by Alessia Leibert

June 2022

Current workforce shortages in Greater Minnesota are primarily caused by population and labor force participation declines. This article documents the challenges of workforce retention in Greater Minnesota among college-age individuals and examines the role that high school Career and Technical Education (CTE) can play in mitigating them.

The decision to remain close to home after high school can be very personal, including lifestyle preferences, proximity to family, and commuting distances. Still the most powerful incentive is often the pull of economic opportunity. High school graduates are more likely to move to places where hiring is stronger and jobs are better paid. They also tend to gravitate towards places that give them better chances of attaining a postsecondary education. Therefore, the geography of jobs for students five years after high school tells a story about local hiring demand and overall opportunities available to young Minnesotans close to home.

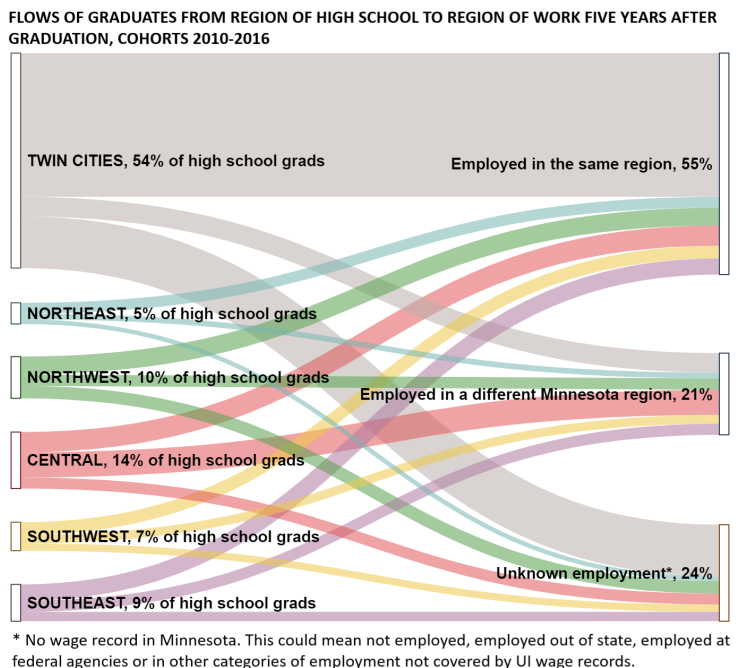

When considering all high school students five years after graduation, one out of five (21%) public high school graduates1 had jobs outside the region of schooling and nearly one out of four (24%) did not have an employment record in Minnesota (Figure 1). Regions are defined in this study as Planning Areas.

Although lack of a wage/employment record has many possible explanations2, the most likely explanation among college-age individuals is having left the state for school or work. In fact, of the 24% of graduates without employment records, at least half (51%) enrolled in a postsecondary school outside Minnesota at some point during the first five years after high school graduation3. According to the Minnesota State Demographic Center, between 2008 and 2012 two-thirds of Minnesota's total annual net loss of residents is due to students leaving for higher education, and far fewer return in the post-college years4.

The current study is based on 336,319 students who graduated from a Minnesota high school between 2010 and 2016. In these years, the Twin Cities region accounted for 54% of public high school graduates, most of which were working in the same region five years after graduation. High retention rates are attributable to the region's high concentration of postsecondary schools, businesses, and jobs. In contrast, Greater Minnesota lost a large share of graduates to other regions or to other states. Without more people entering the labor force to replace those who leave, employers in Greater Minnesota will have to invest in labor-saving technologies, relocate to another region, or close.

The study considers the following research questions:

Career and Technical Education (CTE) is a term applied to educational programs/courses that integrate core academic knowledge with technical and occupational skills to provide students a pathway to postsecondary education and careers. CTE is not a program, but a constellation of programs administered and delivered independently by each school district, which decide how much to invest in programming and how to partner with local employers and postsecondary schools.

This decentralized model leads to substantial geographic variation in CTE participation rates. Researchers distinguish between four main levels of participation: students who take over 150 hours of instruction in a single CTE career field (commonly referred to as CTE concentrators); students who take over 150 hours but not in a single career field; students who take less than 150 hours; and students who do not take any CTE courses in high school. For our first research question we will compare concentrators to everyone else.

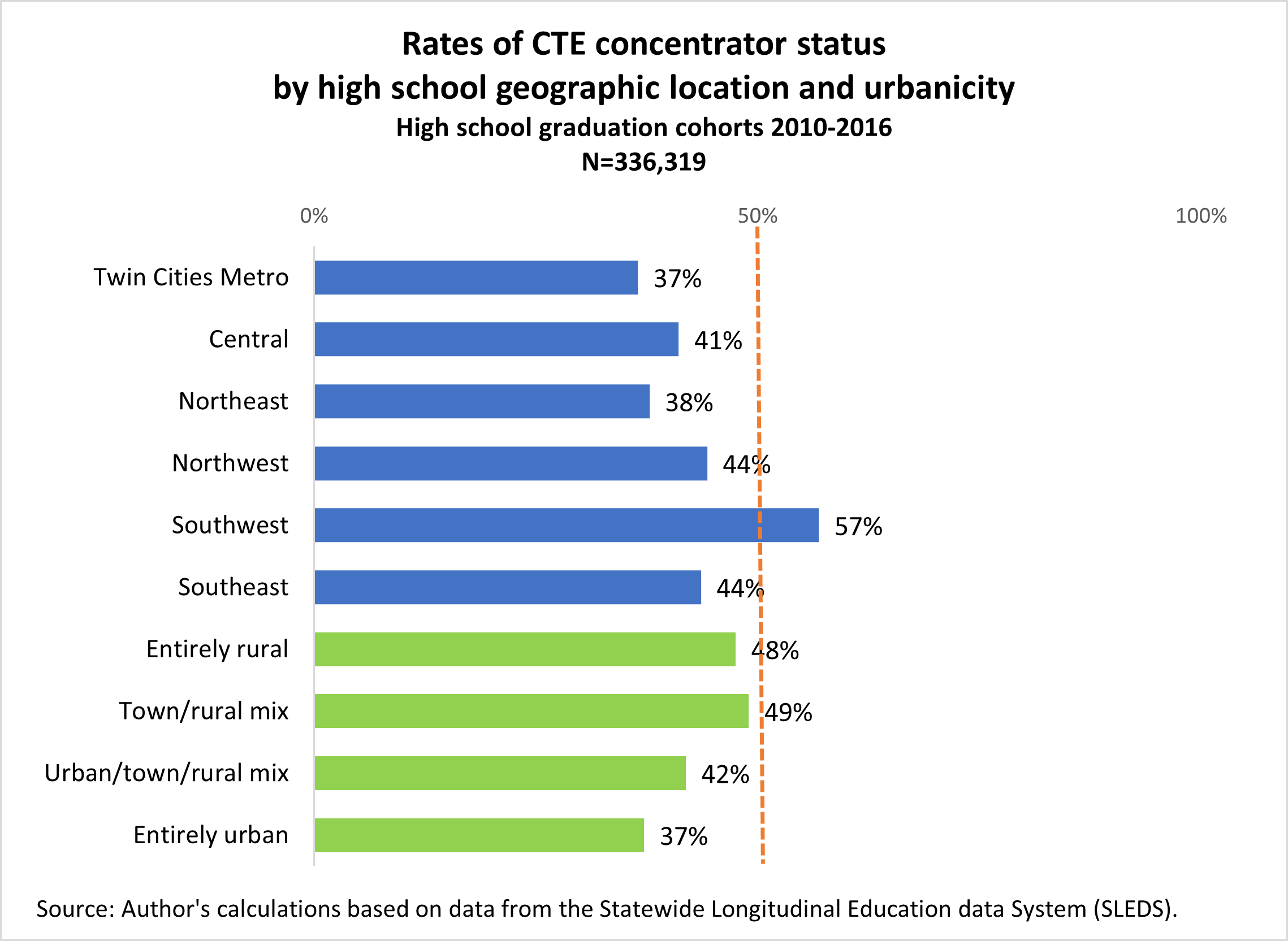

In the 2010-2016 cohorts, rates of CTE concentrator status ranged from 37% in the Twin Cities to 57% in Southwest Minnesota (Figure 2). This implies that a student who graduated from a public high school in Southwest Minnesota was much more likely to be a CTE concentrator than a student who graduated from a school in the Twin Cities.

These results are strongly influenced by the degree of urbanization of the county in which a school is located. Schools in rural or town/rural mixed counties have higher rates of CTE concentrator status (48% and 49% respectively).

Retention rates by region, already presented in Figure 1, are reproduced in greater detail in Table 1.

What jumps out immediately are the low retention rates in Greater Minnesota regions, especially Central Minnesota which had only 35% of graduates employed locally five years after high school. The main challenge facing Central Minnesota is its close proximity to the Twin Cities, where wages, amenities, and educational opportunities are attractive features for many students5. The Twin Cities region has the highest youth workforce retention rates of all, at 67%.

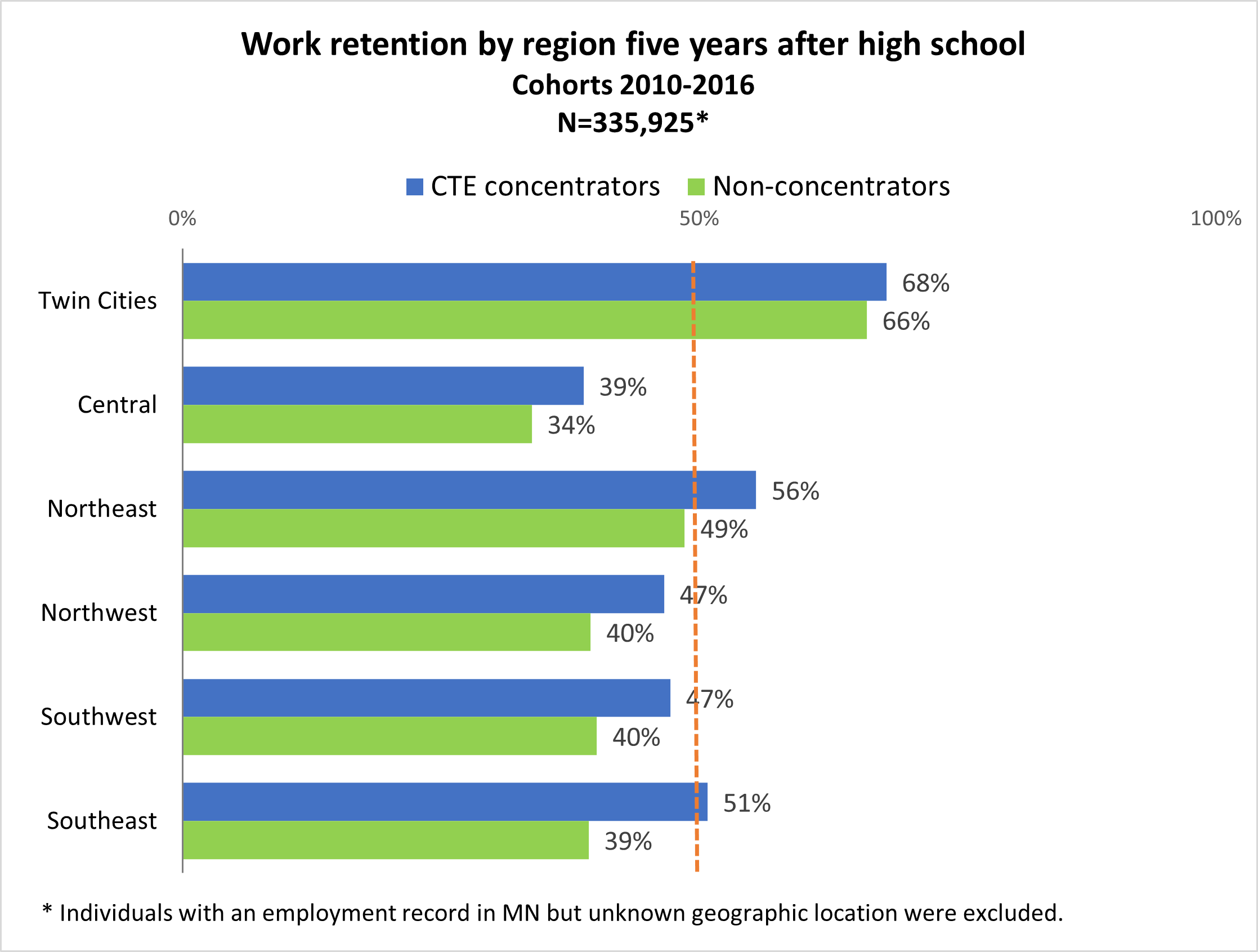

Figure 3 below displays the first data column from Table 1 and breaks the information into two groups: CTE concentrators (blue) and all other students, labeled here as non-concentrators (green) for further description and analysis.

Across geographies, CTE concentrators were more likely to be employed locally five years after high school. This is particularly evident in the three regions where concentrating in CTE was most common during the study years: Southwest, Southeast, and Northwest. The region with the largest gap in retention rates between concentrators and non-concentrators is Southeast (51% versus 39%).

How can we be sure that these encouraging results are attributable, at least in part, to high school CTE and not to other factors that influence a student's decision to stay? A regression analysis demonstrates that CTE concentrators were significantly more likely to be employed in the same region also when other variables are accounted for, including academic proficiency in middle school, economic status, demographic and school characteristics6. This suggests that high school CTE is a promising local workforce retention strategy.

After having ascertained that high school CTE contributes to greater local retention among CTE concentrators, the next question to address is: how is this being achieved? What might be the mechanisms through which CTE is contributing to higher retention?

Students' decisions to stay or move is influenced by many factors, including the following:

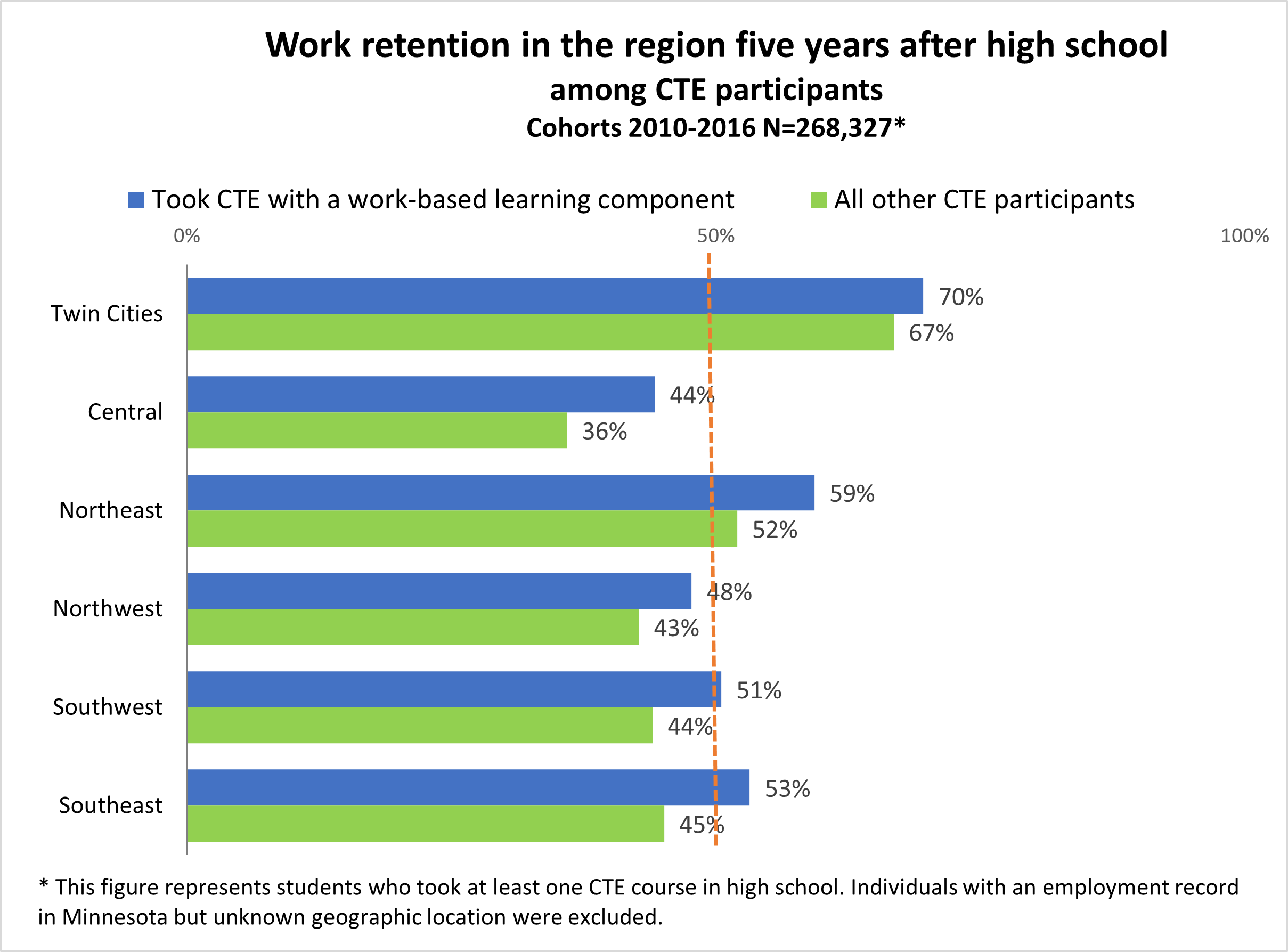

The first CTE course feature contributing to higher retention is work-based learning, including on-the-job training, internships and apprenticeships. With few exceptions, CTE electives are the only high school courses offering these opportunities. Figure 4 shows how students who participated in CTE courses with a work-based learning component were more likely to become employed in the same region compared to other CTE participants. This is particularly true in Greater Minnesota, where maximizing retention is an imperative.

The likelihood of remaining in the same region for work among CTE participants who took work-based learning (blue bars) is even larger among students who completed apprenticeships or on-the-job training, which represent real job placement experiences for students. Table 2 shows how three Greater Minnesota regions – Northwest, Southwest, and Southeast – are on the forefront of offering exposure to real-world workplaces to Minnesota students through CTE.

Offering work-based learning opportunities not only adds relevance to classroom instruction, but also connects students to local employers encouraging them to remain in the region for work. Therefore, integrating work-based learning into CTE programs is beneficial not only to the employment trajectory of students but also to the local business community as a whole.

The second factor contributing to retention – enrolling in a local postsecondary school – may appear unrelated to CTE, but it is actually of the utmost importance to CTE's mission. A big part of CTE funding has been directed towards establishing well-articulated course progressions – called Programs Of Study – to strengthen the alignment between secondary and postsecondary CTE programs, as well as establishing articulation agreements allowing students to earn college credits through CTE and utilize them to complete a credential at a local college. Through these initiatives, CTE can greatly encourage students to attend local postsecondary schools.

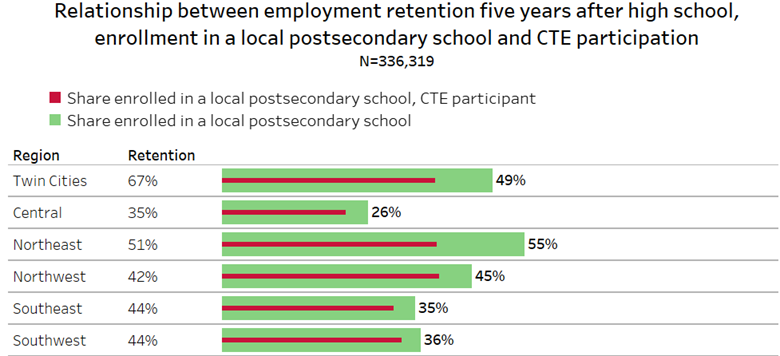

In the absence of a measure that can identify students who received articulated credit at a local community college through CTE, we developed a measure for whether students (and CTE participants in particular) enrolled in postsecondary school in the same region as their secondary school (Figure 5).

The relationship between enrollments in local postsecondary schools (the green bars) and work retention is extremely strong. Central Minnesota, the region with the lowest share of students enrolled in local postsecondary schools (33%), has the lowest retention, while the Twin Cities and Northeast, regions with the highest shares of students enrolled locally (49% and 55% respectively), have the highest retention. The red bars show that, in each region, the majority of students enrolled in a local postsecondary institution participated in CTE. Since CTE participants' ability to avail themselves of postsecondary enrollment opportunities is a stated goal of CTE programming, we can conclude that the integration of high school CTE with college-prep academic coursework is definitely a feature worth investing in to incentivize students to remain in their region longer.

To wrap up this discussion, it is worth bearing in mind that some regions are at a disadvantage regardless of how hard they try to increase students' uptake of opportunities for work-based learning or local college enrollment. Central Minnesota is emblematic in this regard. The region invested heavily in CTE programming, offers students plenty of opportunities for work-based training through CTE, has a long tradition of collaboration between secondary and postsecondary schools7, and is not an education desert. Yet it has the lowest workforce retention rates five years after graduation, at 35%. This undesirable outcome is possibly a consequence of the region's close proximity to the Twin Cities, which generates competition for workers and students8.

The third feature of CTE courses that can contribute to improved retention is the degree of alignment between CTE programs and the needs of regional economies. The stronger the alignment between CTE programs and the occupational/industry profile of a region, the greater the likelihood that students will connect with local employers to jump start their careers (or education) locally. This analysis does not aim at quantifying alignment between CTE course offerings and local jobs. Rather, it aims at documenting the variation of students' course-taking patterns by region and investigating the relationship between such variation and the unique characteristics of regional economies in Minnesota. Table 3 shows considerable regional variation in the mix of CTE courses taken by students.

The first takeaway from this analysis is that, across regions, the subject area that attracted the largest shares of CTE concentrators is Business & management, with percentages ranging from 21% in Southeast and Southwest to 30% in the Metro. The popularity of these courses stems from the breath of course offerings, ranging from accounting to marketing and business law.

The second takeaway is that CTE course-taking patterns (thus, presumably, course offerings) are, by and large, tailored to the needs of local economies. More students seem to enroll in courses that offer more opportunities to find jobs locally. The most notable examples are:

This evidence shows that high school CTE has been adapted regionally to help build the local talent pipeline in key industry sectors. At the same time, however, we also notice imbalances between the popularity of certain fields with students and local demand in occupations associated with these fields. Follow up analysis suggests that, during the study years, more students enrolled in programs in Agriculture compared to local jobs in agriculture-related occupations. The opposite problem is represented by Education, which had nearly zero enrollments in our cohorts despite high demand for workers with a background in education. Additional programs in Education were introduced too recently for students in the 2010-2016 cohorts to be able to take advantage of. This gap was partially compensated by the fact that students who took Family and Consumer Sciences (FACS) courses had opportunities to study Early Childhood Education, although evidence shows that only 12% of FACS concentrators were employed in the Education industry seven years after high school graduation.9

Other glaring gaps are in Information Technology and Health care, which support numerous local jobs and yet attracted fewer students than fields with declining employment such as Fashion, Apparel, Interior Design (FAID) & photography10. Such gaps could be filled through improvements in career advising services to students and through stronger partnerships with local employers to help ensure that curricula are aligned with industry needs.

The evidence presented in this study suggests that investments in high school CTE can help sustain regional labor force growth and thus mitigate workforce shortages in Greater Minnesota. Here is a summary of findings:

High school CTE represents an important economic development and workforce retention tool. More should be done to engage local employers, as well as existing postsecondary partners, in order to increase the number of CTE courses earning both high school and postsecondary credit. This, along with increasing local work-based learning opportunities, would serve to attract students towards critical workforce pipelines.

This research uses data on students who graduated from a Minnesota public high school merged with postsecondary student records and Minnesota Unemployment Insurance wage records from the Statewide Longitudinal Education Data System (SLEDS). All students who graduated from high school between 2010 and 2016 are included except GED completers, those who graduated after age 20, and those who participated in special education services in grade 11 and 12. Finally, since the study's main goal is to measure the role of CTE course-taking behavior on outcomes, we only included students who had a record in grades 10th, 11th, and 12th to be able to observe their complete course-taking pattern.

1Throughout the article, students who received special education services in the last two years of high school were excluded because their likelihood of participating in covered employment is low. See "About the data" text box for other exclusion criteria used in this study.

2Including unemployment, not seeking employment, employment at federal agencies or in small agricultural businesses, and self-employment.

3Source: National Student Clearinghouse accessed through the Statewide Education Data System (SLEDS). This measure partially undercounts out-of-state enrollment because some postsecondary institutions do not report to the National Student Clearinghouse.

4From Minnesota on the Move: Migration Patterns & Implications, January 2015 (based on data from the American Community Survey), page 14.

5To confirm this hypothesis, we found that, of the 45% of students who attended high school in Central Minnesota and did not became employed locally, 72% became employed in the Twin Cities.

6A logistic regression model predicting the probability of an individual to be still employed in the same region of secondary schooling revealed that CTE concentrators have a positive and statistically significant probability of being employed in the same region relative to non-concentrators with similar characteristics. The model controls for a rich set of variables including gender, race, eligibility for special ed services at any time in K-12, eligibility for free/reduced price lunch, disability status, English language learner status, speaking a language other than English at home, attendance in 8th grade, math and reading proficiency in 8th grade, and others. These results are robust to different model specifications and to the inclusion of measures of postsecondary enrollment status.

7One example is the Senior to Sophomore program at St. Cloud State University education.

8According to the US Census Bureau 2009-2013 estimates, corresponding to the years of interest in this study, nearly one-in-five (19.1%) workers resident in the Central Minnesota Planning region in 2014 travelled to Hennepin County alone.

9See Females in Career and Technical Education, pages 11-12

10For a detailed analysis of the employment and earnings outcomes of students who concentrated in this field of study see Leibert, Females in Career and Technical Education, pages 9-12.