by Carson Gorecki and Cameron Macht

March 2024

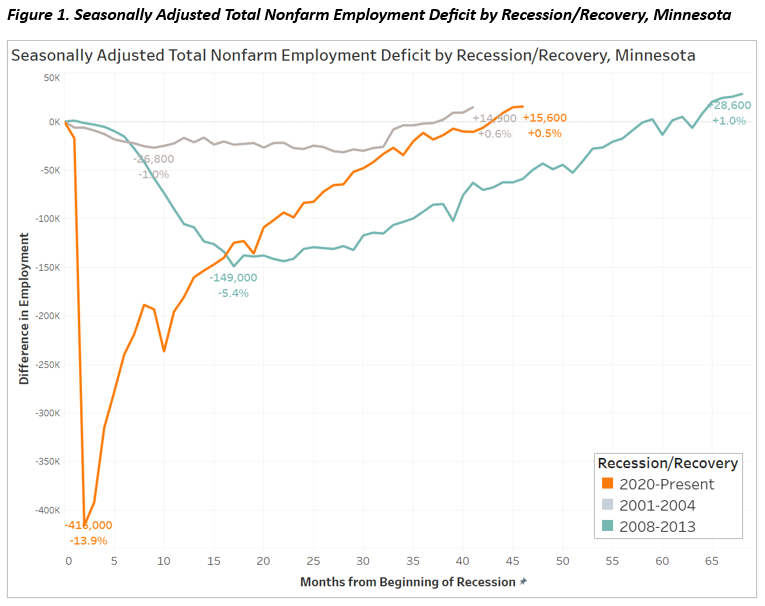

Minnesota along with the rest of the nation has experienced three recessions since 2000, with widely varying levels of job loss and recovery. The 2001 "dot-com" recession was mild but still took about three years to get back to growth. The Great Recession in 2008 was much more severe and lasted around five years, but then led to one of the longest running economic expansions on record. And while every recession is unique, the Pandemic Recession was completely unprecedented. Between February and April 2020, Minnesota lost 416,000 jobs – nearly 14% of employment vanished virtually overnight as the world shut down in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (see Figure 1).

Since then, there have been many articles covering the nature and magnitude of this historic employment decline in Minnesota and how it impacted the labor market and different industries. This article and its charts will detail how, almost four years later, employment has now surpassed pre-pandemic levels and has returned to growth. It is important to note that while statewide total employment has regained the jobs lost in the first quarter of 2020, by that same measure some industry sectors and metropolitan areas have not fully recovered and are now on new paths.

In Minnesota, it took 43 months to gain back the 416,000 jobs lost over those two months in spring 2020. The rate of employment growth began strong, with almost 230,000 (55%) of those jobs returning by October 2020. That was good enough for an employment growth rate of 8.8% over six months, or the average addition of 37,900 jobs per month. However, there was a second dip in November 2020 as COVID-19 surged in Minnesota, before job growth began again.

From that point on, until September 2023 when employers surpassed pre-pandemic levels, the rate of employment growth slowed to 7.3% over 35 months, or an average monthly addition of just under 5,840 jobs. That would be rapid growth in normal times, especially considering the average number of jobs added per month for the two years leading up to February 2020 was just over 2,620 jobs. Even with substantially slower job growth compared to the rapid recovery in 2020, Minnesota's economy continues to grow more than twice as fast as it did leading up to the Pandemic Recession.

The previous two recessions also provide interesting contrasts to the trends seen over the last four years. The Great Recession crested in Minnesota in 2009 with a peak job loss of 149,000 jobs, or a decline of 5.4% relative to the month before the recession began. The dot-com recession of the early 2000s had an even smaller decline of 31,500 jobs, or 1.2% total. And while the dot-com recession and subsequent employment recovery took a little over three years, the Great Recession and recovery took five years and four months. After the Great Recession began in spring 2008, it was not until the end of the summer 2013 that employment surpassed the pre-recession level of 2,767,000 jobs.

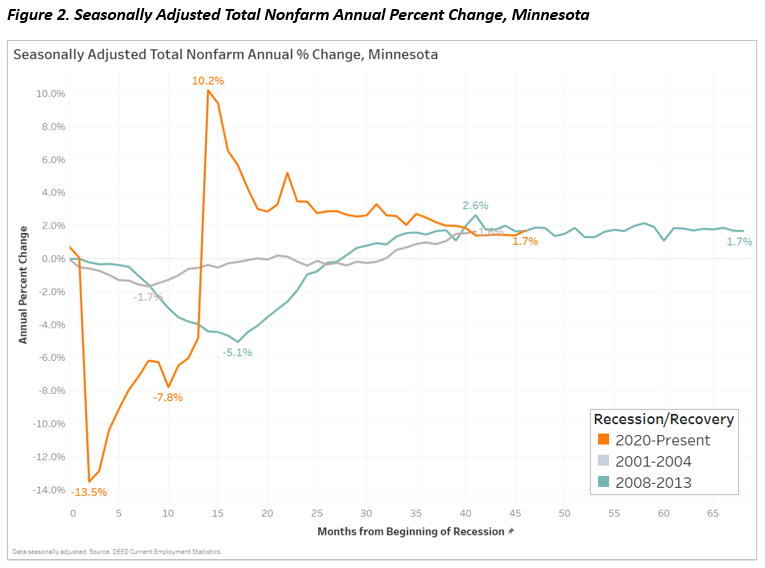

The differing shapes of the last three recessions and recoveries are also notable. The Great Recession exhibited a clearly defined decline, followed by a steady recovery that gained speed over time. The first year following the employment low of September 2009 saw annual employment growth of 0.6%, then annual employment growth over the next three years averaged 1.9%. The trend for the dot-com recession and recovery was less well-defined. The employment low point occurred in November 2003, 28 months after the start of the recession, which also included several periods of slight growth. From that low point, it was less than a year before pre-recession employment levels were reached.

The much larger swings experienced in the most recent recession are visible in the total employment trends chart shown in Figure 1. But those swings are highlighted in a different way in Figure 2 by comparing the over-the-year percent employment change. The close proximity of the minimum (-13.5%) and maximum (+10.2%) annual percent change in the pandemic era emphasize the acute fall and quick turnaround toward recovery (see Figure 2). In contrast, the two previous recoveries did not see annual employment change climb into positive territory until about two years after their starts.

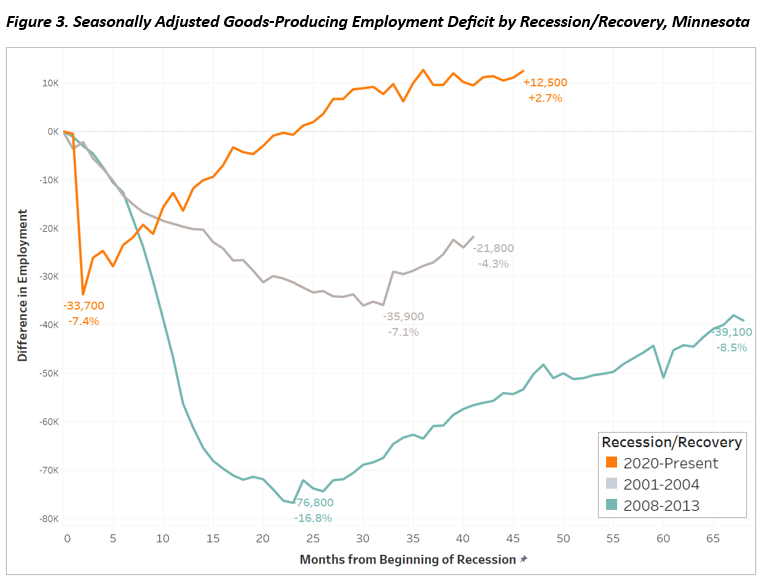

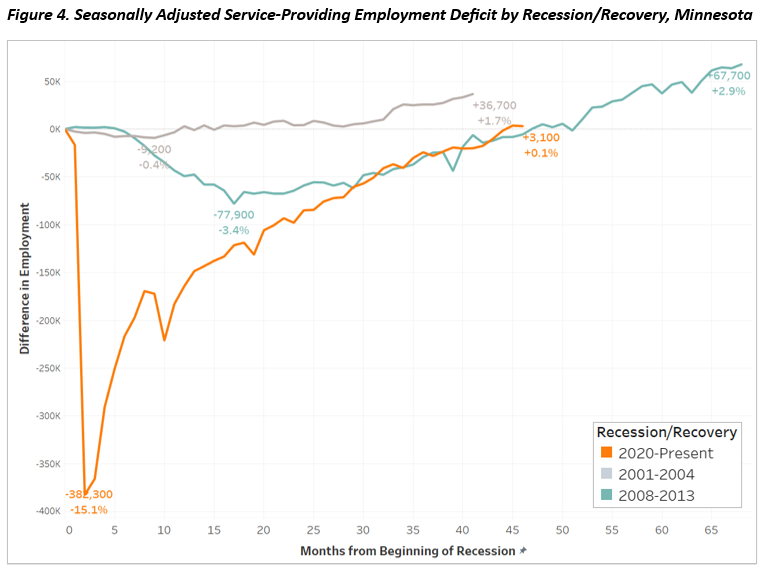

The variations in the Pandemic Recession and recovery by industry are also worthy of attention. The type of activity performed often dictated how vulnerable a given industry or sector is to employment losses during a recession, as well as how it responds after the initial employment shock. The Pandemic Recession provides a good example of this.

The largest distinction during the Pandemic Recession is between goods-producing and service-providing industries. Historically, recessions were much more likely to negatively impact employment in goods-producing sectors like Construction and Manufacturing. The most recent recession flipped this script. It was service-providing sectors like Leisure & Hospitality, Education & Health Services and Other Services that saw the largest declines, while Manufacturing and Construction were two of the best performing sectors.

The maximum employment decline for all goods-producing sectors during the Pandemic Recession and recovery was 33,700 jobs (-7.4%), all of which was regained within two years (see Figure 3). As of December 2023, goods-producing sectors were up by 12,500 jobs (+2.7%) in Minnesota. The two previous recessions and recoveries both saw larger numeric losses. In both instances, the goods-producing domains failed to regain pre-recession employment levels by the time each recession was officially declared over.

In contrast, service-providing sectors, which account for about 85% of all jobs, both declined more rapidly and recovered more slowly than their goods-producing counterparts in the Pandemic Recession. Whereas goods-producing employment in the current recovery took 24 months to reach pre-pandemic levels, service-providing employment required an additional 21 months to reach that milestone. In comparison, the dot-com recession and recovery saw less than a year of employment deficit in the service-providing domain, but the Great Recession actually took three months longer to reach total employment recovery than the Pandemic Recession recovery (see Figure 4).

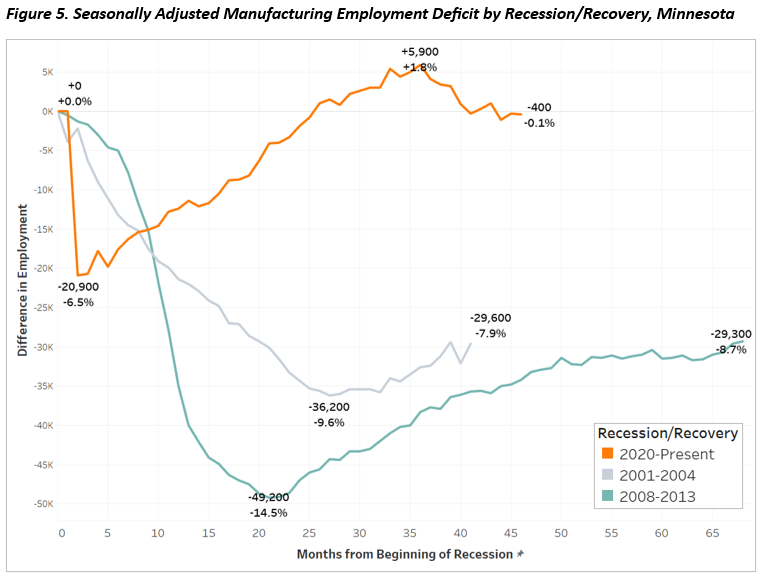

Since the onset of the Pandemic Recession, Manufacturing employment in Minnesota has experienced a notable resurgence, marking a positive trend amid economic challenges. Manufacturers posted a record number of job vacancies in 2022, and labor availability remains a concern, although the outlook shows improvement compared to previous years. Respondents to a DEED survey on manufacturing business conditions indicated they expect to see modest expansion in profits, number of orders, productivity and product and service production levels in 2024. Coming out of a recession, this growth is both weird and welcome.

Unlike past recessions, it took just over two years for Minnesota's Manufacturing firms to regain pre-pandemic employment levels. And while there has been a recent employment decline in the sector, Manufacturing remains one of the best-performing areas of the state economy over the pandemic period. After losing nearly 21,000 jobs initially in 2020, the sector netted 26,800 additional jobs in under three years. Manufacturing growth over that period was almost 800 jobs added per month. That stands in stark contrast to the past two recessions, when Manufacturing employment dropped severely and never fully recovered (see Figure 5).

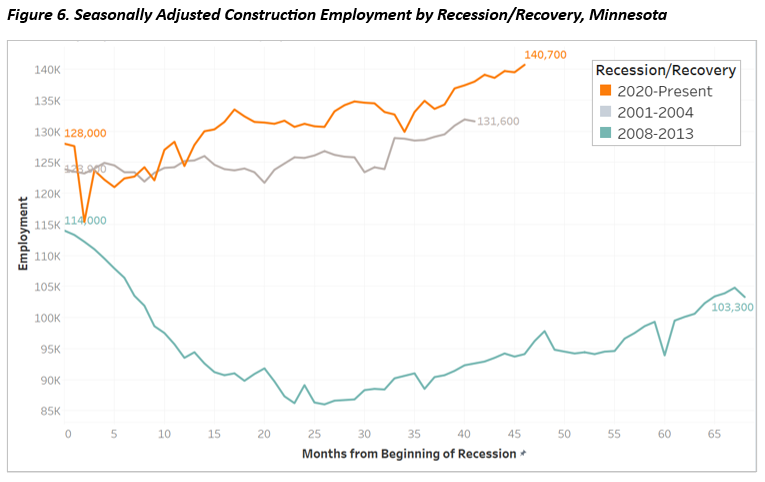

While Construction was the canary in the coal mine of the Great Recession, already starting to lose employment from 2006 to 2007; it has been the trailblazer of the current recovery. Construction has gained nearly 13,500 more jobs since 2020, up nearly 11.0% (see Figure 6). Recent growth has ensured the strong run continues for the sector. Just over the last year, the state saw the addition of 10,800 Construction jobs. The 8.3% annual growth rate in December 2023 was lower than only two months in mid-2021, which represented the earliest recovery growth from the lowest employment levels. By comparison, Construction employment fell further and remained significantly below pre-recession levels in both the two previous recessions years after their onsets.

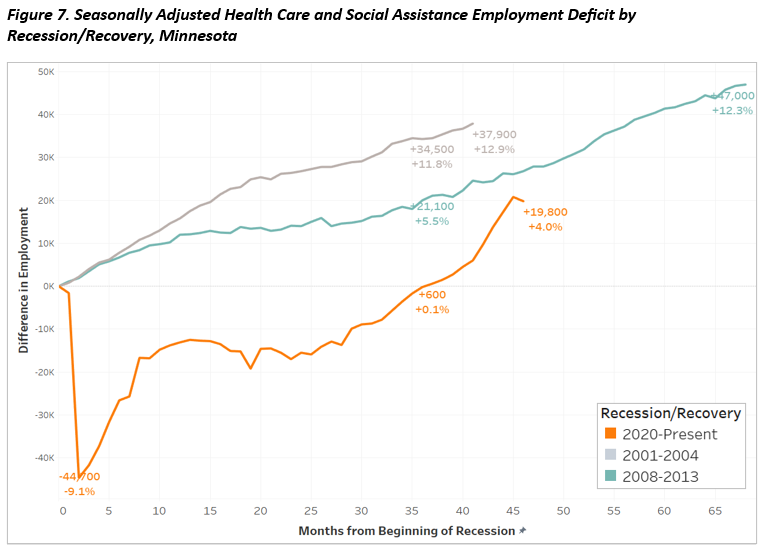

In contrast, Minnesota witnessed a notable decline in employment within the Health Care & Social Assistance sector during the Pandemic Recession. The initial employment shock led to the loss of nearly 45,000 jobs (see Figure 7). That was immediately followed by a period of rapid growth resulting in the addition of 28,000 jobs in half a year. That growth proved to be short-lived as only 8,900 jobs were added over the next two years. Employment growth in the sector picked up again more recently. In December 2023, the annual percent change was 4.8%, well above the 1.7% growth for total employment.

As the COVID-19 crisis unfolded, stringent lockdown measures and the prioritization of essential services significantly impacted the demand for non-emergency medical care and social support services. Consequently, many health care facilities and social assistance organizations faced financial strain, leading to layoffs, furloughs and reduced hours for workers across the state. The shift towards telehealth and remote social services further reshaped the employment landscape within these sectors, with delivery models and locations changing.

In addition, many people employed in the industry supersector left employment over the course of the pandemic due to burnout, health concerns about COVID-19 and higher wages in other industries, leading to job loss due to lack of people to fill open positions (Minnesota's Health Care Employment Amid a Pandemic, September 2020 Minnesota Economic Trends, Minnesota's Direct Care Workforce, June 2023 Minnesota Economic Trends). Despite gradual economic recovery efforts, the enduring effects of the pandemic continue to influence employment patterns within Minnesota's Health Care & Social Assistance industries. This is different from past recessions, when Health Care & Social Assistance just kept adding jobs regardless of the state of the economy (see Figure 7).

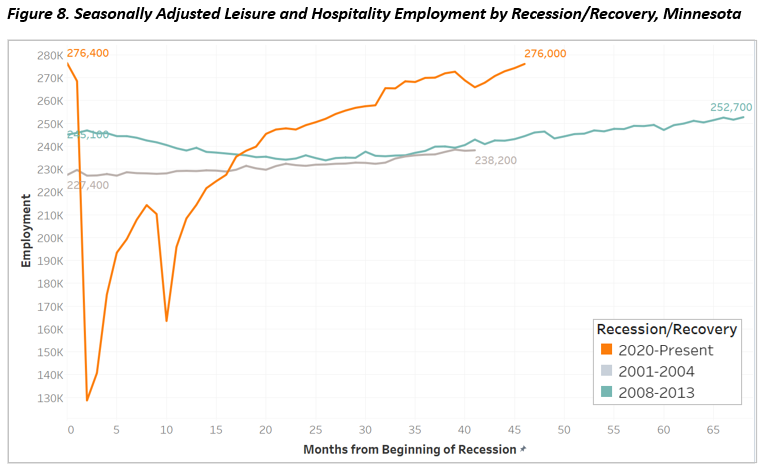

Leisure & Hospitality is another supersector that was heavily affected by the Pandemic Recession, with employment cut in half from February 2020 to April 2020, a loss of 147,700 jobs. Due to the direct impact of the pandemic, Leisure & Hospitality saw a second drop in November 2020, and has seen a slower recovery in the past two years. In addition to new business models and changing consumer preferences, the industry has also struggled with a labor shortage – having more available jobs than available workers to fill them. Even with these headwinds, the sector added over 28,000 jobs (+11.4%) over the last two years, far surpassing growth rates of the previous recoveries (see Figure 8).

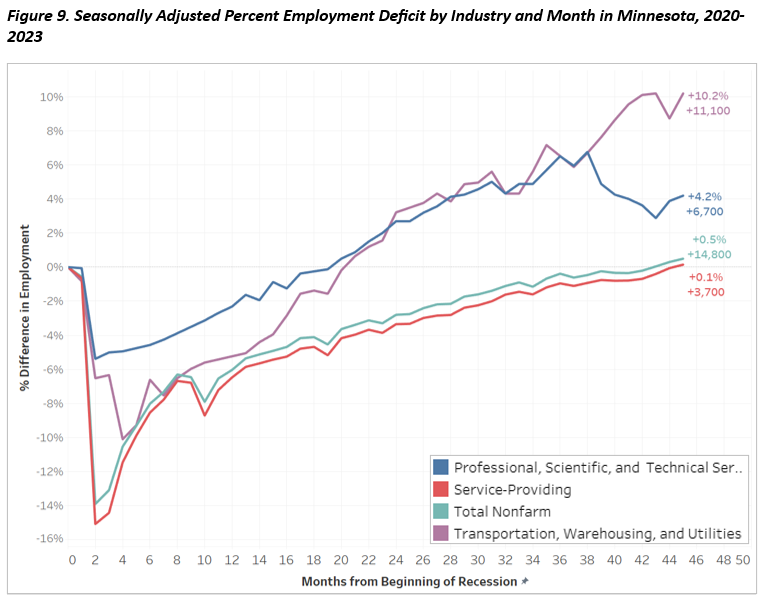

A few more service-providing sectors stood out either because they diverged from the employment trends of the overall domain in the current period or from trends of the past two recessions. Professional, Scientific & Technical Services and Transportation, Warehousing & Utilities fall into the former category. Both outperformed other service-providing sectors throughout the Pandemic Recession and recovery. Each reached pre-pandemic employment in less than half the time it took for total employment to reach that target (see Figure 9). These two sectors benefited from their close connections to goods-producing sectors like Construction as well as changing preferences and practices in e-commerce and shipping.

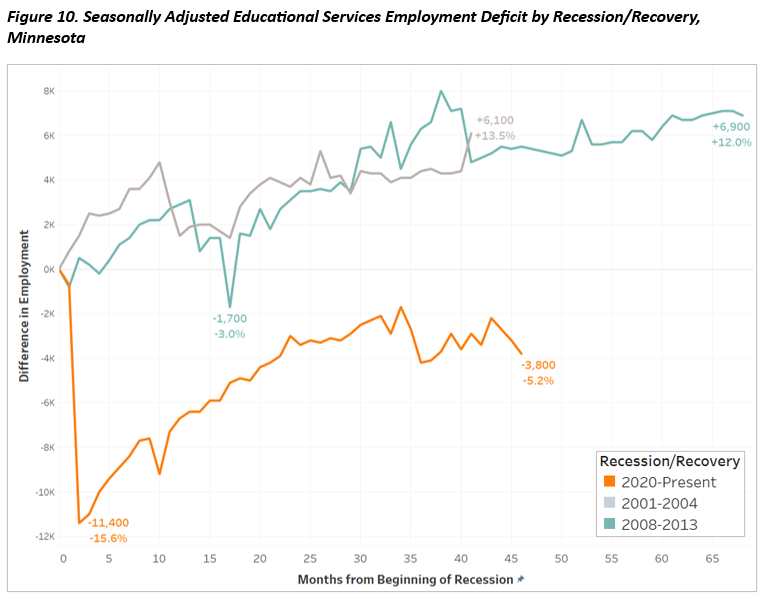

Two final sectors with employment trends that diverged from the previous two recessions and recoveries are Financial Activities and Educational Services. Educational Services experienced an initial percent employment decline in line with service-providing industries, but the recovery since then has been less robust. During the dot-com and Great Recessions, Educational Services largely fared quite well, only dipping into negative territory twice in the Great Recession and not at all in the early 2000s (see Figure 10). Throughout the Pandemic Recession the sector has been at least 2.3% below pre-pandemic levels and remained more than 5% and 3,800 jobs under as of the end of 2023.

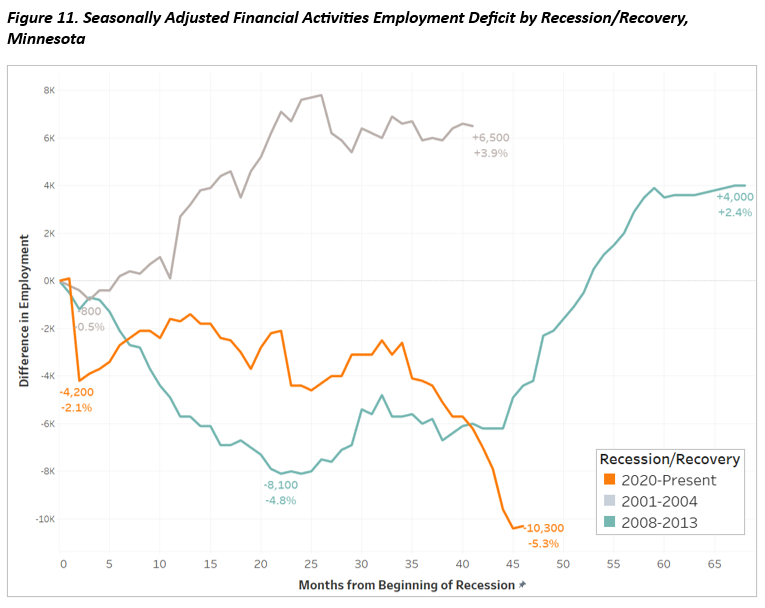

Financial Activities saw a much smaller initial decline than most service-providing industries in the Pandemic Recession, but then continued to lose employment as other sectors started their recoveries. Over the last year, employment in the sector fell 4% and remains more than 5% below where it was in February 2020. Financial Activities also saw sizeable job losses during the Great Recession, but by this point had started its eventual recovery to pre-recession employment levels (see Figure 11).

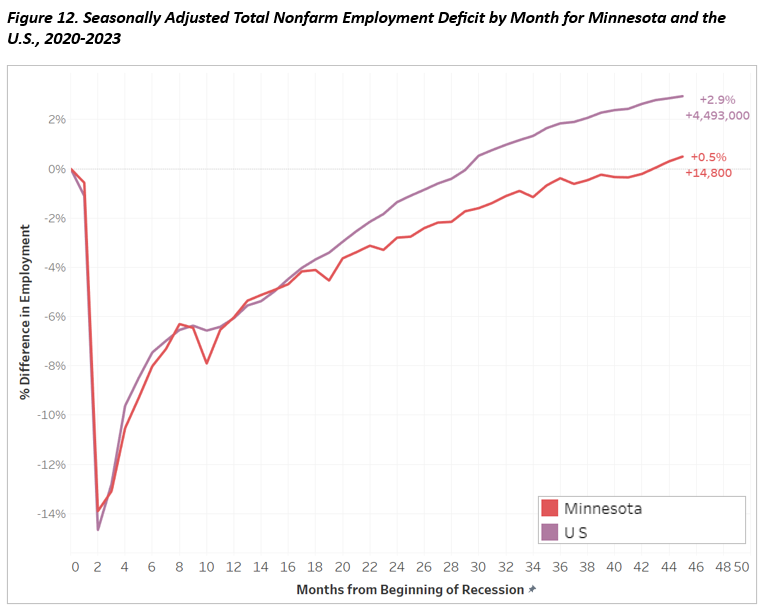

Compared to the rest of the nation, Minnesota's initial employment loss in the Pandemic Recession was slightly less severe. The U.S. bottomed out in April 2020 at –14.7% relative to February whereas Minnesota employment fell 13.9%. Through mid-2021 the two recoveries tracked very closely, but then began to diverge (see Figure 12). U.S. employment growth from that point accelerated faster and surpassed pre-recession employment levels after 30 months. The annual growth rate into August 2022 was 4.4% for the U.S. compared to 2.6% for Minnesota. Minnesota's slower rate of recovery meant an additional 13 months were required to hit that same milestone.

The employment recovery in Minnesota diverged from the U.S. in a few key sectors. While both goods-producing and service-providing employment growth slowed relative to the nation in mid-2021, the goods-producing gap gradually closed while the service-providing gap remained and widened through the end of 2023. Educational Services and Finance & Insurance were the two sectors with the largest relative gaps. By December 2023, U.S. Educational Services employment was 5.1% higher than in early 2020, while at the state level it was 4.4% lower. Similarly, national Finance & Insurance employment was up 2.9%, but down 5.5% in Minnesota by the end of 2023. Minnesota's Construction sector largely outperformed the sector at the national level, while Minnesota Manufacturing and Leisure & Hospitality generally tracked their national counterparts.

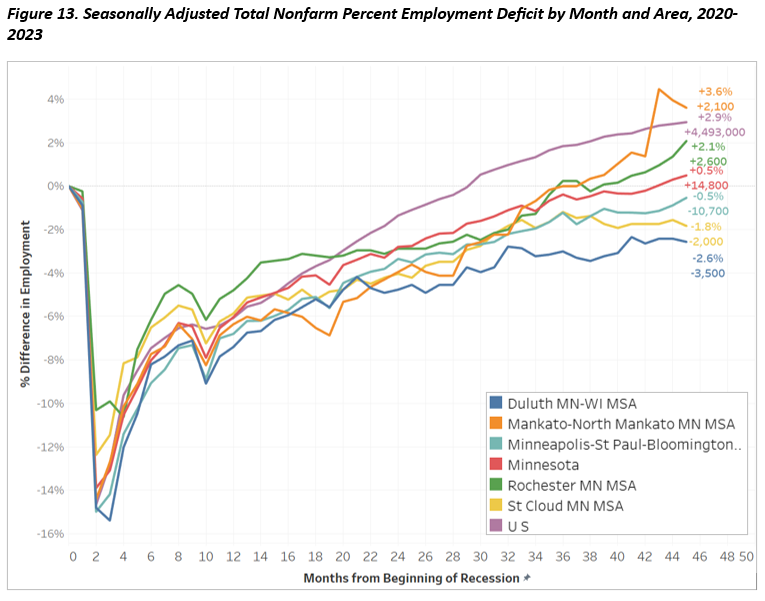

There are five metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) headquartered in Minnesota, led by the Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington MSA, which is also more broadly known as the Twin Cities. With just over 2 million jobs in February 2020, the Twin Cities account for nearly two-thirds of total employment in Minnesota and is easily the largest metro area in the state. As the economic engine, the Twin Cities has typically outperformed the rest of the state in both recessions and recoveries. However, with a high concentration of employment in industries that have not fully recovered, the Twin Cities is still lagging its pre-pandemic employment levels. As of December 2023, the region remained about 11,000 jobs (-0.5%) below the pre-pandemic numbers (see Figure 13).

In contrast, despite the high concentration of employment in Health Care & Social Assistance, the Rochester metro area was the first area in the state to surpass pre-pandemic employment levels and has continued growing faster than the state over the past year as well, growing 4.1% and adding 5,100 jobs. In addition to a well-known Health Care cluster, Rochester also has a huge Manufacturing base and has seen a faster recovery in Leisure & Hospitality than other areas and the state as a whole.

Likewise, the Mankato-North Mankato MSA has seen rapid growth over the past couple years and has surged past its pre-pandemic employment level. As of the end of 2023, the Mankato metro had 2,100 more jobs than before the pandemic, good enough for the largest percent increase (+3.6%) across the five metros. Job growth was strong but would have been stronger if employers could find more workers, as demonstrated by the fact that for a couple months in late 2022, the Mankato-North Mankato MSA reported the lowest unemployment rate of any MSA in the entire U.S.!

With an economy more concentrated in the service-providing domain, including Health Care & Social Assistance and Leisure & Hospitality, the Duluth-Superior MSA remains the furthest behind their pre-pandemic level. At last count, Duluth metro employment was 2.6% or 3,500 jobs under February 2020 levels. Interestingly, this has been the case following all three recessions, with Duluth always below pre-recession employment levels even when the rest of the state was back to breakeven.

Finally, the St. Cloud MSA has followed the overall state trend. Employment in the goods-producing domain is up compared to 2020, but service-providing employment is still down. And whereas the state workforce grew 1.7% over the past year, the St. Cloud MSA saw much slower growth in labor force size (+0.1%, +100). As a result, the St. Cloud metro remained 2,000 jobs ( -1.8%) below pre-pandemic employment measures through December 2023.

The Pandemic Recession and subsequent employment recovery are without comparison in our modern economy. As the 13 charts above show, not all industries and places experienced similar outcomes. Whether jobs were gained or lost and at what magnitude was often a question determined by the type of activity being performed. If an area had a higher concentration of the service-providing industries that were hit the hardest, it was more likely to have a lingering employment deficit. Conversely, if an area had more jobs in the less-affected goods-producing industries, it was more likely to fare better. Even this description borders on oversimplification and for many places the employment recovery remains ongoing amid an historically tight labor market.

Check out our Comparing Recoveries tool if you would like to explore more areas and industries.