by Michael Darger (University of Minnesota Extension), Ashley Petel*, Cameron Macht (DEED), Joshua Hebeisen*, Caleb Reed*, Joseph Dragotta*

* students at the University of Minnesota

March 2024

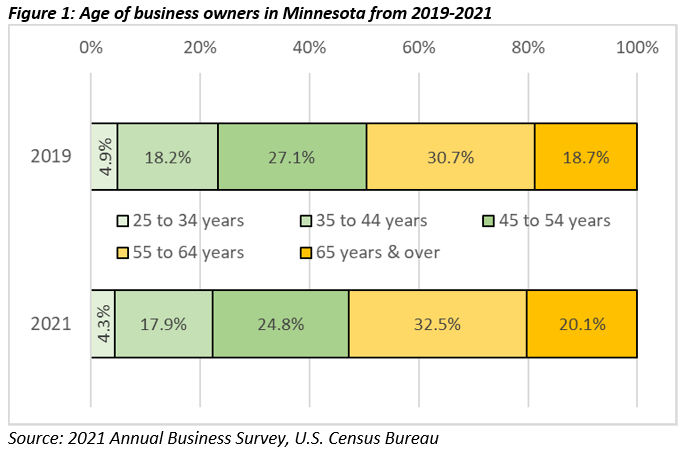

While the ages of owners and businesses change every year in small businesses, the combination of those two factors is well worth studying. According to a report from the Minnesota Center for Employee Ownership, in Minnesota there are an estimated 50,000+ businesses with owners aged 55 years or older. Likewise, according to the 2021 Annual Business Survey from the U.S. Census Bureau, nearly 53% of businesses had owners who were 55 years and over. This is notable because the share of business owners in the oldest age groups has increased over time, with that trend accelerating in recent years (see Figure 1).

The Annual Business Survey also shows that Minnesota has a higher reliance on long-time businesses, with more than 40% of businesses operating for 16 years or more, which is over 8% more concentrated than the U.S. overall. These long track records suggest these businesses are successful and will continue to enhance Minnesota's economic vitality (see Table 1).

Table 1: Age of businesses in Minnesota and the United States

| Years of Business Firms | Minnesota | United States | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| Total | 112,176 | - | 5,893,424 | - |

| Firms with less than 2 years in business | 12,619 | 11.2% | 867,040 | 14.7% |

| Firms with 2 to 3 years in business | 11,888 | 10.6% | 769,902 | 13.1% |

| Firms with 4 to 5 years in business | 9,082 | 8.1% | 582,449 | 9.9% |

| Firms with 6 to 10 years in business | 18,890 | 16.8% | 1,017,756 | 17.3% |

| Firms with 11 to 15 years in business | 13,525 | 12.1% | 715,279 | 12.1% |

| Firms with 16 or more years in business | 46,169 | 41.2% | 1,940,998 | 32.9% |

| Source: 2021 Annual Business Survey, U.S. Census Bureau | ||||

Using this same Annual Business Survey data, we can assess some further demographic details of business owners in the state. The largest percentage of business owners identified as white alone, and not Hispanic, accounting for over 85% of total businesses in Minnesota. In comparison, about 76% of the state's total population reported white alone as their race, and not of Hispanic or Latino origin.

It's important to note that race data was not available or reported for almost 6% of business owners in the survey, which may reflect people of some other race or two or more races, which combined make up about 7.6% of our population. Asian and Other Pacific Islanders accounted for just over 5% of the state's total population and just over 4% of business owners. Black or African American residents make up almost 7% of our population, but just 2% of business owners in the state. People of Hispanic or Latino origin comprise 5.7% of the state's population, but own only 1.3% of businesses in the state according to the Annual Business Survey. And finally American Indian and Alaska Natives account for the smallest share of population and business ownership, at 0.9% and 0.5%, respectively (see Table 2).

Table 2: Minnesota Business Ownership Statistics by Race or Ethnicity, 2021

| Race/Ethnicity | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 112,176 | - |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 96,088 | 85.7% |

| Black or African American | 2,110 | 1.9% |

| American Indian & Alaska Native | 513 | 0.5% |

| Asian | 4,460 | 4.0% |

| Equally minority/nonminority | 1,106 | 1.0% |

| Hispanic | 1,419 | 1.3% |

| Not classified | 6,480 | 5.8% |

| Source: 2021 Annual Business Survey, U.S. Census Bureau | ||

Another interesting facet of ownership is gender. Annual Business Survey data show about 60% of businesses in Minnesota were owned by males, just over 22% were female-owned, and about 16% were owned equally by males and females, with data not available for another 2% of businesses. These shares held relatively consistent across owner tenure, with one notable exception: females make up a higher share of new businesses that have been around for 5 years or less (see Table 3).

Table 3. Minnesota Business Ownership Statistics by Gender, 2021

| Years of Business Firms | Total | Male | Female | Equally Male/Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| Firms with less than 2 years in business | 12,619 | 7,442 | 59.0% | 2,807 | 22.2% | 2,255 | 17.9% |

| Firms with 2 to 3 years in business | 11,888 | 7,166 | 60.3% | 3,302* | 27.8%* | 1,420 | 11.9% |

| Firms with 4 to 5 years in business | 9,082 | 5,215 | 57.4% | 2,188 | 24.1% | 1,679* | 18.5%* |

| Firms with 6 to 10 years in business | 18,890 | 11,182 | 59.2% | 4,176 | 22.1% | 2,997 | 15.9% |

| Firms with 11 to 15 years in business | 13,525 | 8,369 | 61.9% | 2,603 | 19.2% | 2,121 | 15.7% |

| Firms with 16 or more years in business | 46,169 | 27,510 | 59.6% | 6,718 | 14.6% | 5,868 | 12.7% |

| Total, Firms | 112,176 | 66,884 | 59.6% | 25,096 | 22.4% | 18,019 | 16.1% |

| Source: 2021 Annual Business Survey; * - calculated; numbers do not sum to 100% due to non-available data | |||||||

The future of these businesses is a critical economic development topic that will affect communities across the state. Business succession and transition planning is a process where business owners prepare for their departure with a plan to transfer their business to new ownership and leadership. Keeping these businesses open when owners or leaders move on is an important opportunity for Minnesota, especially in rural communities. In many cases, small businesses are the lifeblood of small towns, and research shows that after a succession event, new leadership of the businesses tend to hire more employees and increase sales.

University of Minnesota Extension has provided research and education to communities on business retention and expansion (BRE) for many years. This practical activity is a fundamental part of economic development because most new private sector jobs are attributable to existing businesses. As part of this work, Extension assists communities in their efforts to support businesses through the succession and transition process. In 2023, the Extension team embarked on a research project to explore business owner awareness, attitudes, aspirations and action on succession and transition planning. The goal of this research is to inform the public and private sectors on barriers and gaps in the ecosystem for helping businesses transfer ownership.

This research involved administering a paper survey through U.S. mail in spring 2023, using a four-wave methodology informed by Don Dillman's Tailored Design Method. A scientific sample was created and nearly 300 valid responses were received from small business owners and leaders in Minnesota. Most respondents had the joint role of owner and senior leaders (84.6%), but some were only leaders (10.1%) or only owners (3.8%).

The survey included questions for business owners and leaders about their awareness of, attitudes towards and action taken on business succession and transition planning. Many questions relied on a Likert scale in which respondents answered the question with a 1 to 6 rating, 1 indicating "not at all" and 6 indicating "to a great extent." The Likert scale questions asked about degree of agreement, familiarity, likelihood, importance, or readiness. In analysis, average ratings were calculated to investigate general responses while ratings were grouped for a deeper look at the data (e.g. 1-2 as not familiar, 3-4 as somewhat familiar, and 5-6 as familiar). We received 286 survey responses, usable for analysis. The full descriptive statistical results of the survey.

The average age of respondents was 59, with a range from 33 to 90 years old. Approximately 66% of respondents were aged 55 and older, which is higher than the estimated 53% of owners aged 55 and older in Minnesota (see Figure 1). Approximately 72% of respondents identified as male, 26% as female, and less than 1% as non-binary. Participating businesses came from across Minnesota, with 72% in urban areas (207 businesses) and 28% in rural areas (79 businesses). A majority of the respondents were white (95%) while few respondents identified as American Indian or Alaska Native (1%), Asian (1%), or Black or African American (1%). Less than 1% of respondents identified as Hispanic or Latino.

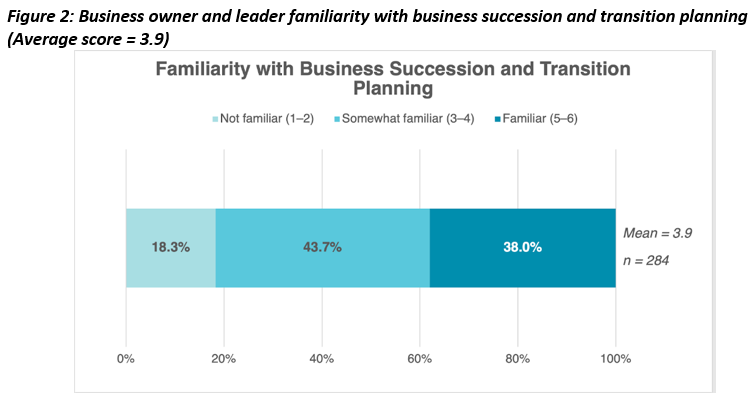

Respondents indicated how familiar they are with business succession and transition planning (see Figure 2). A large portion of respondents are somewhat familiar with planning for business succession and transition (43.7% rating a 3 or 4 on a 6-point scale from "not at all" familiar to familiar "to a great extent"). A much smaller share of respondents are not familiar (18.3% rating a 1 or 2) while more than one-third of respondents considered themselves familiar with the process (38% rating a 5 or 6).

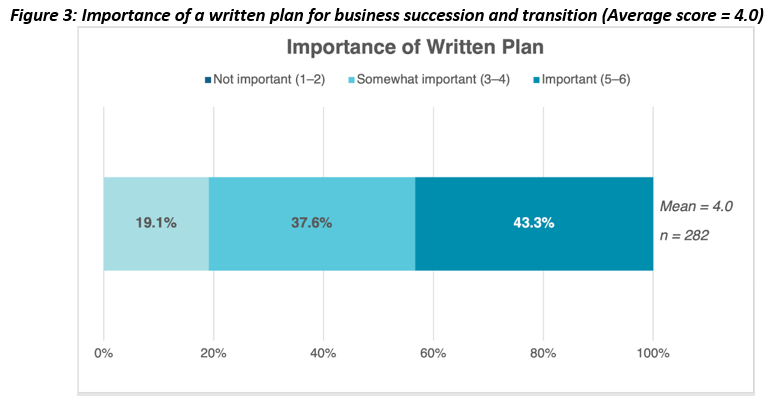

Respondents were asked how important they believe a written plan is for business succession and transition (see Figure 3). A majority believed that a written plan was important (43.3%) or somewhat important (37.6%). Just 19.1% of respondents believed that a written plan is not important. However, only 19.2% of respondents reported creating or updating a written business succession and transition plan within the last three years. Furthermore, 60.8% of respondents indicated they spend less than one hour per week planning for business succession and transition.

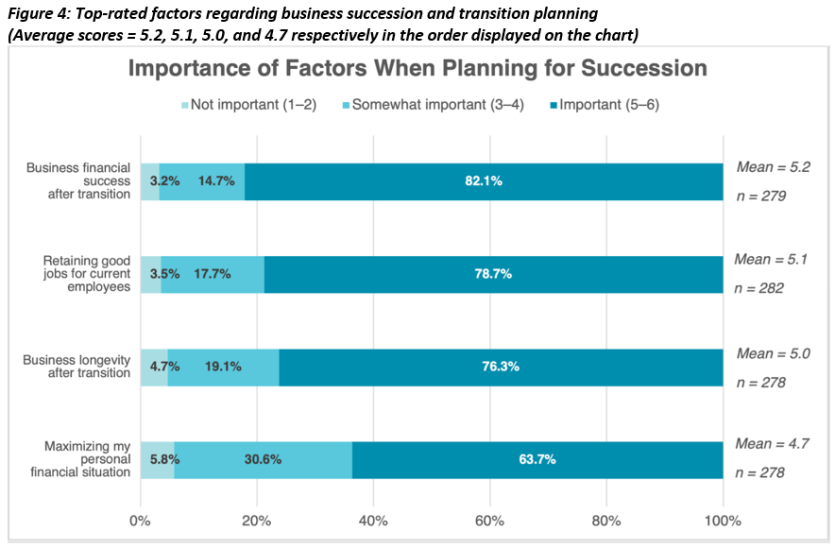

Business owners and leaders responded to questions that asked how important different factors are with regard to their planning for succession and transition. In the first instance (question 11), they rated the factors on a 6-point scale. In the second instance (question 12), they ranked the top three most important factors. The factors with the highest average rated scores mostly matched those with the highest rankings: business financial success after transition, retaining good jobs for current employees, business longevity after transition and maximizing their personal financial situation (see Figure 4 and Table 4). It should be noted that two other factors received high average rankings yet they were ranked by many fewer respondents.

Table 4: Which three factors below are the most important to you? (Rank 1st, 2nd, and 3rd)

| Factor | Importance – Owners that ranked it 1st, 2nd, or 3rd | Average Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| Business financial success after transition | 176 | 1.7 |

| Retaining good jobs for current employees | 138 | 2.2 |

| Maximizing my personal financial situation | 136 | 1.6 |

| Business longevity after transition | 121 | 2.3 |

| Keeping business in the family | 64 | 1.9 |

| Keeping business in the community | 60 | 2.2 |

Looking at these factors from the perspective of a community economic development professional offers unique insights. Three of the four top factors that business owners and leaders value are key concerns of communities: business financial success after transition, retaining good jobs for current employees, and business longevity after transition. Other factors relevant to communities that owners were asked about included keeping the business in the community and adding new jobs in the future.

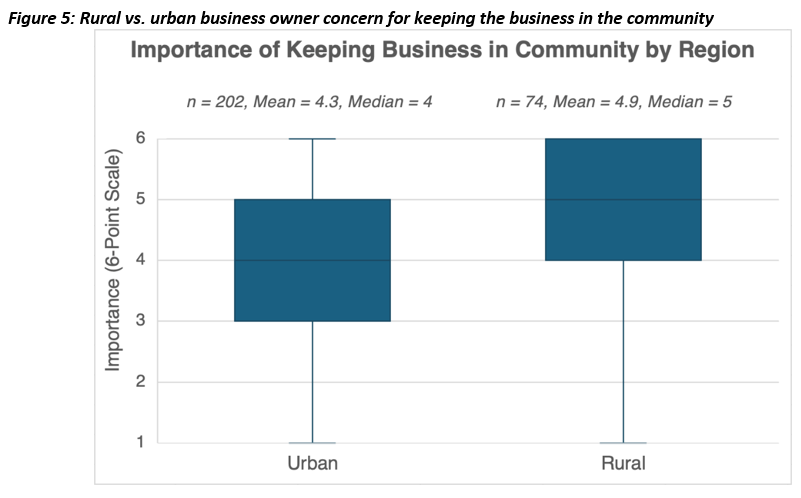

Interestingly, rural business owners were highly correlated with increased concern for keeping the business in the community (p-value 0.002; see Figure 5). Rural communities tend to be more concerned about the retention and expansion of businesses. If a community has only one grocery store or manufacturer or funeral home, it is a big deal if that business leaves. Additionally, older business owners are correlated with more concern over business longevity after transition as an important factor (p-value 0.016) and adding new jobs in the future (p-value of 0.05).

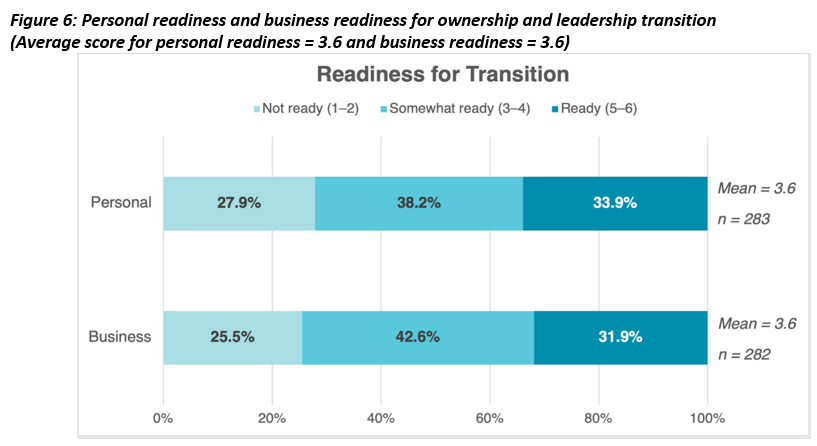

Respondents were asked to identify how ready they were personally to step away from the business and how ready their business was for an ownership and leadership transition (see Figure 6). Average readiness for both questions was 3.6. Approximately one-third of respondents are personally ready for transition (33.9%), 38.2% are somewhat ready, while 27.9% are not personally ready to step away from the business. Similarly, 31.9% of respondents believe their business is ready for transition, 42.6% believe it is somewhat ready, while 25.5% believe their business is not ready for succession.

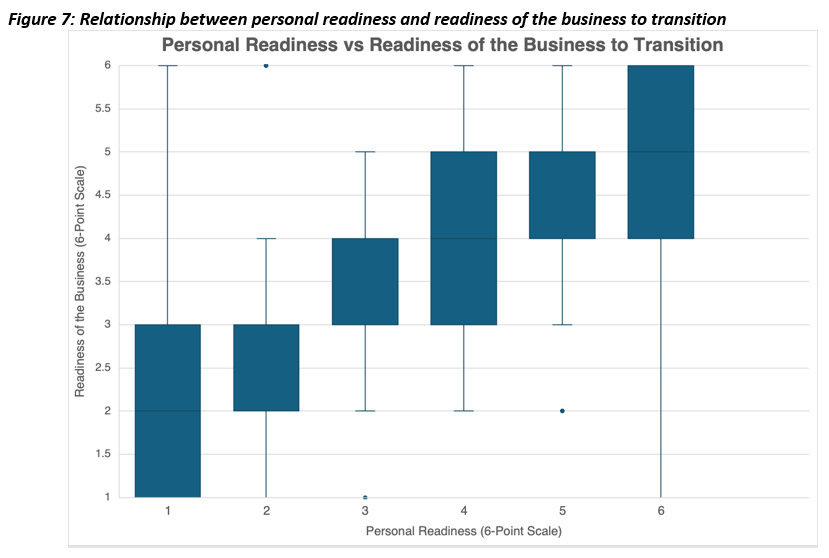

A compelling trend emerges when analyzing the relationship between a business owner's personal readiness and the readiness of their business to transition (see Figure 7). Notably, as the personal readiness of the owner increases on the 6-point scale, so does the readiness of their business for transitioning ownership. This upward trajectory suggests a positive correlation between personal readiness and business readiness.

The answers to these readiness questions are correlated with answers to other questions in the survey. For example, there is evidence of a meaningful relationship between personal readiness and seeking advice and resources from a partner/spouse (p-value of 0.005). Additionally, personal readiness is correlated with having family discussions (p-value of 0.021), engaging in discussions inside the business (p-value of 0.049), and obtaining a formal business valuation (p-value of 0.04996).

Business readiness is correlated with seeking advice and resources from a partner/spouse (p-value of 0.006), from an attorney (p-value of 0.019), and from an accountant (p-value of 0.035). Separately, certain preparation actions that business owners take are correlated with higher scores on business readiness, including the following: creating or updating a written succession and transition plan, obtaining a formal business valuation, having family discussions, and training a successor (see Table 5). These are confirmatory findings because these activities are associated with successful transition planning in the academic literature.

Table 5: Succession and Transition planning activities that are highly correlated or correlated with business readiness

| Planning Activity (from highest to lowest correlation) | p-value |

|---|---|

| Creating or updating a written succession and transition plan | 0.0005 |

| Obtaining a formal business valuation | 0.0010 |

| Having discussions with family members | 0.0037 |

| Starting training a successor | 0.0263 |

To that end, past research on succession and transition planning has found that owners and leaders find it easier to let go of their business if they have a plan for what they will do next. Extension's research seems to confirm this. The respondents were asked if they had plans for retirement. The survey found a statistically significant relationship between a business owner or leader's personal readiness and working part-time or full-time elsewhere after stepping away from the business (p-value of 0.047), and if the owner is unsure about their next steps after leaving the business (p-value of 0.011). The readiness of the business is correlated to working part- or full-time after parting ways with the business (p-value of 0.037). However, there was no correlation with personal or business readiness when a respondent indicated they would fully retire.

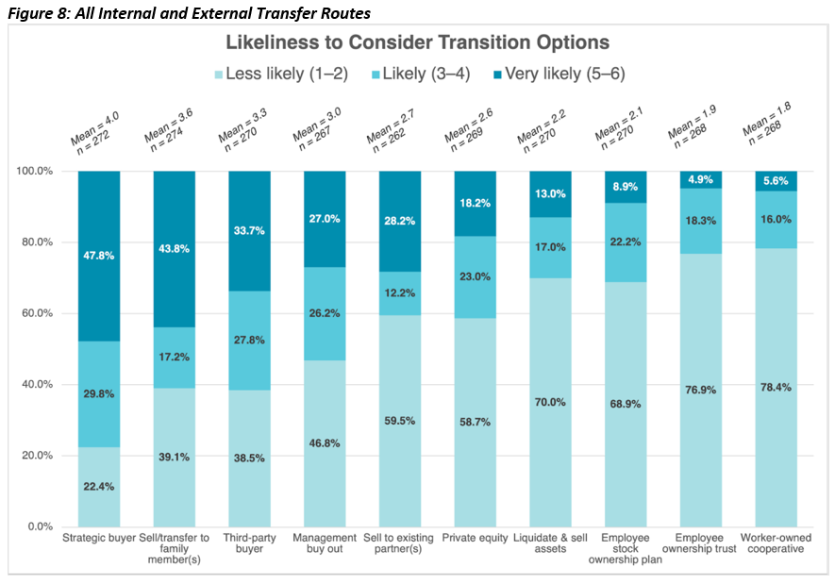

The survey explored awareness of and intentions for ten different routes for the transition of business ownership. Four options are external, that is selling to buyer(s) outside of the business. Six options are internal, that is selling to family members (of the owner), or employees, partners, or managers in the business. With regard to intentions for transfer (question 21) there were only two very likely routes and several less likely routes. In the very likely range, only selling to strategic buyers (i.e., a buyer from the same industry or sector) (average score 4) and selling/transferring to family members (3.6) received scores above the midpoint on the 6-point scale (1 = not at all likely and 6 = to a great extent).

In the likely range were: third-party buyer (i.e., an investor or entrepreneur) (3.3), management buy out (i.e., selling to existing management) (3), sell to existing partner(s) (2.7) and private equity (i.e., capital investment made into privately held companies) (2.6). In the less likely range were all three forms of employee ownership: employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) (2.1), employee ownership trust (1.9) and worker-owned cooperative (1.8). In fact, all forms of employee ownership were less likely than liquidate and sell assets (2.2) (see Figure 8).

Some of the factors referred to in Figure 4 above (question 11) were found to be predictive of certain transfer routes (question 21) using ordinal logistic regression. Maximizing their personal financial situation was strongly correlated with likeliness to transfer to either a strategic buyer or private equity (p value < 0.001). Retaining good jobs was correlated with management buyout or employee ownership trust (p value < 0.01).

Only one of these correlations was true in the opposite direction. When strategic buyer was the independent variable, maximizing their personal financial situation was strongly correlated. This is not a surprising result because business transition experts will point out that buyers from the same industry are typically willing to pay the highest price for a business. For economic developers and other community officials, the news here is that some transfer routes align with owner priorities that also can be beneficial for the community (i.e. retaining good jobs being correlated with management buyouts and employee ownership trusts).

The results from this research will inform future efforts at Extension and beyond. The data and findings are valuable to a wide swath of people, which can be organized into messaging relevant to specific audiences. Different segments of this data can inform each of these audiences in their involvement with business succession and transition planning. These audiences include:

The data from this research project offers a glimpse into what business owners are thinking about regarding business succession and transition. Business owners may be interested in knowing what their peers are thinking about this topic, how they are preparing for succession, who they are consulting with and what pathways they are considering. This message can be shared with business owners through classes, chambers, newsletters, networking and more.

Many insights from the survey results can support efforts and decision-making of community economic development professionals supporting business succession planning. Data relevant to this population include correlations with personal and business readiness, perceived barriers to planning for succession, advisers and resources that business owners find trustworthy and how business owner priorities align with community economic development efforts. Efforts taken may include building awareness, connecting business owners with advisers, facilitating connections between business owners' priorities and the transition options and providing resources to create and update written succession and transition plans.

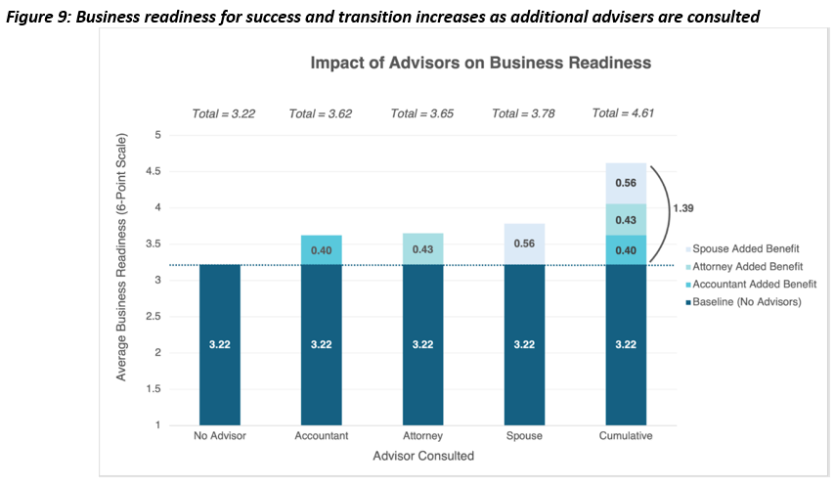

Business advisers such as accountants, attorneys, financial planners, spouses and other business owners can play integral roles in business succession planning. The results show that the more advisers a business owner consults, the higher they score on personal readiness and business readiness for transition. For every additional adviser a business owner uses to aid their business succession and transition planning, their expected level of personal readiness increases by approximately 0.125 units, and business readiness increases by approximately 0.162 units on a 6-point scale.

Notably, there are specific advisers that are correlated with a dramatic increase in business readiness: spouse (0.56 units), attorney (0.43 units) and accountant (0.40 units; see Figure 9). If no advisers are consulted, the expected business readiness is 3.22 on a 6-point scale. However, if a spouse, attorney and accountant are consulted on business succession and transition planning, the business readiness is expected to increase to 4.61 on a 6-point scale. Based on these findings, Extension has begun discussions with accountants about this topic to involve them in the effort to support business owners to plan for succession and transition.

Employee ownership models offer a unique alternative to traditional business models and serve as a viable pathway for business succession and transition. Three main types of employee ownership exist in the United States: Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs), worker-owned cooperatives and employee ownership trusts. Awareness, expertise and financials have been identified as barriers to implementing employee ownership models.

This research explored business owners' awareness of and attitudes toward employee ownership models. Future publications from Extension will highlight these findings. As shown above in Considering Transfer Routes, the three forms of employee ownership were unlikely transfer routes and were even less likely than owners liquidating the business. It is the opinion of the lead author that employee ownership is an underutilized pathway for retaining and expanding Minnesota businesses. Future research may investigate this topic more deeply, including employee awareness of and attitudes toward employee ownership. In Minnesota, the Minnesota Center for Employee Ownership and the Employee Ownership Working Group network are leading the charge to increase awareness and resources around employee ownership.

Certain data relevant to this audience includes questions about business owners' familiarity with and likelihood to consider transitioning to an employee ownership model. Additionally, certain segments of the business owner population may be more inclined to consider employee ownership, and this data may help identify owners who may be interested in discussing employee ownership for their situation.

Supporting business succession and transition is a critical community economic development strategy to ensure that small and local businesses remain an integral part of Minnesota's economy. To assist business owners and economic developers in their efforts to retain companies and jobs in their communities, a concerted, widespread support system is needed. This research highlights that business owners need to increase their awareness and engage with resources to support their planning for business succession and transition.

Endnote on statistics: