by Chet Bodin, Neil Linscheid, Extension Educator at the University of Minnesota Extension Center for Community Vitality; Ben Winchester, Research Fellow, University of Minnesota Extension Center for Community Vitality

Resident recruitment is a term used to describe the complex activities communities are using to attract and retain residents. Community development, creative placemaking, livability – the work of making a city or region more appealing has been called many things. Recently, however, the diminishing supply of labor, which has placed workers and talent attraction at the center of economic development strategies, has led to an evolution of this work. Cities and regions are not only making themselves more attractive but comprehensively marketing elements of workforce development, talent attraction and placemaking to potential newcomers. In support, DEED's workforce strategy team has partnered with the University of Minnesota Extension Center for Community Vitality to amplify the various resident recruitment movements across the state and build a community of practice to identify best practices and develop new ones.

Minnesota is a leader in rural resident recruitment thanks in part to the University of Minnesota Extension's pioneering rural movers research, which is focused on finding out why people move to rural areas. Extension has worked for over a decade to disseminate those findings to rural communities throughout Minnesota and across the country. Those communities used the findings to expand and coordinate their local and regional economic development efforts with community development and tourism – resulting in today's comprehensive resident recruitment initiatives. Since Extension first shared this information a decade ago, many such resident recruitment initiatives have sprung up organically across the state. No other state has a network of resident recruitment initiatives like those in Minnesota.

Though no formal, in-depth study has been done to gauge the effectiveness of the resident recruitment initiatives, numerous testimonials1 and the local prioritization of these efforts suggest they are worthwhile. Leaders of local and regional initiatives point to an increase in diverse investments from public, private and nonprofit sources in recognition of their value. These investments have led to more coordinated and effective marketing and communications efforts that are raising awareness about the benefits of living and working in those communities. Erik Osberg, Rural Rebound coordinator in Otter Tail County, remarked that "Awareness is the first step in resident recruitment. These public/private partnerships have allowed our county to position themselves as a top-of-mind choice when potential workers are thinking of a rural place to live."

In this article, we describe the context, trends and patterns of community action related to resident recruitment in Minnesota. Overall, the pattern we observe is that Minnesota communities and regions have been experimenting with resident recruitment activities for the past two decades and that those activities built critical capacity across the state to continue innovating in resident recruitment activities.

Given that 85% of cities in Minnesota have fewer than 5,000 residents, attracting residents, particularly those who add to the regional workforce, has gained prominence as an important aspect of economic development activity. Historically, the predominant strategy of bringing in new residents was through job creation via industrial recruitment and attraction. Cities across the state have long funded economic development staff whose primary focus is leveraging state and federal resources to improve critical infrastructure to allow for industrial expansion. The common belief was that attracting industry would bring new residents who follow the jobs. However, economic and community development practitioners have begun to recognize that industrial recruitment is a non-starter when a community lacks the workforce needed.

Talent attraction, on the other hand, has typically been left to employers and their human resource practices, whose focus on the job can overlook components of livability and accommodation that drive potential residents' decision-making processes. If recruitment ends when a new resident opens the door to their new home, business and community leaders miss opportunities to engage potential entrepreneurs, future local officials and volunteers. This can be especially critical for the smallest communities which struggle to retain the critical mass of engaged citizens needed to fully execute their development plans.

Additionally, most communities in Greater Minnesota face unique demographic challenges that are driving the shift to resident recruitment. In the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area, talent attraction is crucial to retaining businesses and remaining one of the top locations for corporate headquarters. But in Greater Minnesota, where a high proportion of youth leave for urban education and job opportunities, talent attraction is even more urgent and nuanced. Newcomers don't just move to Greater Minnesota for work or education, which is often the case in metro areas. Instead, people who move to Greater Minnesota communities often do so for public safety, outdoor recreation, less traffic and other reasons which are at least as important to them as work opportunities.

In a tight labor market, jobseekers can find work in their field of choice almost anywhere, but if they move for a position, their life outside work may be very different depending on where they choose to live. This makes quality of life as important as availability of jobs when attracting residents.

For small and medium-size cities across the state (and the country for that matter), honing their resident recruitment strategy, and embracing the potential for change that accompanies it, may very well determine the economic future of their community.

When utilized as a complementary approach to economic development, resident recruitment strengthens regional development strategies. But the traditional pretext that people only move to a new community for a job has proven to be less instructive over time. This shift has led to further research on what attracts new residents, and the importance of sharing the results for the benefit of communities in Minnesota that seek to foster a welcoming and engaging local climate.

In 2019 the University of Minnesota Extension undertook a study to further explore the motivations of people who moved to rural Minnesota. This study was conducted through a survey of households that moved to a new zip code across rural Minnesota between one and five years ago. Throughout this article we will refer to this as the Rural Movers Study. This study is a follow-up to Extension's pioneering earlier migration research, which showed that people in their 30s, 40s, and 50s have been moving to rural communities for a slower pace of life, safety and security, as well as the lower cost of housing.

We have called this in-migration to rural areas the "brain gain". This terminology comes in response to the negative "brain drain" narrative that's so often associated with rural communities. The "brain drain" is described as a pattern whereby high school students, upon graduation, move away in search of employment, education, or life experiences. Based on our research we know that this trend has less to do with the local community and more to do with the stage of life of these young people. Young people want to explore the world and find their place in it. However, this terminology characterizes rural communities as faulty, uninspiring places decimated by population loss where success is improbable if not impossible. Interestingly, this negative narrative is not unique to rural areas. Across Minnesota, anywhere from 25% to 65% of high school graduates leave their home community – including metro areas – for other pursuits.

Although they might be the most visible, high school graduates are only one part of the rural migration story in Minnesota. People, primarily in their 30s through 50s have been choosing to move to rural communities for decades. These people are in their prime earning years, have work experience, education, social connections, and a different perspective on small town life than they may have had in their 20s. It's this consistent trend that we've labeled the "brain gain".

The 2019 Rural Movers Study showed that 31% of movers indicated they were moving due to a job or job offer. People typically need a source of income, of course, but gainful employment was not one of the primary reasons people chose to move to their new community. In fact, a good environment for raising children, living closer to relatives (for those returning to a previous home), safety and security, a slower pace of life, and the low cost of housing were the top factors cited by newcomers in the location of their home. Of those not moving for a job, the top factors identified for choosing their destination community are the following:

| To find a good environment for raising children | 76% |

| To live closer to relatives | 67% |

| To find a safer place to live | 64% |

| Take advantage of the slower pace of life | 64% |

| To live in a smaller community | 64% |

| To find a less congested place to live | 60% |

| To find lower priced housing | 58% |

| To find higher quality schools | 58% |

| To buy available land | 56% |

| To find a job that allowed a better work-life balance | 54% |

| Source: UMN Extension Rural Movers Study, 2019 | |

The Rural Movers Study found that just 25% of newcomers to a community had lived there before and were now returning (returnees). Looking at that another way, three-quarters of new residents had not previously lived in their destination community. This raises even more questions for rural community leaders who are developing resident recruitment programs: What resources helped with the move? Do newcomers feel a sense of belonging? Do they believe the community is welcoming? How's this experience different for someone who has historical familial ties to a community compared to that for truly new residents?

In addition, respondents were also asked if they are likely to be living in the community in five years. When we break out the welcoming community agreement by this likelihood, we find a pretty clear relationship - when a community is perceived as being welcoming residents are more likely to see themselves there in the future. A full 86% of those who felt the community is welcoming believed they would be likely to still be living there in five years.

| The Community is Welcoming | Likely to Live Here in 5 Years |

|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 86% |

| Agree | 77% |

| Disagree | 68% |

| Strongly Disagree | 44% |

Based on the results from the Rural Movers Study, its clear that a job-first approach to community resident recruitment in not enough. Several factors, beyond job considerations, are also important for resident recruitment activities. Rural communities who want to recruit residents need to help people envision rural communities as safe places to raise children, with more affordable housing, where newcomers can plant roots, refocus, and have more opportunity to enjoy life outside of work.

These results point to a new view of resident recruitment that does not begin with employment. Aspects of community development, economic development and tourism all play a role in recruiting new residents to a region. This model of resident recruitment involves the coordinated economic and community development actions needed to identify, attract, invite and welcome new residents to the region.

Community leaders rightly wonder what options they have to address a decline in people of working age and lack of young families in their community. Whether they view demographic change as a challenge or an opportunity, the slate of actions available to them is similar. They can choose to do nothing, take action to recruit new residents, and/or find ways to retain residents that want to remain in their community. Unfortunately, lack of action is still the norm in many communities. The interest, motivation, and impetus to take collective action around resident recruitment may not be sufficient to drive an organized effort.

Communities that have decided to do something to recruit residents have taken a variety of strategies. We can view this slate of resident recruitment strategies along a continuum with one pole representing ad hoc efforts and the other representing fully-funded, strategic and multichannel recruitment programs. Ad hoc efforts represent organic and emergent activities often done by volunteers to welcome or recruit new residents. For example, a group of volunteers who take it upon themselves to be the community's welcoming committee, which might conduct informational community tours for prospective residents. Ad hoc efforts can be found in nearly every community, but due to their informal nature might be challenging for potential residents to identify and utilize.

Fully-funded strategic multichannel recruitment efforts represent the other end of the spectrum. These types of efforts are operationally housed within a community backbone organization such as a chamber of commerce, economic development organization, nonprofit, tourism promotion organization, or community foundation. This type of effort has dedicated staff, strategic and operational plans, and resources to carry out resident recruitment plans. The efforts are multichannel because they have a portfolio of activities that frequently include branding, advertising, engagement, coordination and program management functions. Advertising activities often take the form of integrated place branding campaigns which attempt to create a brand for the region or community, then apply that brand to websites, printed materials and other advertising. The engagement activities that this type of effort conducts include engaging directly with recent newcomers or potential residents through concierge-like programs or regularly scheduled events for newcomers. Engagement activities can also include efforts to engage area employers in the resident recruitment process. The coordination and management of this type of effort involves negotiating the needs of multiple stakeholders in the service region. This might include, in the case of a regional effort, working with leaders from multiple communities to identify community assets, resources and goals, followed by coordinated implementation of a shared vision for resident recruitment.

Community-driven resident recruitment efforts have evolved over the past two decades and continue to innovate. The variety of resident recruitment efforts means that it's difficult to identify clear middle areas in this continuum of activities. Some efforts are organized around a single program such as a newcomer welcoming committee and manage that effort effectively, while another effort might focus solely on community branding and marketing efforts, and not engage directly with potential residents. In Minnesota, this means there is no such thing as a standard or ideal resident recruitment program – these programs and activities are context-specific.

There are arguments to be made about the need to coordinate resident recruitment at both local and regional levels. In fact, local placemaking efforts often complement each other in a way that can and should be packaged in a regional marketing strategy. That said, local officials may prefer that a new resident chooses their specific community – for a lot of good reasons. New residents represent more local spending, workers and human capital. However, the regional nature of commuting, shopping and leisure in rural areas have an important influence on newcomer trends. Whether it's for work or play, traveling 30 miles in a rural area is much different that in an urban one.

When looking at resident recruitment through the lens of economic development, these regional trends make a strong case for collaboration among local officials from neighboring communities. In counties outside the Seven County Metro Area, a full 57% of workers commute more than 10 miles, and nearly a third drive more than 25 miles to work. This commuting reflects a further decoupling between home and work. In 2018 just 51% of Minnesota workers are working in their home county.2 In other words, an influx of new residents, whether to your community or the neighboring city (or the one next to that), will increase each community's ability to draw in new businesses, especially those that require a large workforce and generate sizable tax revenues.

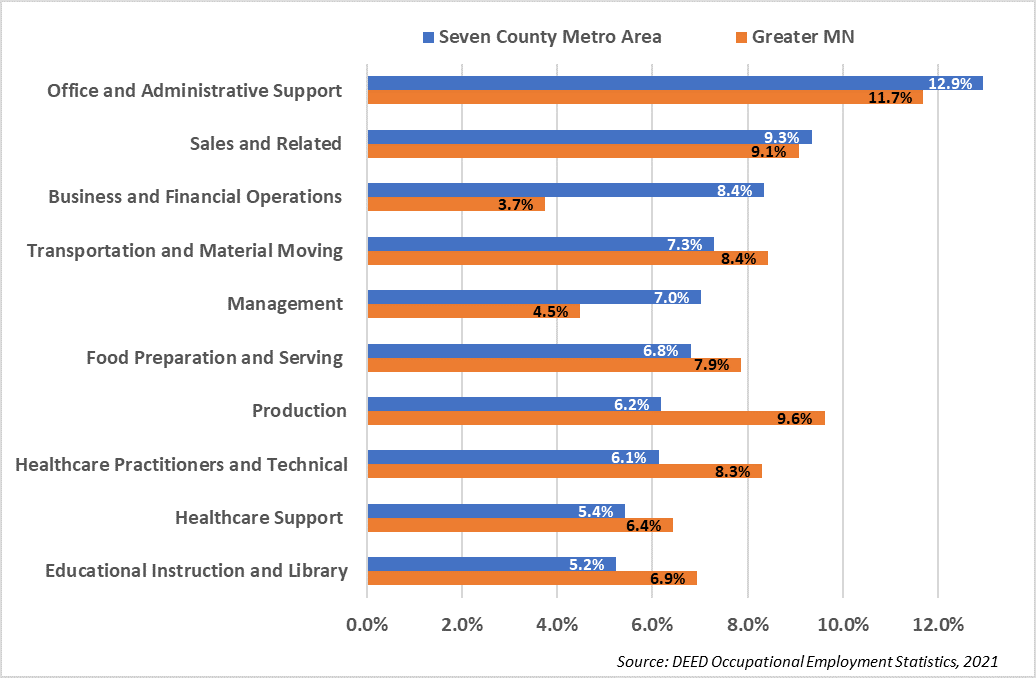

Alternately, regional efforts also allow local developers to leverage the occupational diversity of a region and attract residents who may work elsewhere. Small to mid-size towns often struggle with the 'lack of opportunity' narrative, but this argument becomes less powerful in a regional context. At the regional level, Minnesota's rural economy displays a wide range of opportunities, and in some ways is even more diverse than the Seven County Metro Area. In fact, six of the top ten occupational groups in the metro area are proportionally more prominent in Greater Minnesota (see chart 1). While these jobs are more dispersed, longer commutes do not appear to be as much of a concern in Greater Minnesota.

Although most resident recruitment initiatives started at the local level, it's evident that no one city or town can develop every career path within its borders, nor should they have to. Similarly, industrial clusters are less bound by political borders than by geography, which often spans vast areas. With this in mind, several communities in Minnesota are collaborating on regional resident recruitment efforts, even if they also have a local program. Some have even decided to abdicate industrial development to larger regional centers and focus on livability. These are but a few examples that demonstrate how resident recruitment programs across the state are evolving – an innovative community of practice that sets Minnesota above its peers in today's economic development environment.

Developers across Minnesota are already doing this well and finding support from public and private partners. The University of Minnesota Extension has chronicled this work as it has evolved and local areas experiment with new techniques. Over time, financial support for these efforts has grown significantly from nonprofits, foundations, private industry and local governments.

For example, the "Get Rural" recruitment initiative in western Minnesota, housed at the Upper Minnesota Valley Regional Development Commission in Appleton, started with motivated EDA staff, city clerks and regional development agents dedicating their time. This was a shift in workload, not necessarily the development of a new group or agency. One advantage of this initiative was the existence of the Arts Meander regional arts tour that had already been well established in the region and provided an experienced team to grow the initiative. Success has inspired more research, innovation and other regional partners to join them.

In Otter Tail County, a welcoming initiative for newcomers was so instrumental it led to a full-time staff person funded by local tax dollars. Others have worked alongside local employers to market the community at job fairs and with other outreach campaigns.

While there are likely more, DEED and the University of Minnesota Extension have identified 12 local resident recruitment programs and seven regional initiatives throughout Minnesota. (See Figure 1). Some of these efforts are small and led by local government or nonprofit staff who have a limited amount of time to spend on the work. Other projects are large, well-established efforts with private investment and fully-dedicated staff.

People choosing to move to communities in rural Minnesota are motivated by factors beyond jobs, such as community amenities, opportunities for social life and many others. The evidence compiled by the University of Minnesota Extension and demonstrated by communities across the state is far more compelling than the anecdotal arguments that informed industrial recruitment strategies of the past. As the competition for labor heats up across the nation, resident recruitment efforts and innovative practices will help communities and regions of Minnesota – as well as the state as a whole – stand out as great places to work and live.

1See testimonials on these resident recruitment initiative websites:

2U.S. Census Bureau, Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics (2018)