Are Skilled Workers Scarce?

by Alessia Leibert

June 2013

The skills gap debate and its pitfalls

A skills gap is the difference between the skill levels of the available workforce and the skills necessary to meet job requirements. Skills gaps have often been used as a simple narrative to explain the contradiction between the current high level of unemployment in the United States and the alleged inability of employers to fill open positions. This over-simplified narrative, however, has suffered from two main flawed assumptions:

- It assumes skills gaps are synonymous with hiring difficulties. Hiring difficulties often manifest themselves as a lack of qualified candidates who apply for a job. This can create the impression of a widespread lack of occupational workforce skills and, perhaps, of educational credentials. But, aside from lacking skills, there could be many other reasons why qualified candidates do not apply for a job or are not considered to be a good match for the job. For instance, mismatches can result from recruiting strategies that do not properly identify the desired skill set, unattractive job characteristics that discourage qualified candidates from applying, or an over-qualified candidate pool as opposed to an under-qualified candidate pool.

- It assumes that skills mismatches prevent employers from hiring, which in turn is assumed to hurt firm competitiveness. However, skills-related hiring difficulties are not necessarily barriers that prevent hiring for a particular position. Additionally, sometimes firms set stringent qualification requirements because they are not in a hurry to hire.

To investigate the existence and causes of hiring difficulties in Minnesota and determine how many are specifically attributable to skills gaps relative to other factors, the Minnesota Labor Market Information Office rolled out a Hiring Difficulties Survey based on its existing semi-annual Job Vacancy Survey.

Quick Facts: Hiring Difficulties Survey

|

The extent of hiring difficulties in Minnesota

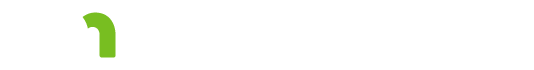

Figure 1 displays the main survey findings. Less than a half (43 percent) of all vacancies reported in spring and fall of 2012 were hard-to-fill. Hiring difficulties varied widely by occupation, with Nursing having the lowest incidence (32 percent) and Production having the highest incidence (68 percent).

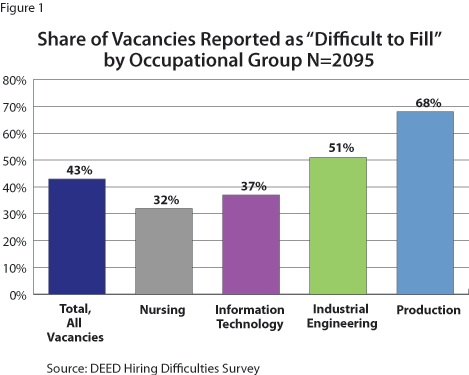

When vacancies are broken down by industry (Figure 2), the same high concentration — above 50 percent — of hiring difficulties exist in the Manufacturing sector as in Industrial Engineering and Production, occupations almost exclusively found in Manufacturing industries. Both results point to Manufacturing as the segment of Minnesota’s economy where employers are struggling the most to fill available openings.

Hiring difficulties also varied by region. Fifty two percent of vacancies in Greater Minnesota were hard to fill compared to the Twin Cities Metro Area with 36 percent.

These overall findings about the magnitude and distribution of hiring difficulties serve as a background to the next section of the article that takes a closer look at the nature and potential causes of hiring difficulties and, specifically, at the incidence of skills gaps.

Measuring the skills gap: Employers’ perspectives about potential causes of hiring difficulties

In order to identify hiring difficulties, employers were first asked “Did you have — or are you having — difficulties filling the position?” Next, they were given an opportunity to share their perspectives about why some positions are hard to fill, choosing from two main areas: supply-side factors or demand-side factors.

- Supply-Side Factors: Hiring difficulties caused by a mismatch between job requirements and the training, skills, and experience of applicants (true skills mismatches).

- Demand-Side Factors: Hiring difficulties caused by problems that are unrelated to candidates’ qualifications, such as unattractive work hours, inadequate compensation, geographic location of position, poor image of the firm or industry sector, or ineffective recruiting, and so forth.

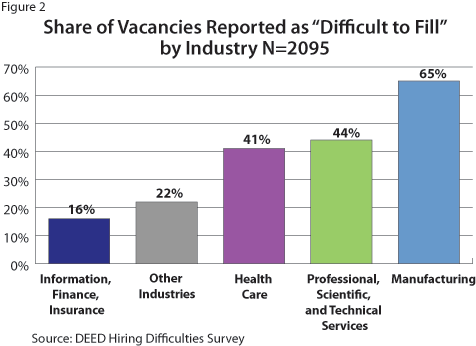

While employers reported general hiring difficulties in 43 percent of vacancies, only 15 percent of all vacancies were hard-to-fill exclusively because of skills mismatches (Figure 3).

Far more common were hiring difficulties where employers also identified a demand-side problem in conjunction with a supply-side problem. This indicates that skills mismatches rarely occur in isolation from demand-side factors. Least common were hiring difficulties that were attributed exclusively to factors unrelated to the supply of skills.

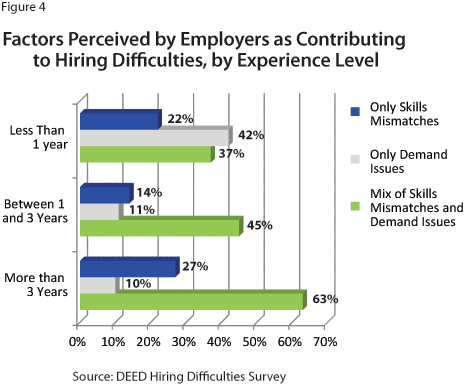

When responses are broken down by experience level as shown in Figure 4, we notice a high concentration (42 percent) of purely demand-driven hiring difficulties in vacancies requiring less than one year of experience, corresponding to the entry-level job market. When asked to identify the reasons for hiring difficulties in this group of vacancies, employers attributed 40 percent fully or in part to unattractive wages/compensation.

Interestingly, pure skills mismatches were not concentrated in high-experience vacancies as one would have expected, but rather in vacancies requiring intermediate work experience, from one to three years. The difficulties in filling high-experience positions were overwhelmingly caused by a mix of supply and demand issues. A closer look at these cases reveals that 87 percent were caused by the inability to find candidates with specialized skills, yet one-half of these also mentioned location as a contributing factor. This result is a clear demonstration of how supply problems can interact with other issues like geographic mismatches. Some employers feel that attracting experienced workers would be much easier if the firm were located in a different area. An additional and unexpected finding was that Greater Minnesota regions experienced geographic mismatches at rates not much higher than the Metro Area. Some of the locations indicated as “problematic for hiring” were actually in the Twin Cities Metro Area.

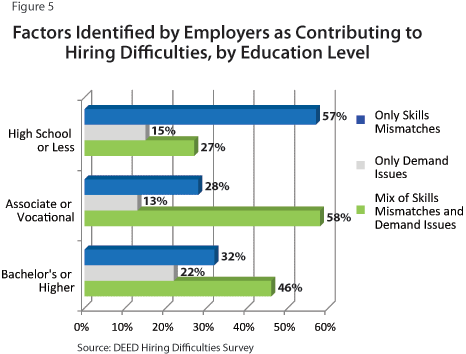

Some surprising results also emerge in the distribution of skills mismatches by education level (Figure 5). In fact, employers were more likely to report skills mismatches as the exclusive reason for hiring difficulties for jobs requiring no post-secondary education (57 percent). On the other end of the spectrum, for positions requiring a bachelor’s degree or higher, pure skills mismatches were cited in just 32 percent of the cases, and demand-side reasons in 22 percent of cases. The implication is that, in general, education level alone is not driving skills mismatches.

Thus, skills mismatches were sometimes found to be related to inadequate levels of experience, but not to inadequate levels of education. This demonstrates that skills mismatches, as a cause of hiring difficulty, cannot automatically be assumed to be the result of a shortage of skilled workers.

The incidence and characteristics of skills mismatches by occupation

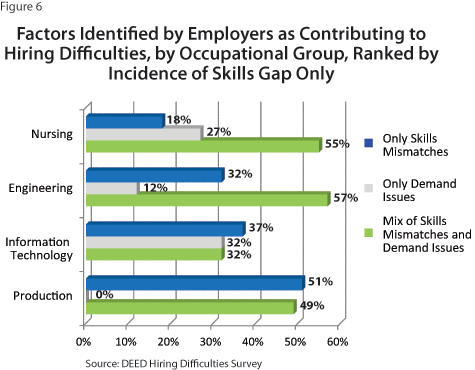

When responses are broken down by occupational group (Figure 6), three scenarios emerge:

- Occupations with a low incidence of pure skills mismatches relative to other reasons for hiring difficulties (nursing, with 18 percent);

- Occupations with a moderate incidence of pure skills mismatches (engineering, 32 percent, and IT, 37 percent);

- Occupations with a high incidence of pure skill mismatches (production, 51 percent).

It is important to recall that these occupations were intentionally selected precisely because of anecdotal evidence of skills-related hiring difficulties. Therefore, there was a high probability of finding skills gaps in these fields.

Following are the summarized results by occupational group.

NURSING: Low incidence of skills-related hiring difficulties

Among all occupational groups surveyed, Nursing had the lowest incidence of hiring difficulties at 32 percent (Figure 1). Of that minority only a small subset (18 percent) were perceived by employers as related exclusively to skills mismatches, while 27 percent were exclusively caused by demand factors, and the remaining 55 percent were driven by a combination of supply and demand factors (Figure 6).

When skills mismatches were cited as a problem, the challenge for employers was finding candidates with experience in a specific role or industry as opposed to more formal education. The following quotations illustrate this important finding:

- “Candidates had the years of experience as an RN, but their experience was in long-term care facilities not in a hospital, and that’s a different animal.”

- “We sometimes get nurses who work in the home and are not required to do case-management, and thus lack the skills we need to do prompt and efficient paperwork.”

When demand-side factors were cited as the main challenge, undesirable location was most frequently mentioned, followed by substandard wages or compensation, undesirable work shifts, and competition from other employers to attract the most experienced candidates. Here are a few quotations:

- “From this area people can easily commute to the Metro area or to Rochester where there are a lot of other job opportunities.”

- “Our industry has a much lower wage base than others. So, perhaps the reason we can’t get enough applicants is that everybody knows the pay is $10 a day lower.”

- “We can’t compete with places that offer high hiring bonuses.”

- “The position has 10-hour shifts which are tougher to fill.”

Overall, advanced specialty nursing vacancies — which included Nurse Practitioners and Nurse Anesthetists — were much harder to fill than Registered Nurses vacancies. This obvious lack of evidence of a shortage of RNs might be the effect of years of effort by the Healthcare Industry to alert career seekers and educators to potential future shortages as well as a very successful effort on the part of post-secondary institutions in Minnesota to align the supply of nursing graduates with the anticipated industry demand.

INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING: Moderate incidence of skills-related hiring difficulties

As illustrated in Figure 1, one out of two industrial engineering vacancies were reported as hard to fill. One out of three hard-to-fill positions was perceived as driven by skills mismatches with no other demand-side factors identified. The overwhelming reason for hiring difficulties, accounting for 57 percent of cases, appears to be a blend of supply and demand factors (Figure 6).

Employers’ comments reveal that finding new graduates in engineering was not a problem for employers. Rather, applicants lacked hyper-specialized experience or a unique blend of skills that could be extremely difficult to find even when plenty of people apply. The following quotations illustrate this point:

- “Hiring entry-level manufacturing engineers is pretty easy, but finding experienced workers is more challenging.”

- “There were enough applicants with the right training, but they did not have the right experience after getting their degree. We were looking for someone with a similar experience with another manufacturer.”

- “We were looking for experience in Atomic Force Microscopy.”

- “We always have difficulties filling this position because we require specific experience in test engineering in the electronics industry. There might be total of 150 qualified people in the Midwest! Training these people internally is a big investment for a company, that’s why there are so few qualified candidates.”

The difficulty in Engineering seems primarily one of matching the experience requirements of a vacancy with the experience profile of those who apply. Unfortunately, this match is hard to achieve even through additional years of training or experience if that additional training is not specifically tailored around the needs of a particular industry or even an individual employer. That’s probably why some employers prefer to hire engineering candidates with work-based experience such as internships.

Other recruiting difficulties stemmed from substandard wages, undesirable geographic locations, or lack of candidates interested in the type of work.1

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY: Moderate incidence of skills-related hiring difficulties

As illustrated in Figure 1, hiring difficulties impacted only 37 percent of vacancies in IT occupations. Of that minority, the reasons for the difficulties were fairly evenly split between those exclusively from skills deficiencies (37 percent), those exclusively from unattractive demand or other factors (32 percent), and those from a mix of skills deficiencies and unattractive demand (31 percent).

In IT as in engineering, the main supply-side problem was work experience and — importantly — the skills obtained through that experience.

- “The applicant pool with IT positions is often very small because people tend to have more of a general skill set compared to the specialized skill set that we need.”

- “It is hard to find people with Mainframe skills (older skills like COBOL that are no longer taught). Also, many people with skills aren’t interested in working with older technologies.”

- “Low unemployment in the IT field creates a lot of competition, therefore — despite the huge response to the ads — we are not getting the right type of candidate. We are either getting candidates with too much experience (overqualified) or zero experience.”

- “We’re looking for someone with specific technical skills and experience in Window Installer, Install, Shield, Visual Studio, and familiarity with image editing. We haven’t been able to find anyone who has all of those.”

The tendency to set very stringent qualification requirements in the IT field is mainly the result of rapid technological changes and the consequent proliferation of technological platforms that, once adopted by a firm, must be maintained by professionals with hyper-specialized knowledge or experience (Java versus .NET, for example). As new IT graduates learn the most advanced technologies, and seasoned employees trained in ‘niche’ technologies or even in technologies that are becoming obsolete start to retire, employers face the problem of maintaining legacy systems that newly minted grads may not have learned or may not be interested in working with compared to newer technological platforms. However, sometimes employers can deliberately set very stringent qualification requirements because the candidate pool is large enough that they can be particular. Here is a quotation from a respondent who did not report any hiring difficulties with their IT positions:

- “With our IT positions we get such a large applicant pool that we can get exactly what we’re looking for in terms of preferential experience.”

Formal education, while often preferred, was not generally considered absolutely necessary in IT vacancies. Fourteen percent of IT vacancies included in the survey did not require any formal education at all. Often, specific skill sets and previous work experience were much more important to the employer than the degree of formal credentials.

Where other issues besides skills mismatches were indicated as a challenge, the primary ones were non-competitive wages, low mobility of the workforce, and lack of interest in the nature of the work. The following quotations illustrate these challenges.

- “We pay under-market, and we tend to make that up with bonuses but that doesn’t seem to be a solution for that role.”

- “The unemployment rate in IT jobs is very low. People are still concerned about the economy and stay at their jobs. So people who have skills and experience needed for this position are not moving.”

- “More women need to be encouraged to enter the IT field to increase the pool of available candidates.”

- “This organization doesn’t focus specifically on software engineering, and many people want to work for more innovative firms.”

Strategies such as making IT workplaces more attractive to new STEM graduates (especially women), creating incentives for seasoned employees to stay with the firm, and producing frequently updated career information that advises candidates on in-demand skill sets could be effective ways of addressing some of these problems.

PRODUCTION: High incidence of skills-related hiring difficulties

Hiring difficulties were substantially more prevalent in Production occupations, which included Machinist, CNC Machinist, and Computer-Control Machine Tool Operators. Two out of three vacancies or 68 percent were reported as hard to fill (Figure 1), and skills mismatches alone affected one half of the cases. Unique to Production occupations is the absence of demand-side factors cited as the only reason for recruiting difficulties. As previously mentioned (Figure 6), surveyed Manufacturing employers attributed all hiring difficulties in these occupations to supply issues, either alone or in combination with demand issues.

When demand-side factors were cited as a problem, location2 was the biggest barrier, followed by non-competitive wages and undesirable work shifts.

The following quotations from respondents illustrate these points:

- “There aren’t many people with the required skills and education in this county, so location contributes to our hiring difficulties. There are some qualified people three counties away, but who knows if they are willing to relocate?”

- “Firms steal people from other firms, competing on wage.”

- “We’ve always offered good benefits here, but apparently people are more interested in the pay than in benefits. We might consider offering more money and less benefits.”

- “The job market for machinists is very competitive. There aren’t that many out there compared to demand so they can be choosy on where they want to work and the days/hours of work.”

- “It’s hard to get someone with that level of experience to work on a weekend.”

When supply-side factors were cited as a problem, three main issues emerged: inadequate experience of applicants, inadequate training of applicants, and/or overall low number of applicants for Production openings. Below are some illustrative comments from respondents:

- “Applicants had training, but no practical experience on our machines.”

- “There are trade schools (2-year program for machining) where the lowest level machinist comes from. In our area there aren’t enough qualified machinists because they are being pulled by other machine shops. So we recently started an apprenticeship program to recruit people with some sort of mechanical background and put them through 6-8 weeks of training. We’ll continue running those programs until we get enough people. There is really no end in sight.”

- “At the high school level, students are being pushed to go to a 4-year college program, losing sight of the need for vocational programs.”

- “There are not enough applicants. Blue collar work —factory work — is not what people want. They don’t want to go to school to learn the trades.”

To summarize, employers labeled as skills mismatches the difficulties they encountered when trying to fit the specific experience requirements of a job with the experience profile of candidates. Unfortunately this match is hard to achieve even when supply of qualified labor is abundant. Additionally, the emphasis given to industry-specific experience is bad news for the long-term unemployed, especially if their previous job was in a shrinking industry. The lack of workforce attachment can seriously prevent candidates from demonstrating the relevance of their skills and cannot simply be compensated by holding the right educational credentials.

How serious a problem do skills gaps represent, and what are employers doing about it?

If the impact of skills gaps is severe, we would expect a high proportion of those skills-related, hard-to-fill vacancies to remain unfilled at the time the survey was conducted — typically two to five months after the position was posted. What we see, instead, is that 61 percent were successfully filled, suggesting that most skills mismatches were only a temporary challenge.

When asked which strategies they would use or are already using to respond to hiring difficulties, employers volunteered the following suggestions:

- Make demand more attractive: Offer wages or benefits that are more aligned with competitors; offer more flexible work hours and telecommuting options.

- Enhance internal training: Establish an apprenticeship program; find more effective ways of training internally such as longer orientations, mentorship programs, or on-the-job training so that a new hire without all of the desired qualifications can be brought up to speed.

- Make qualification requirements less stringent: Look at transferable skills rather than hyper-specialized skills; reduce the number of years of experience required.

- Collaborate with high schools and technical colleges: Establish student internship programs to build a pool of pre-qualified candidates.

- Improve recruiting and retention strategies: Recruit new grads from local colleges or advertise on alumni websites; use social media, such as LinkedIn, to attract workers who did not apply for the job; improve internal employee retention so that experienced workers are not lost to other firms.

Enhancing internal training and collaborating with education institutions were the most frequently mentioned strategies, because employers recognize their value. The benefit of partnering with local schools appears to be particularly critical in Greater Minnesota.3

In conclusion, skills gaps are often just the tip of the iceberg of a much broader and more intricate set of factors. There is a need for targeted interventions at various levels of the education system to allow early exposure to careers in skilled trades. Such exposure will increase student interest in technical vocational degrees. Equally important is the role employers can play to improve access for students and job seekers to work-based learning opportunities that develop the most needed skills.

1One quotation illustrates this point: “People want to do development engineering, which is very different from manufacturing engineering. So it’s hard to find people who want to do this work.”

2Location can be problematic either because rural areas are hard to commute to or because semi-urban areas have a high concentration of manufacturers that compete for the same candidate pool.

3One respondent who experienced hiring difficulties commented: “We think it might help to utilize some of our education partners and target schools to see if they have students that are interested in applying. Since part of the issue is our location (hard to get people to relocate or travel) it might help to target the schools in the area.”