by Dave Senf

March 2023

While private sector employment has come charging back, the public sector is lagging. Current Employment Statistics (CES) data show that recovery of public sector employment in Minnesota and nationally has fallen behind private sector employment over the last two years. Most of the sluggish rebound has been in local governments including public schools.

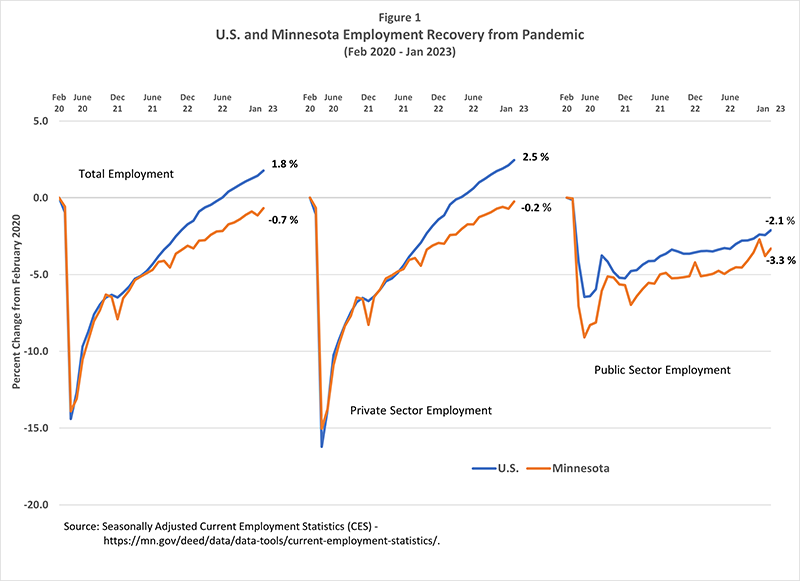

Both private and public employment plunged in April and May 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic first hit the U.S. economy. In the immediate aftermath, private and public employment dropped 15% and 9.1% respectively in Minnesota from February's level before bottoming out in April and May (see Figure 1). However, Minnesota's decline in government jobs was steeper than nationally, and the state's recovery of government jobs has lagged the government job recovery across the U.S. over the last two years.

Elevated early retirement from government payrolls, rapidly increasing wages in the private sector compared to relatively static public sector wages, declining public school enrollment numbers, acute labor shortages in certain occupations (such as nursing, policing, corrections, and teaching) and less nimble hiring processes than in the private sector have been flagged as contributors to the lagging government job recovery.

Private sector employment accounted for roughly 86% of Minnesota's 2022 annual average total employment of just over 2.9 million jobs. In fact, the private sector is just 6,200 jobs, or 0.2%, short of its pre-pandemic level in February 2020 as of January 2023 . Minnesota's public employment as of January 2023 was 14,100 jobs, or 3.3%, short of its pre-pandemic level, with most of the deficit in local government.

The 14% of total employment in the state accounted for by government jobs (409,000 jobs) was spread across 31,800 federal government jobs (1.1% of total employment), 57,600 state government jobs in higher education (2%), 40,300 state government jobs outside of higher education (1.4%), 138,000 local government education jobs (4.7%) and 141,000 local government jobs outside of excluding education (4.8%).1

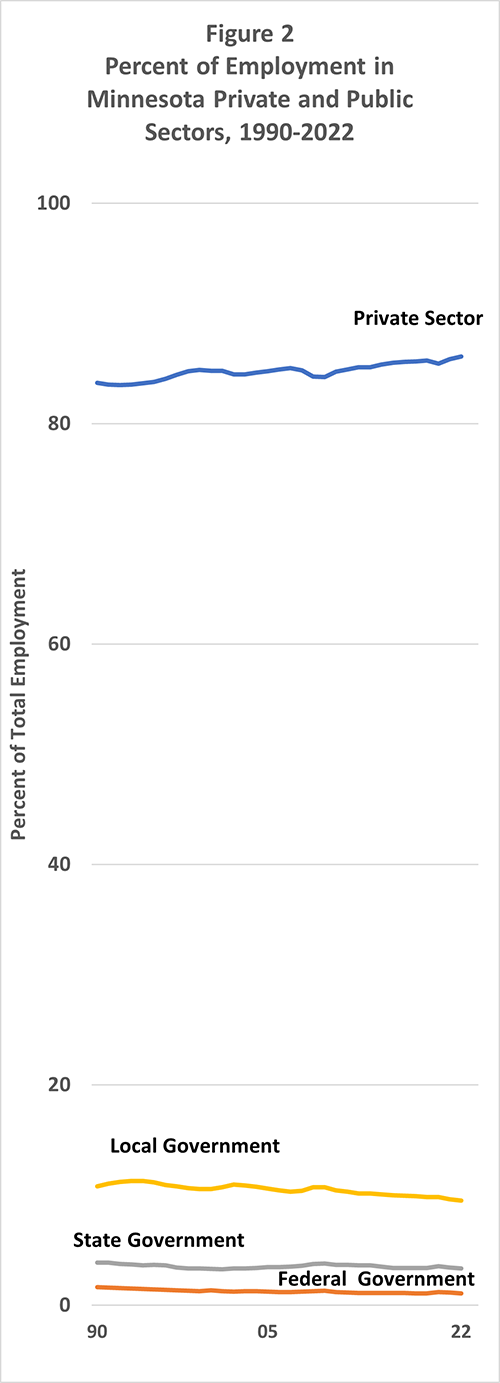

Figure 2 provides a historical perspective of public employment in Minnesota over the last four decades. The percent of all employment on private payrolls has been gradually increasing over the last 40 years, reaching 86.0% in 2022, up from 83.7% in 1990. The years that show a drop in the percent of private sector jobs correspond with recession years. Private sector job losses during recessions are deeper than public sector job declines, as was the case in 2020.

Figure 2 provides a historical perspective of public employment in Minnesota over the last four decades. The percent of all employment on private payrolls has been gradually increasing over the last 40 years, reaching 86.0% in 2022, up from 83.7% in 1990. The years that show a drop in the percent of private sector jobs correspond with recession years. Private sector job losses during recessions are deeper than public sector job declines, as was the case in 2020.

All three levels of government jobs (federal, state, and local government) have grown slower than private jobs over the last 40 years and have seen their percent of total employment inch downward. Local government jobs have seen the biggest percent drop, followed by federal government and state government jobs. Some of the shifting percentages have been due to the transfer of public sector jobs to non-profit jobs (which are then included in private employment). For example, hospital employment that used to be counted as local government jobs at institutions such as Regions Hospital (formerly Saint-Paul Ramsey County Medical Center) and Hennepin Healthcare (formerly Hennepin County Medical Center) are now classified as private sector employment.

In 2021, Minnesota ranked ninth lowest in the U.S. in percent of employment accounted for by public employment. Minnesota was third lowest in federal government percent and 16th lowest in state and local government percent (2022 data hasn't been released for all states yet).

Compared to other states, Minnesota currently has the fifth steepest percent decline in public sector employment compared to the pre-pandemic level (February 2020 compared to December 2022) using CES employment data.3 Minnesota's public employment shortfall is topped by larger shortfalls in New Hampshire, Louisiana, West Virginia and Ohio. Only five states (Alabama, North Dakota, Utah, Maryland and Idaho) have completely recovered all public sector jobs lost over the pandemic.

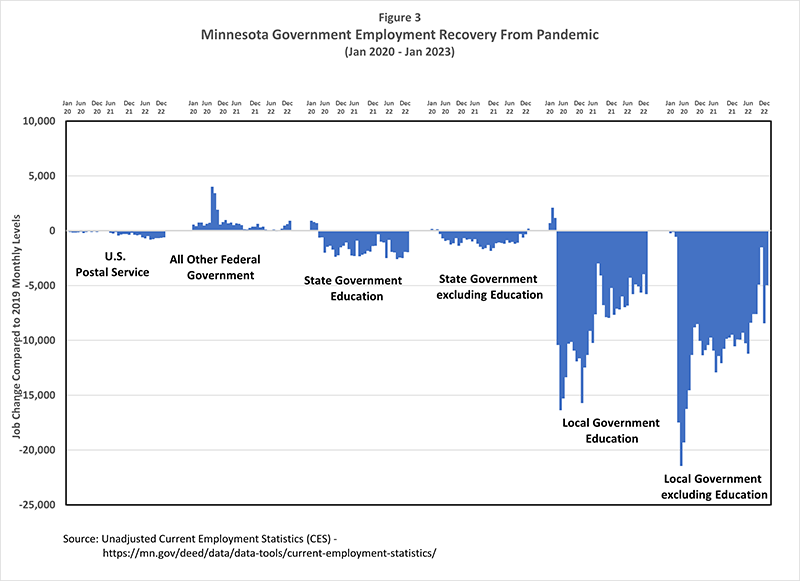

Unadjusted CES employment estimates are used in Figure 3 to breakdown Minnesota's lagging public employment in greater detail over the pandemic. When using unadjusted employment data, the only valid comparison is comparing the same month from year to year, making an over-the-year comparison. In Figure 3, employment levels for each month from January 2020 to January 2023 are compared to corresponding 2019 months.

Government job loss during the pandemic has been concentrated in local government. During the first year of the pandemic local education jobs were slightly lower in local government units outside of education. Currently job loss is slightly lower at county, city, township offices than at local public schools. The deepest cuts were early in 2020 in local government jobs outside of education. Native American casino-related employment is included in non-education local government employment so the large drop from April to June 2022 in non-education local government employment was partially related to the shuttering of casinos during the early months of the pandemic.

U.S. Postal Service jobs, which hardly changed during 2020, have resumed a long-term gradual decline and are roughly 600 jobs below 2019 levels. Federal government employment outside of Postal Service jobs have inched above pre-pandemic levels during the last few months of 2022 and are now roughly 900 jobs above 2019 levels.

State government education jobs continued to decline in 2022 as Minnesota's public higher education institutions adjust to shrinking student enrollment. Enrollment numbers are falling as the college age population declines and a very tight labor market boosts the chances of landing a job without needing college credentials. State government education employment at the end of 2022 is roughly 2,000 jobs below 2019 levels. State government employment outside of education has recovered all its pandemic period decline and currently 200 jobs above pre-pandemic level.

More notably, local government education employment (at public elementary and secondary schools) remains 6,000 jobs (4%) below pre-pandemic levels. Declining enrollment at public schools due to students moving to private and charter schools, the falling overall school age population, and a shortage of qualified applicants for job vacancies have combined to slow the recovery of local government education staffing.

Local government employment outside of education was roughly 5,000 jobs (3.4%) short of its pre-pandemic level at the end of 2022. This employment gap in counties, cities and townships covers a wide variety of services. For example, Hospitals; Executive, Legislative, & Other General Government Support; Accommodation and Amusement, Gambling & Recreation; Nursing & Residential Care Facilities; Transportation & Ground Passenger Transportation; and Justice, Public Order & Safety Activities are where most of the employment shortfalls exist.

Table 1 lists the top 20 occupations in state and local government outside of education and hospitals. Only a few jobs listed in the table are employed predominately in the public sector. The other common jobs in the public sector are also common jobs in the private sector, meaning that public employers are competing with private employers when hiring for open positions, which can make hiring more difficult.

| Top State and Local Government Occupations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top Occupations of State Government Employment Excluding Education and Hospitals | Top Occupations of Local Government Employment Excluding Education and Hospitals | |||

| Code | Occupational Title | Code | Occupational Title | |

| 13-1198 | Project Management Specialists and Business Operations Specialists, All Other | 33-3051 | Police and Sheriff's Patrol Officers | |

| 43-4031 | Court, Municipal, and License Clerks | 33-2011 | Firefighters | |

| 33-3012 | Correctional Officers and Jailers | 21-1021 | Child, Family, and School Social Workers | |

| 47-4051 | Highway Maintenance Workers | 43-4031 | Court, Municipal, and License Clerks | |

| 13-2081 | Tax Examiners and Collectors, and Revenue Agents | 49-9071 | Maintenance and Repair Workers, General | |

| 31-1120 | Home Health and Personal Care Aides | 43-9061 | Office Clerks, General | |

| 13-1041 | Compliance Officers | 43-4061 | Eligibility Interviewers, Government Programs | |

| 15-1241 | Computer Network Architects | 47-4051 | Highway Maintenance Workers | |

| 23-1011 | Lawyers | 33-3012 | Correctional Officers and Jailers | |

| 13-1111 | Management Analysts | 53-1047 | First Line Supervisors of Transportation & Material Moving Workers | |

| 17-3022 | Civil Engineering Technicians | 53-3052 | Bus Drivers, Transit and Intercity | |

| 19-2041 | Environmental Scientists and Specialists, Including Health | 51-8031 | Water and Wastewater Treatment Plant and System Operators | |

| 15-1256 | Software Developers and Software Quality Assurance Analysts and Testers | 21-1092 | Probation Officers and Correctional Treatment Specialists | |

| 15-1211 | Computer Systems Analysts | 33-1012 | First-Line Supervisors of Police and Detectives | |

| 21-1015 | Rehabilitation Counselors | 29-1141 | Registered Nurses | |

| 17-2051 | Civil Engineers | 21-1093 | Social and Human Service Assistants | |

| 23-1023 | Judges, Magistrate Judges, and Magistrates | 37-2011 | Janitors and Cleaners, Except Maids and Housekeeping Cleaners | |

| 33-3051 | Police and Sheriff's Patrol Officers | 43-3031 | Bookkeeping, Accounting, and Auditing Clerks | |

| 13-2011 | Accountants and Auditors | 39-9032 | Recreation Workers | |

| 49-9071 | Maintenance and Repair Workers, General | 37-3011 | Landscaping and Groundskeeping Workers | |

| Source: Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development, Occupational Staffing Patterns by Industries. | ||||

The rebound in Minnesota's public employment since the pandemic recession continues to lag the recovery in private employment.

Some of the public and private employment gap is due to pandemic-related causes like lower school enrollment and a decline in mass transit ridership, both of which may take years to reverse. Another strike against government employment is that the public sector workforce is slightly older than the private sector workforce, so retirement rates in the public sector would have likely exceeded private sector retirement rates. This loss of older workers provides another hurdle in getting public employment back to pre-pandemic levels.

Public sector employers, just like private employers, are now hiring in a very tight labor market where the number of workers responding to job openings are significantly below levels seen in the past. In order to compete with their private sector counterparts, government agencies will likely need to raise wages and benefits in this very competitive labor market, which will likely remain tight in the coming year.

1Based on 2022 annual average of unadjusted Current Employment Statistic (CES) employment data.

2There are two main sources of employment estimates for Minnesota, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) and Current Employment Statistics (CES). The article "Variations in Employment in the CES and QCEW Programs" in Minnesota Trends September 2018 provides key explanations of how the estimates differ.