns and to isolate the underlying trends in the employment series, specifically peaks and troughs. Figure 1 illustrates the seasonality in the Minnesota monthly employment series.

Figure 1 shows that the 2020 recession is very unusual. The magnitude of job losses in the 2001 recession and the Great Recession are dwarfed by the job losses in 2020. In fact, the 2020 recession has brought the monthly level of employment to its lowest level in the last 20 years in April of 2020. In addition, the employment contraction induced by COVID-19 occurred over an unbelievably short time of two months, compared to eight months in the 2001 recession and 18 months in the 2008 recession.

To measure the extent of job losses during a recession this analysis computes the difference between the peak employment and the trough employment within each recession. From February to April 2020, Minnesota businesses shed 406,692 jobs or 14% of peak employment in February. Comparatively, this is more than three times the contraction in employment that took place during the entire 18 months of the 2008 recession, and more than ten times the employment contraction of the 2001 recession. More precisely, Minnesota lost 127,319 jobs (or 4.7%) during the 2008 recession and only 35,615 jobs (or 1.4%) during the 2001 recession.

These significantly distinct employment contractions highlight the different character of normal recessions (2001 and the Great Recession) and the current pandemic recession. A normal recession is usually triggered by shocks to the financial markets, oil prices, or a set of industries which then spread throughout the whole economy. In addition, in a normal recession it takes time for reduced demand to become significant enough to compel employers to reduce their workforce. By contrast, the pandemic recession of 2020 was more diffuse and pervasive, touching all sectors of the economy and having a much faster impact than previous recessions. Social distancing and temporary business closures immediately reduced or dried up revenue sources for employers who in turn resorted to furloughs and layoffs to minimize business losses.

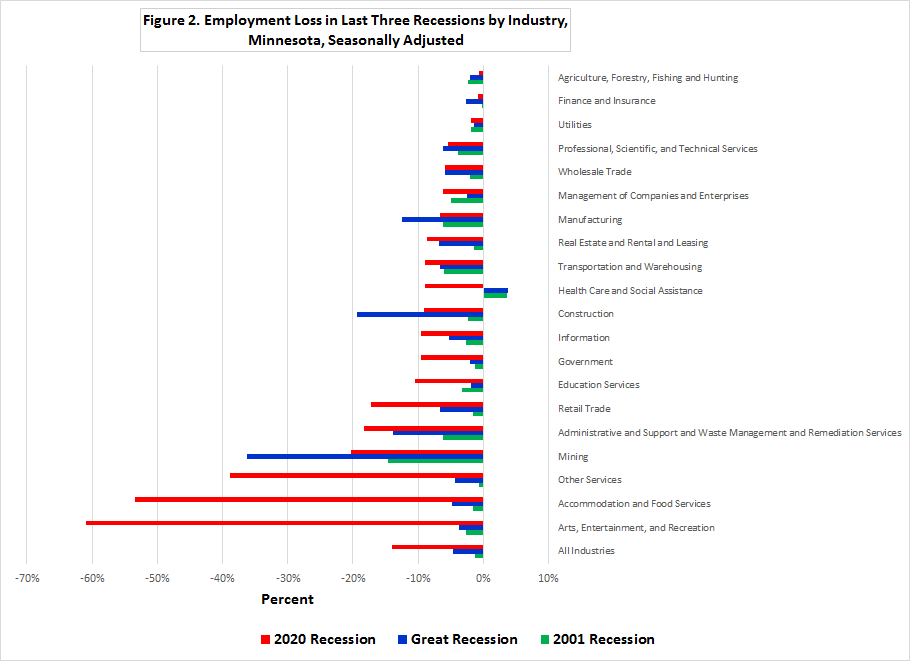

Extending the above time series analysis to each major industry shows that the impacts spread to all major industries (See Figure 2). Even the Health Care and Social Assistance industry, which escaped unscathed in the previous two recessions, was not spared from the COVID-19 havoc. Between February and April 2020, this industry saw its seasonally adjusted jobs shrink by 45,845 jobs or 9% of its peak employment in February. This surprising job contraction in the Health Care industry resulted from a combination of demand and supply shifts: the postponement of non-emergency procedures by both hospitals and consumers.

While job losses were pervasive, just a few industries bore the full brunt of the pandemic recession. About half of all job losses in the state were in only three industries: Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation; Accommodation and Food Services; and Other Services. COVID-19 caused these industries to shed jobs at unprecedented rates. The Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation industry suffered the deepest job contraction, dropping in April to about 61% of its February job level. As all spectator sports and other entertainment events were cancelled or postponed, seasonally adjusted employment declined from 54,244 in February to 21,161 in April, a loss of 33,083 jobs. This job contraction is about 18 times deeper than the level of job contraction experienced by this industry during the Great Recession when it lost only 1,852 jobs or 3.7% of its peak- level employment.

The second most heavily impacted industry by the pandemic recession is Accommodation and Food Services, which lost over half (or 53%) of its employment between February and April. At this rate and given the sheer employment size of this industry (it was the fifth largest employer in the state, on average), it translates to 125,735 jobs lost on a seasonally adjusted basis; by far the largest job contraction of any major industry. This staggering amount of job loss is 12 times the contraction suffered by this industry during the Great Recession. The distancing requirements, capacity limits, and travel restrictions have forced many employers in this industry to lay off most, or all, of their workers, and sometimes completely shut down.

The Other Services industry was also severely hurt by the COVID-19 disruptions, down close to 40% or 35,447 jobs between February and April. Like the two industries noted above, this level of job contraction shattered the levels experienced in the 2008 and 2001 recessions, which were 3,863 and 601 jobs, respectively.

Although far from the large losses of the above three industries, three additional industries suffered significant job contraction in the range of 20% to 17%. These industries include: Mining, Administrative and Support and Waste Management and Remediation Services, and Retail Trade. In absolute terms, the Retail Trade industry suffered a loss of seasonally adjusted 50,641 jobs, the second largest job loss overall.

All six of these hard hit industries have a common feature: most of their jobs cannot be performed remotely. Businesses and industries that don’t have the flexibility or the possibility to have their employees work from home were highly exposed to the onslaught of negative impacts of COVID-19. Some early economic research is pointing to the existence of a high correlation between the inability of workers to work remotely and the large declines in employment.1

The remaining industries suffered somewhat less extensive job contractions and can be divided into two groups. One group contains industries that lost between 10% and 5% of employment and the other group contains industries with job loss less than 2%. The latter group includes three industries: Utilities; Finance and Insurance; and Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting. All the remaining 11 industries belong to the former group.

Although COVID-19 caused all industries to shed jobs, not all industries suffered job losses that were worse than in the previous two recessions. In fact, Mining, Construction, Manufacturing, and Finance and Insurance all lost jobs at rates that were significantly less than those experienced during the Great Recession but still more than those of the 2001 recession. Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting is the only industry where COVID-19 resulted in job losses that were smaller than those of the previous two recessions.

So far, the analysis has focused on net job changes, or the difference between employment levels in the two months of peak and trough employment. This misses the employment dynamics that occur at the level of establishments during the contraction months. The labor market is inherently dynamic. Throughout the business cycle, some businesses expand, others contract, while others either open or close. Businesses that expand or open are responsible for job creation and businesses that contract or close are responsible for job destruction. This section describes how COVID-19 has affected the employment dynamics of Minnesota businesses.

To develop measures of monthly business employment dynamics, this analysis adopts the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) concepts of quarterly business employment dynamics to monthly employment levels.

Statistics of monthly business employment dynamics require developing a longitudinal database from establishment microdata. To build this database, the QCEW establishment data for first and second quarters of 2020 are linked. Then, monthly employment dynamics for a given month are computed by comparing the employment level in the given month to the employment level in the previous month. In each (call it “current”) month between February and June, five categories of establishments are created.

The four establishment types that experience employment changes between the current and previous months form the basis of the analysis of the monthly business employment dynamics. For comparison, this analysis computes the monthly business employment dynamics for the months of February to June in 2019 by linking the QCEW establishment data for first and second quarters of 2019.

All statistics discussed in the remainder of this article are derived from the monthly business employment dynamics and are not seasonally adjusted. To seasonally adjust the monthly business employment dynamics requires developing multitude longitudinal datasets and various monthly time series going back to January 2000, a task that is beyond the scope of this study. However, by comparing the same months between 2020 and 2019, most of the regular effects in each of the two years are accounted for, thus revealing mostly the COVID-19 effects.

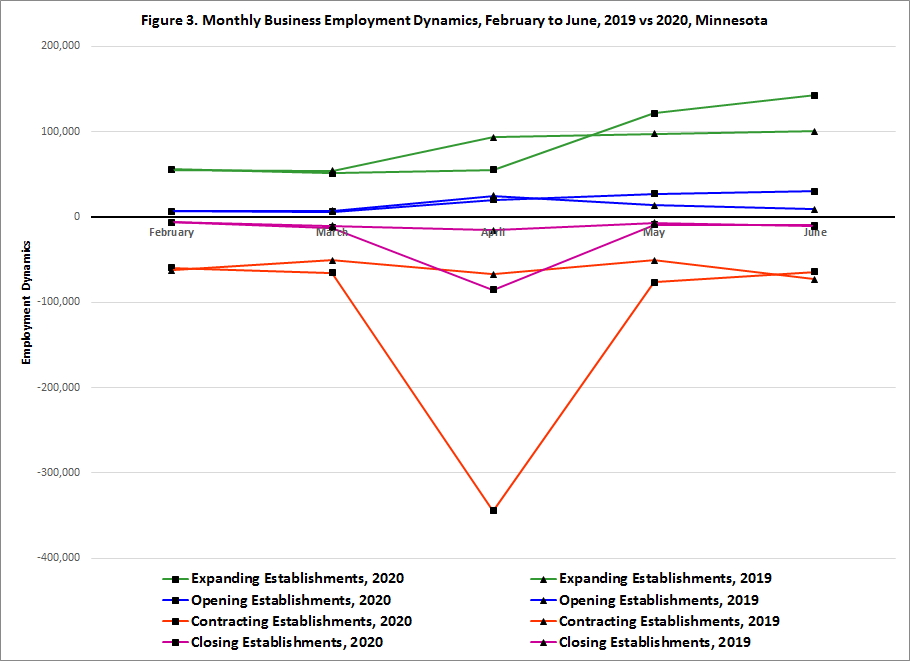

Figure 3 depicts how the monthly business employment dynamics between February and June 2020 compare to the same months in 2019. As expected, the monthly business employment dynamics for February were typical between the two years. In fact, except for contracting establishments, all types of establishments had numbers of jobs that were within 300 jobs between 2019 and 2020. However, starting in March the 2020 statistics of all four categories of establishments started to diverge from the 2019 trends. For example in each month during March and April, establishments that added jobs (expanding and opening) added fewer jobs in 2020 than in 2019 and establishments that cut jobs (contracting and closing) cut more jobs in 2020 than in 2019. These differences reached their maximums in April before reversing direction in May or June.

To capture the effects of the sudden changes to Minnesota businesses in March through April 2020, this analysis applies a statistical technique called the difference-in-differences. For each measure, call it X and which represents counts of jobs or establishments, of the monthly business employment dynamics, the following equation is applied:

COVID-19 effect on X = [(XMarch2020 – XFebruary2020) + (XApril2020 – XMarch2020)] - [(XMarch2019 – XFebruary2019) + (XApril2019 – XMarch2019)]

The equation can be rewritten as:

COVID-19 effect on X = [(XApril2020 – XFebruary2020)] - [(XApril2019 – XFebruary2019)]

This difference-in-differences gives the change in measure X, say jobs created at expanding establishments, that have occurred in March to April 2020 on top of what would be expected to occur normally as during March to April 2019. Thus, it captures the COVID-19 impact on measure X.

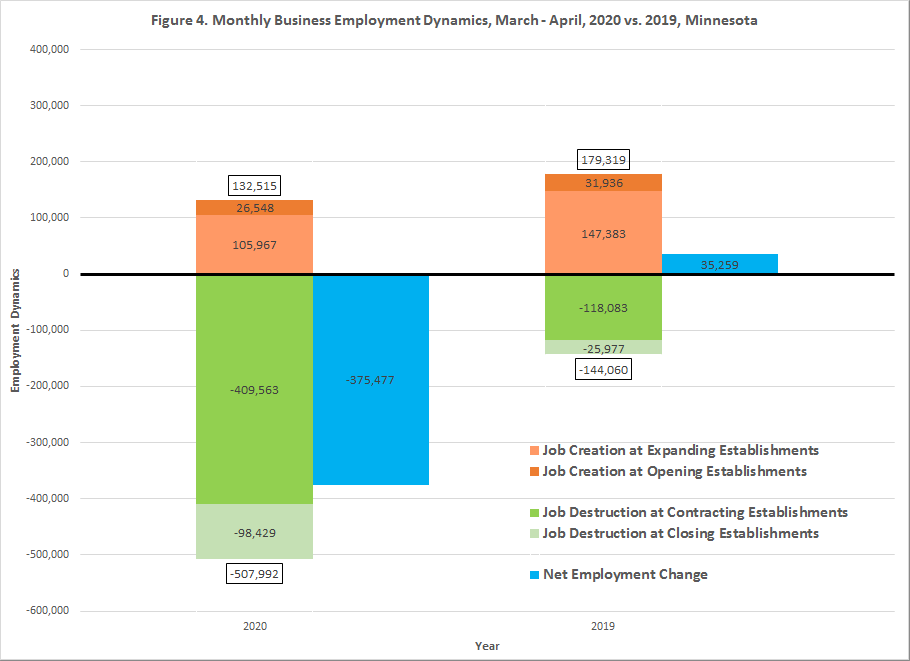

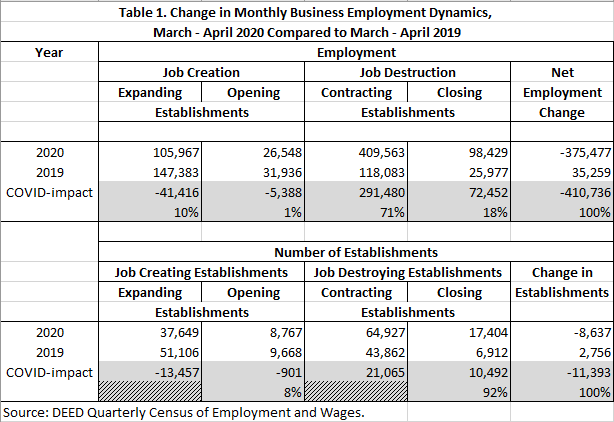

Figure 4 presents seven measures of the cumulative March to April monthly business employment dynamics for both 2019 and 2020. And Table 1 provides the COVID-19 impact on employment and number of establishments for the different categories of establishments.

A few additional relationships are worth mentioning here before discussing results in Figure 4 and Table 1:

Comparing each measure of the cumulative March-April monthly business employment dynamics between 2020 and 2019 unmasks how COVID-19 has impacted employment and the count of business establishments. To begin with, let’s look at the net employment change and work our way backwards to each component of the net employment change.

While Minnesota businesses added 35,259 jobs from March to April 2019, they lost 375,477 jobs during the same period in 2020. Thus, the COVID-19 impact on net employment change is 410,736 (obtained by applying our difference-in-differences: (-375,477) – (35,259)). This means that, COVID-19 has hit the state with two punches: first, it eliminated the overall ability of businesses to add 35,259 had they operated normally during from March to April, and second it wiped out 375,477 jobs from the economy.

This double-punch is also evident in the change in the number of establishments. In 2019, the state added 2,756 establishments as the number of opening establishments exceeded the number of closing establishments. However, in 2020, the state lost 8,637 establishments as the opposite occurred: more closing establishments than opening establishments. Thus, COVID-19 has caused the state a loss of 11,393 establishments (obtained by applying our difference-in-differences: (-8,637) – (2,756)).

The COVID-19 impact of 410,736 in net employment change can be decomposed into four COVID-19 impacts: (1) on job creation of expanding establishments, (2) on job creation of opening establishments, (3) on job destruction of contracting establishments, and (4) on job destruction of closing establishments. The sum of these four components equals the COVID-19 impact in net employment change.

The first component captures the COVID-19 impact on expanding establishments. About 10% of the COVID-19 impact on net employment change originated from reductions in job creation at expanding establishments. COVID-19 reduced the jobs created by expanding establishments by 41,416. Had COVID-19 never happened, Minnesota expanding establishments would have been expected to add 147,383 jobs from March to April. But, COVID-19 allowed only 105,967 jobs to be added from expanding establishments, a reduction of 28% in job creation capacity. In addition, fewer establishments expanded than normal. COVID-19 reduced the number of expanding establishments by 13,457, or 26% of the normal size of this group of establishments compared to 2019 (See Table 1).

Second, COVID-19 also reduced the job creation process of opening establishments. Opening establishments only added 26,548 jobs from March to April 2020 compared to 31,936 jobs from March to April 2019. That’s a drop of 5,388 jobs, or a reduction of 17% in job creation capacity of opening establishments because of COVID-19. In addition, there were 901 less opening establishments in 2020 than in 2019. This means that COVID-19 not only hurt the numbers of job creation and number of opening establishments, but also the rate of job creation at opening establishments. In fact, an opening establishment in March-April 2020 added on average 3 jobs compared to 3.3 jobs in 2019.

Third, the largest COVID-19 impact, in absolute terms, was inflicted on contracting establishments. These establishments terminated 409,563 jobs from March to April 2020, of which 291,480 (or 71%) can be blamed on COVID-19. Put differently, COVID-19 caused the number of jobs destroyed by contracting establishments to increase by a factor of about 2.5 over the normal level of 2019. This high level of job destruction is the result of two factors acting together: an increase in the number of contracting establishments and an increase in the average job reduction at each contracting establishment. COVID-19 caused 21,065 more establishments than normal to reduce their employment levels. Moreover, while an average contracting establishment in 2019 shrank by 2.7 jobs, that rate jumped to 6.3 jobs in 2020.

Finally, the closing establishments eliminated 72,452 jobs as a result of COVID-19. This is 3.8 times the number of jobs terminated at closing establishments in 2019, making job destruction at closing establishments the hardest hit, in relative terms, by COVID-19. In fact, there were 10,492 establishments that closed from March to April 2020, that is over and above the normal closings for all of 2019. In addition, COVID-19 caused the rate of job termination to increase significantly. On average, about 3.8 jobs were terminated by a closing establishment from March to April 2019, but in 2020 that rate jumped to 5.7 jobs.

These results suggest that the COVID-19 impact on count of jobs and businesses has been significant and pervasive. It affected all four types of establishments. On one hand, the job creating establishments have seen their ability to contribute to job growth reduced through reduction in their counts and rate of jobs created per establishment. On the other hand, the job destroying establishments have been pushed to higher levels of job destruction through increases in their numbers and rate of job destruction per establishment. These joint and opposing effects render the net employment change much larger than it would have been in a non-pandemic world.

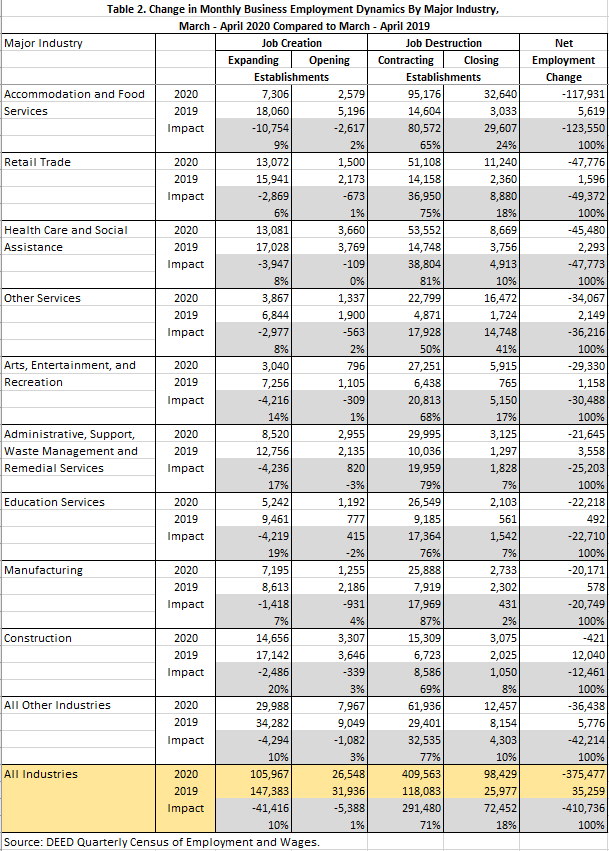

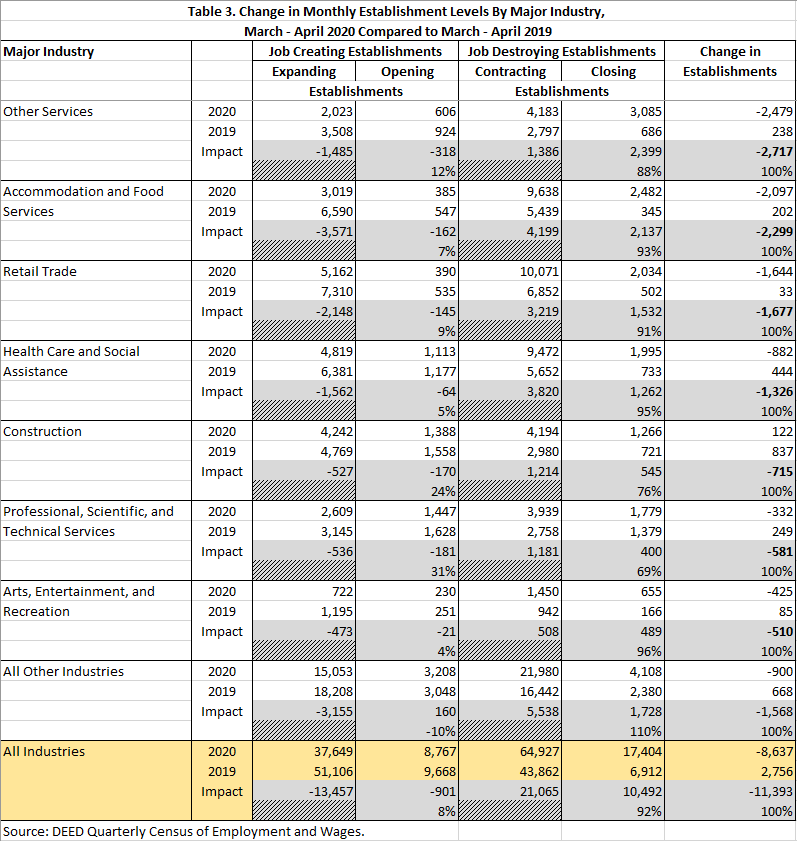

Table 2 presents the monthly employment business dynamics for the March to April period in 2019 and 2020 and the COVID-19 impacts on the count of jobs for industries most impacted by COVID-19 and Table 3 presents similar measures on the count of establishments. The industries listed in Tables 2 and 3 are ranked in descending order by the size of COVID-19 impact on net employment change and establishment change, respectively. Except for a few instances, the pattern of how COVID-19 impacted the counts of jobs and establishments at the state level is also evident in each major industry.

In terms of count of jobs, the Accommodation and Food Services industry endured the largest COVID-19 impact to all four establishment types (See Table 2). In March-April 2020, COVID-19 inflicted a loss of 10,754 jobs in possible new jobs added by expanding establishments, a loss of 2,617 jobs in possible new jobs added by opening establishments, a removal of 80,572 jobs from contracting establishments, and removal of 29,607 jobs from closing establishments. All this adds up to a whopping loss of 123,550 jobs as captured in the net employment change. Viewed differently from the perspective of just net employment change, it is composed of the loss of would-be job growth of 5,619 jobs that would have occurred under normal conditions and the elimination of 117,931 jobs in March-April 2020.

The COVID-19 impact of 123,550 jobs lost in the Accommodation and Food Services industry amounts to 30% of the overall COVID-19 impact on jobs. No other industry is even close to this level of impact across all four types of establishments. Moreover, no other industry ranks as high in terms of COVID-19 impact in all five measures of business employment dynamics.

This implies that there is significant heterogeneity in the way COVID-19 has affected industries. For instance, different industries sustained the second and third largest COVID-19 impacts according to the business employment dynamics measure being considered. The second and third worst COVID-19 impacts to:

Table 3 reveals that the heterogeneity in COVID-19 impact across industries is also present in the number of establishments. Several results are noteworthy. First, the largest COVID-19 impact to the change in establishments was in the Other Services industry with a reduction of 2,717 businesses, of which 238 businesses should have been added had March-April 2020 resembled March-April 2019 and 2,479 establishments lost in March-April 2020. Second, the next three largest change in impacts in number of establishments were in Accommodation and Food Services, Retail Trade, and Health Care and Social Assistance. Third, the ordering of these four industries was the same as for the COVID-19 impact on the number of closed establishments. Collectively, these four industries accounted for 70% of the total numbers of change in establishments and of closing establishments.

Fourth, Accommodation and Food Services suffered the largest COVID-19 impact to both its number of expanding and contracting establishments. COVID-19 reduced the number of expanding establishments in this industry by 3,571 businesses. Only 3,019 businesses added jobs in March-April 2020 compared to 6,590 businesses that expanded in March-April 2019. To make matters worse, the number of contracting establishments almost doubled. The number of contracting establishments jumped from 5,439 businesses in March-April 2019 to 9,638 businesses in March-April 2020. Thus, in Accommodation and Food Services, 4,199 contracting businesses were the result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lastly, except for Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services, all seven industries listed in Table 3 have experienced large jumps in the number of closing establishments due to COVID-19. For example, in Accommodation and Food Services the number of closing establishments jumped from 345 businesses in March-April 2019 to 2,482 businesses in March-April 2020, which represents an over six-fold increase. Similarly, in Other Services and Retail Trade the number of closing establishments jumped between March-April 2019 and March-April 2020 from 686 to 3,085 businesses and from 502 to 2,034 businesses, respectively.

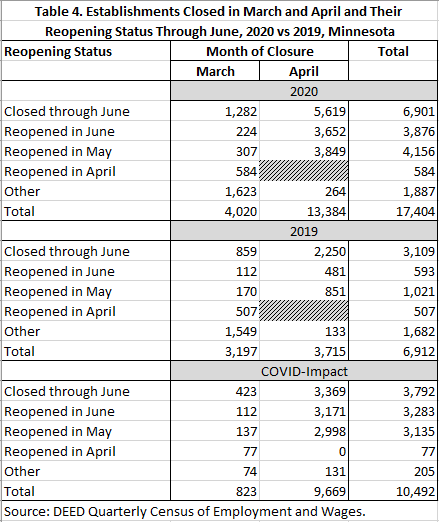

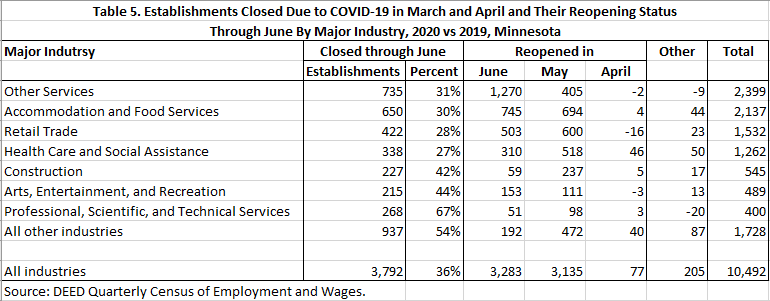

Table 4 presents the reopening status of closing establishments at the state level and Table 5 presents similar statistics for the major industries discussed above. A closed establishment is defined as reopened if it shows non-zero employment following its month of closure. And a closed establishment is defined as still closed as of June if it continues to show zero employment through the month of June (the last month of available employment data). To assess the reopening status of closed establishments in March-April, this study groups them into those that were still closed as of June of the same year, those that reopened in June, and those that reopened in May or April and kept non-zero employment through June. Finally, the study isolates the COVID-19 impact on the reopening status of closed establishments by applying the difference-in-difference statistical method discussed above.

Table 4 shows that out of the 10,492 business closures attributed to the pandemic, 6,495 (or 62%) businesses reopened and were back in business as of June. Half of these establishments reopened in May and the other half reopened in June. However, 3,792 (or 36%) businesses were still closed in June. Out of this group, 3,369 (or 89%) businesses were closed for the months of May and June and 423 (or 11%) are still closed since March.

Table 5 breaks down the reopening status of the closing establishments by major industry (or the difference-in-differences estimates).In all four industries with business closures greater than 1,000 establishments, 70% were back operating by June. Moreover, as of June, 30% of the closing establishments in these industries were still closed. Between these industries, they accounted for 57% (or 2,145 out of 3,792) of all businesses that didn’t reopen by June. Although the remaining three industries in Table 5 have small numbers of closing establishments, they had significantly different rates of reopening. For example, the Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services, which had 400 COVID-caused closing establishments, 67% of those businesses were still closed in June.

That said, it is important to recognize that we cannot make any inferences about whether the businesses that were still closed in June are permanently closed. To make such determinations requires establishment data from the QCEW for at least the third and fourth quarters of 2020 which will not be available until mid-2021.

Among the businesses that reopened, there is considerable heterogeneity across industries in the duration of closure. In Other Services, 24% of the closing businesses reopened in May while 76% reopened in June. By contrast, 63% of the closing businesses in Health Care and Social Assistance reopened in May and 27% reopened in June.

These results further suggest that the COVID-19 disruptions did not affect all industries and businesses equally. Some businesses could continue operation by offering their employees remote work or by being deemed essential, while others couldn’t because they were required to close or couldn’t afford to do business remotely. In addition, industries that depend on face-to-face business interactions were susceptible to the sudden loss of revenue and the accumulating costs brought about by COVID-19.

Finally, some figures in Table 5 provide negative numbers. It is not an anomaly; they simply indicate that for that category the difference-in-differences is negative, meaning that the figures for 2019 were greater than those for 2020.

This study has focused mainly on the initial COVID-19 impact on Minnesota businesses. It used business census data from the QCEW to develop monthly business employment dynamics. The results confirm that COVID-19 has caused the state tremendous job losses and business closures not seen in the previous two recessions of 2008 and 2001. Between February and April 2020, the state lost 14% of its jobs, compared to 5% over 18 months during the Great recession.

The results suggest that COVID-19 has hit the labor market with a double punch. First, it hit expanding and opening establishments by reducing their capacity to add jobs. Second, it delivered its strongest punch to the contracting and closing establishments by increasing their job destruction. The results also highlight the significant heterogeneity in COVID-19 impacts on industries and their engines of job creation and job destruction. Four industries suffered the most in job contraction and business closures: Accommodation and Food Services, Retail Trade, Health Care and Social Assistance, and Other Services. Finally, the results indicate that COVID-19 caused the closing of 10,492 businesses, of which 3,792 business, or 36% of closures, were still closed in June.

1Verecky, Betsy. Telecommuting Exposes Fault Lines in COVID-19 Economy. MIT Sloan School of Management.